1. Introduction

In EP, the relativizer queoccurs in restrictive subject (1a), object (1b) and prepositional (2a, b) relative clauses as well as in all types of appositive relative clauses (3a, b).1

- (1)

- Cordial-Sin, Alcochete (ASCRP)

- a.

- Havia

- there.was

- uma

- a

- azenha

- watermill

- que

- REL

- tinha

- had

- duas

- two

- rodas.

- wheels

- ‘There was a watermill that had two wheels.’

- b.

- A

- the

- comida

- food

- que

- REL

- se

- REFL

- fazia

- made

- antigamente,

- formerly,

- que

- REL

- se

- REFL

- dava

- gave

- para

- to

- os

- the

- porcos

- pigs

- era:…

- was

- ‘The food that was made formerly and that was given to the pigs was the following: …’

- (2)

- a.

- Brito & Duarte (2003: 663)

- O

- the

- cão

- dog

- a

- to

- que

- REL

- fizeste

- you.did

- festas

- caresses

- fugiu.

- fled

- ‘The dog that you caressed fled.’

- b.

- Veloso (2013: 2082)

- O

- the

- país

- country

- em

- in

- que

- REL

- eu

- I

- vivi

- lived

- mais

- more

- tempo

- time

- foi

- was

- o

- the

- Japão.

- Japan

- ‘The country in which I lived most time was Japan.’

- (3)

- a.

- Veloso (2013: 2082)

- A

- the

- Ana,

- Ana

- que

- REL

- está

- is

- sempre

- always

- a

- to

- chatear-me

- annoy-me

- não

- not

- me

- me

- escreve.

- writes

- ‘Ana, who always annoys me, doesn’t write me.’

- b.

- Cordial-Sin, Castro Laboreiro (ASCRP)

- Eu

- I

- tenho

- have

- o

- the

- meu

- my

- neto,

- nephew

- um

- a

- futuro

- future

- advogado,

- lawyer

- que

- REL

- está

- is

- na

- in.the

- universidade.

- university

- ‘I have my nephew, a future lawyer, who studies at the university.’

Only in a subset of these contexts, relative que can be substituted by the relative pronoun o qual. This is the case for restrictive prepositional (including indirect object) relatives (2’a–b) and all appositive relatives (3’a–b).

| (2’) | a. | O cão ao qual fizeste festas fugiu. |

| b. | O país no qual eu vivi mais tempo foi o Japão. |

| (3’) | a. | A Ana, a qual está sempre a chatear-me, não me escreve. |

| b. | Eu tenho o meu neto, um futuro advogado, o qual está na universidade. |

With human antecedents, que can be replaced by quem when it is preceded by a preposition (e.g. 2’’).2

- (2’’)

- A

- the

- pessoa

- person

- com

- with

- quem

- REL

- /

- /

- com

- with

- que

- REL

- o

- the

- professor

- professor

- conversou.

- talked

- ‘The person to whom the professor talked.’

In contrast, que is the only relativizer in restrictive subject and object relatives (1’a–b).

| (1’) | a. | *Havia uma azenha a qual tinha duas rodas. |

| b. | *A comida a qual se fazia antigamente, |

Given these differences in distribution, Brito (1991) proposes that relative que in restrictive subject and object relative clauses has to be analysed as a complementizer, whereas in the contexts in which it can be replaced by o qual, it behaves like a (pro)nominal element. This analysis is based on the classical distinction between relative complementizers and relative (wh-)pronouns, which goes back to Kayne (1975) and Klima (1964). However, more recently, it has been argued that the empirical evidence underlying the distinction between relative complementizers and relative pronouns is not reliable (cf. Poletto & Sanfelici submitted, among others). In addition, a number of recent studies discussing the categorial status of relativizers have proposed a unified analysis of relativizers as functional categories of the type determiner (D) (cf. Kato & Nunes 2009; Kayne 2010; Manzini & Savoia 2002). We will refer to these analyses as the Determiner Hypothesis of Relativizers (DHR).

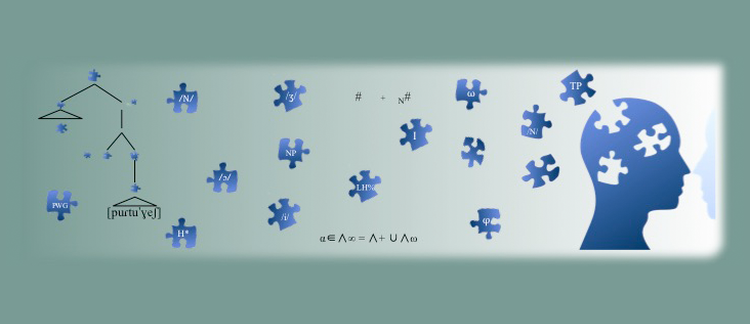

This paper contributes to the ongoing debate regarding the categorial status of relativizers by extending the DHR to the analysis of the European Portuguese relativizer que. In particular, we will discuss a) the status of the relativizer que in restrictive subject and object relatives as opposed to prepositional and appositive relatives, b) the impact of an analysis of que as a D-element for the derivation of the relative clause (raising versus matching versus modification), and c) the attachment of the relative clause in the DP containing the head noun. The paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we show, on the basis of existing proposals in the literature, that the classical distinction between relative complementizers and relative pronouns cannot be maintained and provide the main arguments in favour of extending the DHR to EP relative que. In section 3, we illustrate how the differences between restrictive subject and object relatives on the one hand and restrictive prepositional and appositive relative clauses on the other hand can be captured on the basis of the assumption that que can either be a transitive or an intransitive (demonstrative) determiner. We also discuss the implications for the internal syntactic analysis of relative clauses and the attachment of relative clauses in the DP spine, arguing in favour of a modification analysis for relative clauses in EP. Section 4 summarizes and concludes.

2. The categorial status of relativizers

2.1. Against the dichotomy of relative complementizers and relative (wh-)pronouns

Since Klima (1964), the classical distinction between relative pronouns (wh-pronouns) and relative complementizers has been a matter of discussion (cf. also Kayne 1975; Radford 1981; 2004). According to this distinction, relative (wh-)pronouns behave differently from relative complementizers with respect to the following properties:

| (4) | a. | Pronominals inflect for number and/or case, complementizers do not. |

| b. | Pronominals can be selected by prepositions, complementizers cannot. | |

| c. | Pronominals are sensitive to animacy, complementizers are not. |

In this spirit, Kayne (1975) states explicitly that relative que in French as in (5a) is the same element as in a complement clause (5b), namely “merely a kind of clause introducer” (Kayne 1975: 6f–7, footnote 9):

- (5)

- a.

- Les

- the

- livres

- books

- de

- of

- J.-P.,

- J.-P.

- qu’elle

- REL’she

- lira

- will.read

- tous,

- all

- sont

- are

- três

- very

- bons.

- good

- ‘J.-P.’s books, that she will all read, are very good.’

- b.

- Je

- I

- sais

- know

- que

- that

- Jean

- Jean

- est

- is

- là.

- there

- ‘I know that Jean is there.’

As already mentioned in section 1, Brito (1991) extends this analysis to European Portuguese que in order to account for the distribution of the relativizer in restrictive subject and object relative clauses, where it cannot be replaced by neither o qual nor by quem.

According to Brito (1991), all types of relative clauses occupy an adjunct position. Hence, neither type of relative que can be a genuine nominal since such a relativizer would turn the whole relative clause into a nominal itself and this would violate the Case filter. In contexts where que is interchangeable with more complex relative pronouns like o qual, the relativizer is nominal but corresponds to a nominal without φ-features. It is base generated in argument position within the relative clause, and then moved upwards to the C-domain of the relative clause. In restrictive subject and object relative clauses, where que cannot be replaced by o qual, que is a complementizer. The operator-variable relation is established by a silent operator, which is base generated in argument position and then rises to the specifier of CP. Finally, at LF, the complementizer-like que enters the chain of antecedent and variable by being co-indexed with the silent operator.

Brito’s (1991) analysis already cuts across the traditional distinction between relative pronouns and relative complementizers presented in (4) insofar as the author distinguishes between relative pronouns with and without φ-features (quem vs. o qual/que in prepositional/appositive contexts). In fact, it cannot be taken for granted that pronouns always overtly show number and/or case agreement. For example, numerals as well as exclamative and interrogative determiners also do not (always) show agreement morphology.3 The same is true for animacy distinctions. Although complementizers, unlike pronouns, generally do not show animacy distinctions, this does not automatically imply that all pronominal elements are marked for being [+/–animate]. As for the preposition constraint, it is questionable whether this test can be applied to subject and object relative clauses because subjects and direct objects do not occur with prepositions in EP.

Poletto & Sanfelici (submitted) question the strict dichotomy of complementizers and pronouns overall. On the basis of Italian varieties, the authors show that there exist agreeing complementizers and non-agreeing pronouns like il quale. One example for agreeing complementizers is Marebbano, a variety spoken in the Val Badia, whose relativizer system is specified for case and for deixis: a relativizer whose form is identical to the complementizer in complement clauses, che, is selected as a default (6a, b). Only in a very specific subset of subject extraction does a different lexeme, co, occur, namely in third person singular and plural, in restrictive as well as non-restrictive relatives (6c, d). In first and second person, on the other hand, che plus a subject clitic is selected (6e):

- (6)

- Poletto & Sanfelici (submitted)

- a.

- I

- the

- jogn

- boy

- dij

- says

- ch’al

- that.SBJCL.3SG

- mangia

- eats

- massa

- too.much

- ćern.

- meat

- ‘The boy says that he eats too much meat.’

- b.

- La

- the

- ëra

- lady

- che

- REL

- te

- SBJCL.2SG

- ás

- has

- encunté

- met

- ennier

- yesterday

- ćianta

- sings

- pal

- for.the

- cor.

- chorus

- ‘The lady you met yesterday sings in the chorus.’

- c.

- I

- the

- jogn

- boys

- co

- REL

- laora a Milan va vigne dé

- work in Milan go every day

- con la ferata.

- with the train

- ‘The boys that work in Milan take the train every day.’

- d.

- La

- the

- Talia,

- Italy

- co

- REL

- à

- has

- les

- the

- leges

- laws

- dër

- very

- rigoroses,

- rigorous

- prodüj

- produces

- le

- the

- miù

- best

- ere

- oil

- d’orì.

- of’olive

- ‘Italy, that has very strict laws, produces the best olive oil.’

- e.

- Tö,

- you

- che

- REL

- te

- SBJCL.2SG

- manges

- you.eat

- vigne

- each

- dé

- day

- ćern,

- meat

- cumpres

- you.buy

- püćia

- less

- ordöra.

- vegetable

- ‘You, who eat meat every day, buy few vegetables.’

In contrast, quale, which is a pronominal element, does not show agreement features. In Old Neapolitan, quale shows neither case nor person nor number distinctions, just as in the modern Italian varieties. In contrast to the latter, however, Old Neapolitan quale can occur bare, without a definite article (7):

- (7)

- Poletto & Sanfelici (submitted)

- Haverno

- they.have

- facte

- done

- cose

- things

- quale

- REL

- mai

- never

- tenarono

- they.tried

- fare.

- to.do

- ‘They did things that they never tried to do.’

Poletto & Sanfelici (submitted) argue on the basis of these observations that relativizers cannot be split into non-inflecting complementizers and inflecting pronouns.4

In the next section, we turn our attention to the Determiner Hypothesis of Relativizers (DHR).

2.2. The Determiner Hypothesis of Relativizers

Although the relativizer que is superficially identical with a complementizer in synchrony, it often shares a common diachronic source with demonstratives, determiners or interrogative elements. Cohen (1990), who investigates the diachronic development of EP relative que, sees no evidence that relative que, which arguably stems from the Latin interrogative/relative paradigms, has “lost its anaphoric character [and has been] reinterpreted or reanalyzed as a link word or a complementizer” (Cohen 1990: 99).

Several authors explicitly argue in favour of an analysis of relative elements in terms of determiners. Manzini & Savoia (2002) assume for Italian that-complementizers, transitive and intransitive interrogatives as well as relative che that they constitute the same kind of element, a transitive determiner. The authors argue that all these elements bind a variable, either a propositional or a nominal one (see 8). In (8a–b), interrogative che binds the internal argument of a verbal or a nominal predicate, while complementizer che binds a variable with sentential content in (8c).

| (8) | Manzini & Savoia (2002) | |||||||

| a. | Che | fai? | [che x [fai (x)]] | |||||

| che | you.do | |||||||

| ‘What are you doing?’ | ||||||||

| b. | Che | camicia | hanno | portato? | [che x [camicia (x)]] | |||

| che | shirt | they.have | worn | |||||

| ‘What shirt did they wear?’ | ||||||||

| c. | Mi | hanno | detto | che | vieni | domani. | [che x [x: vieni domani]] | |

| me | they.have | said | che | you.come | tomorrow | |||

| ‘They told me that you will come tomorrow.’ | ||||||||

| d. | Sono | quelli | che | chiamo | sempre. | |||

| they.are | those | che | I.call | always | ||||

| ‘They are the ones that I always call.’ | ||||||||

The authors argue that (8d) can be analysed in a parallel fashion. They assume that the relativizer che introduces a propositional variable as in declaratives, while the head binds the argumental variable.5

Kayne (2010) himself challenges his original proposal and argues for English that that the usually assumed differences between that in relative clauses and relative pronouns like who/which are not as crucial, as all can be put down to characteristics of that being a demonstrative/determiner whose NP has risen. He argues that relative that is less different from other relative pronouns like which as it seems at first sight because, among other things, both cannot occur as a possessor in constructions like (9).

| (9) | Kayne (2010) | |

| a. | *the book which’s first chapter is so well known | |

| b. | *the person that’s book we were talking about | |

Kayne (2010: 194) argues that the ungrammaticality of (9b) is not a result of that being a complementizer but results from the fact that intransitive demonstratives in general cannot occur as possessors (*That’s importance is undeniable similar to *This’s importance it undeniable; in opposition to The importance of that is undeniable). According to Kayne (2010), the insensitivity of that with respect to animacy also results from its categorial status as a demonstrative. English demonstrative that is indifferent to humanness with an overt NP (that house/insect/person), but incompatible with a [+human] interpretation, when the NP is silent (*That thinks too much.).6 In appositive relative clauses, that cannot refer to a [+human] referent (10a), but is (marginally) compatible with [–human] reference (10b).

| (10) | Kayne (2010) | |

| a. | *Your oldest friend, that I’ve been meaning to talk to. | |

| b. | Your last paper, *(?that) I’ve been meaning to reread. | |

Hence, there are contexts in which that is in fact sensitive to the [+/–human] distinction. Kayne (2010) concludes that relative that is some kind of demonstrative that. He draws a parallelism between English that and Romance que/che:

| (11) | Kayne (2010) | |||

| a. | that | book | ||

| b. | Che | bel | libro! | |

| what | beautiful | book | ||

| ‘What a beautiful book!’ | ||||

Kato & Nunes (2009) pursue a determiner analysis of the relativizer que in Brazilian Portuguese and argue against an analysis of que in terms of a complementizer. Assuming a raising analysis for restrictive relatives, Kato & Nunes (2009) argue that a complementizer analysis of que would imply “that the launching position of the movement is an NP gap” (Kato & Nunes 2009: 95). This, however, would be at odds with the unacceptability of sentences in which an NP occupies an argument position such as *Bill saw picture (cf. also Borsley 1997).

Bianchi (1999) circumvents this problem by assuming that the relative gap in that-relatives involves a DPrel with an empty relative determiner. This DP adjoins to the CP involving the relative complementizer. From there, the empty determiner is extracted and adjoins to the determiner head of the DP including the relative clause. This analysis correctly excludes an NP gap in argument position, but it also makes a number of non-standard assumptions concerning the structure of the DP. For example, it would be incompatible with the general assumption that in Portuguese, as in all Romance languages, determiners are either moved to SpecDP (e.g., demonstratives) or merged in D°.

Kato & Nunes (2009) propose for BP relative que that it is a determiner which embeds the head noun in a parallel fashion as interrogative determiners do ([DP que quadro]). They argue that the relativizer has to have argument-status because an argument is required inside subject and object relative clauses (a DP constituent).7 Like Kayne (2010) for Italian, Kato & Nunes (2009) also point to the parallelism of que with exclamative and interrogative determiners in Brazilian Portuguese.

- (12)

- Kato & Nunes (2009)

- a.

- Que

- which

- livro

- book

- compraste?

- you.bought

- ‘Which book did you buy?’

- b.

- Que

- what

- coisa!

- thing

- ‘Gee!’

2.3. Extending the DHR to EP relative que

The arguments given in section 2.1 and 2.2 in favour of the DHR can easily be transferred to the relativizer que in European Portuguese.

First, as we have seen, the fact that que does not (overtly) inflect for number or case and does not show animacy distinctions does not necessarily speak in favour of an analysis of que as a complementizer. On the one hand, complementizers can show agreement marking (so-called inflected complementizers, see section 2.1), and on the other hand, pronominal elements and determiners do not always show overt agreement morphology. In addition, if we follow the view that que is a determiner-like element, the test regarding sensitivity to animacy loses its illuminating character, as determiners like articles o, uma (‘themasc.’, ‘afem.’) or demonstratives este, aquela (‘thismasc.’, ‘thatfem.’) do not discriminate between animate and inanimate complements either. Furthermore, it is not entirely true that relative que is insensitive to the (in)animacy of its antecedent in all contexts. According to Veloso (2013), in prepositional contexts, quem is preferred for human head nouns. Hence, (13a) is slightly better than (13b). With an inanimate head noun, que would be the preferred option in the same context.

- (13)

- Veloso (2013: 2083)

- a.

- O

- the

- idiota

- idiot

- a

- to

- quem

- REL

- emprestei

- I.lent

- esse

- that

- livro…

- book

- b.

- O

- the

- idiota

- idiot

- a

- to

- que

- REL

- emprestei

- I.lent

- esse

- that

- livro…

- book

- both: ‘The idiot to whom I lent that book…’

In this sense, EP que behaves in a similar fashion to English that, as shown by Kayne (2010; cf. 2.2): in some contexts, the relativizer is sensitive to animacy, which implies that que can surface as quem if it carries a [+human] feature (Kato & Nunes 2009).

Second, the diachrony of que also speaks in favour of a parallelism with interrogative que and against its analysis as a complementizer. Whereas relative and interrogative que in EP have the same diachronic origin, the declarative complementizer que has a different diachronic source. Classical Latin had a partially overlapping system of interrogative and relative pronouns, which already in Vulgar Latin developed into a system without formal distinctions between interrogative vs. relative, feminine vs. masculine and singular vs. plural (Cohen 1990; Mattos e Silva 1993).

“The elimination of the categories Case, Gender and Number which took place in the Relative/Interrogative pronoun system in the evolution from VL to Portuguese led the QUE to be interpreted as an unmarked form, a merging of forms that were contrastive in Latin. QUE is the Portuguese primary Relative pronoun, independent of its double origin, Subject QUE having originated from the Nom., QUI and QUE in other syntactic functions from the Accusative.” (Cohen 1990: 122f)

According to Cohen (1990), que as a subject relative pronoun derives from the Latin interrogative Quis (NOM, SG, M/F) and the Latin relativizer Quī (NOM, S/PL, M), which merged into the same form interrogative/relative Qui (NOM, S/PL, M/F) already in Vulgar Latin. In all other functions, que has originated from accusative Que(m) (ACC, S/PL, M/F) (cf. also Lausberg 1972). In the earliest Old Portuguese documents from the 12th/13th centuries, que is the only form attested. Declarative que, also a conflation of different forms, has a different source: the Vulgar Latin conjunctions quod and qui(a) as well as interrogative/relative quid. Formally, que can be phonologically derived from qui(a) and quid. The fact that relative que and declarative que originate from different sources makes it plausible to assume that both elements always belonged to different categories despite their formal identity nowadays.8

Third, coming back to the synchronic similarities between interrogative and relative que, we assume that both move to the left periphery in order to check information structure-related features.9 With respect to interrogative que, it can be assumed that it has to check a [+wh] (Rizzi 1990; 1996) or [+interrogative] feature or – because interrogatives ask for information not given in the context and relate to the introduction of new information – a [+focus] feature. In Rizzi’s (1997; 2004) split-CP framework of the left periphery, this position would be identified with FocP. With respect to relative que, we assume in line with Bianchi (1999: 191) that movement of the relative DP is triggered by a [+topic] feature.

It is a well-known fact from language acquisition and language processing that subject-relatives are strongly preferred over object relatives (Costa, Lobo & Silva 2010; Friedmann, Belletti & Rizzi 2009; among others). Given the fact that subjects are more likely to be topics than objects, this observation may be interpreted as evidence for the assumption that the relativizer typically refers to previously given information and is therefore related to a topic interpretation.

In our corpus study (cf. Barbosa (coord.) n.d., Rinke coord., Martins (coord.) 2000-), this subject-object asymmetry is also confirmed: the head noun represents a constituent that is typically associated with new information, whereas the relativizer is a subject constituent in most of the cases. But also in the cases in which relative que represents the object of the relative clause, it still represents the aboutness topic. Out of a total of 1549 headed relative clauses, the antecedent is clearly a discourse-new element in 69% of the cases: the object (in canonical object position) in 341 cases (22%), the complement of a presentational verb in 680 cases (44%) and a postverbal subject in 49 cases (3%). The relativizer que, on the other hand, represents the subject in 954 examples (62%), which typically coincides with discourse-old or topical information. (14a, b) represent prototypical examples from the corpus:

- (14)

- Cordial-Sin, Alcochete (ASCRP)

- a.

- É

- is

- um

- a

- carneiro

- mutton

- que

- REL

- já

- already

- está

- is

- capado.

- castrated

- ‘It is a mutton that is already castrated.’

- b.

- Isto

- this

- era

- was

- uma

- a

- terra

- land

- que

- REL

- dá

- gives

- produto.

- product

- ‘This was a fertile land.’

In (14a, b) the head noun is an indefinite DP complement of a presentational clause. The relative pronoun que refers back to this constituent and functions as the aboutness topic of the relative clause, i.e., the rest of the relative clause is a comment about the entity represented by que.

Fourth, que not only shows similarities with interrogative pronouns/determiners, but also exhibits similarities with demonstratives, a perspective which was also argued for by Kayne (2010) with respect to the English relativizer that. Kato & Nunes (2009) argue that post-nominal demonstratives show similar behaviour as relativizers in Brazilian Portuguese. According to the authors, the demonstrative determiner este (‘this’) in (15a) triggers obligatory overt movement of the noun livro (‘book’) in a parallel fashion to relative determiners like que (in a raising perspective).10 They assume that in such contexts, demonstrative determiners can be used as “relative pronouns of sorts” (Kato & Nunes 2009: 97). (15b) shows that this structure is also possible in EP.

- (15)

- a.

- Kato & Nunes (2009: 97)

- Ele

- he

- sempre

- always

- cita

- cites

- um

- a

- livro,

- book,

- livro

- book

- este

- this

- que

- REL

- na

- in.the

- verdade

- reality

- não

- not

- existe.

- exists

- ‘He always cites a book which in reality does not exist.’

- b.

- Veloso (2013: 2082)

- O

- the

- constituinte

- constituent

- relativo

- relative

- que

- REL

- contém

- contains

- que

- que

- (constituinte

- (constituent

- esse,

- this,

- como

- as

- se

- REFL

- viu,

- saw

- que

- REL

- pode

- can

- consistir

- consist

- unicamente

- only

- no

- in.the

- pronome)

- pronoun

- é

- is

- aquele

- that.DEM

- que

- REL

- aceita

- accepts

- maior

- bigger

- diversidade

- diversity

- de

- of

- contextos

- contexts

- no

- in.the

- que

- REL

- respeita

- concerns

- à

- to.the

- sua

- its

- função

- function

- dentro

- inside

- da

- of.the

- oração

- clause

- relativa.

- relative

- ‘The relative constituent which contains que (and which – as we have seen – can only consist of a pronoun) is the one that accepts a greater diversity of contexts concerning its function in the relative clause.’

Fifth, it has been noted that demonstratives have an influence on the interpretation of a relative clause, if the two are combined in a noun phrase. In particular, in a noun phrase containing a demonstrative determiner, a relative clause cannot be interpreted as restrictive. Restrictive relative clauses contribute to the identification of the referent by restricting the scope of the head noun. The interpretation of a noun phrase modified by a restrictive relative clause can be described as an intersection of the set denoted by the restrictive relative clause and the set denoted by the head noun (Larson & Segal 1995: 256; Partee 1975: 229).

The incompatibility of demonstratives and restrictive relative clauses can be illustrated on the basis of anaphoric resolution. Fabricius-Hansen (2009; 2015) argues that a modifier is non-restrictive in a given context if anaphoric resolution yields the same result for the modified DP as well as for its unmodified counterpart. If anaphoric resolution yields a different result for the modified and the non-modified DP, the modifier is restrictive. With respect to the incompatibility of demonstratives with restrictive relative clauses, the following examples show that the relative clause cannot be interpreted as restrictive in the given context if the respective noun phrase is introduced by a demonstrative.

- (16)

- Context: In 2012, 200 candidates applied for the job.

- a.

- A

- the

- comissão

- commission

- convidou

- invited

- {estes

- these

- candidatos}

- candidates

- ={-os}

- =-them

- para

- for

- um

- a

- workshop

- workshop

- (#mas

- #but

- não

- not

- todos

- all

- os

- the

- candidatos).

- candidates

- ‘The commission invited {these candidates} = them for a workshop (#but not all candidates).’

- b.

- {A

- the

- comissão

- commission

- convidou

- invited

- {estes

- these

- candidatos,

- candidates

- que

- REL

- eram de Portugal}

- were of Portugal

- ={-os}

- =them

- para

- for

- um

- a

- workshop

- workshop

- (#mas

- #but

- não

- not

- todos

- all

- os

- the

- candidatos).

- candidates

- ‘The commission invited {these candidates, which were from Portugal,} = {them} for a workshop (#but not all candidates).’

- c.

- {A

- the

- comissão

- commission

- convidou

- invited

- {os

- the

- candidatos

- candidates

- que

- REL

- eram de Portugal}

- were of Portugal

- ≠{-os}

- ≠them

- para

- for

- um

- a

- workshop

- workshop

- (OK:

- OK:

- mas

- but

- não

- not

- todos

- all

- os

- the

- candidatos).

- candidates

- ‘The commission invited {the candidates that were from Portugal} ≠ {them} for a workshop (OK: but not all candidates).’

In the context given in example (16), anaphoric resolution necessarily leads to the same result for the non-modified (16a) and the DP modified by a relative clause (16b). In (16c), where the noun phrase is modified by a relative clause and introduced by a definite article, anaphoric resolution may yield a different result for the modified and the non-modified DP (subset relation). Hence, in the presence of a demonstrative determiner that establishes referentiality (16b), anaphoric resolution yields the same result for the modified DP as well as for its unmodified counterpart. In these cases, the relative clause cannot be interpreted as being restrictive.

This can also be shown on the basis of examples like (17a–b). In general, restrictive relative clauses can both occur in the indicative and in the subjunctive mood, whereas appositive relative clauses are incompatible with a subjunctive. The examples show that, as soon as the head noun combines with a demonstrative, a subjunctive is excluded.

- (17)

- a.

- Procuro

- I.look.for

- uma

- a

- secretária

- secretary

- que

- REL

- saiba

- knows.SUBJ.

- inglês.

- English

- ‘I’m looking for a secretary that should know English.’

- b.

- Procuro

- I.look.for

- uma

- a

- secretária

- secretary

- que

- REL

- sabe

- knows.IND

- inglês.

- English

- ‘I’m looking for a secretary that knows English.’

- c.

- *Procuro

- I.look.for

- esta

- this

- secretária

- secretary

- que

- REL

- saiba

- knows.SUBJ

- inglês.

- English.

Demonstratives and restrictive relative clauses seem to share common features as can also be illustrated on the basis of the following observation: both demonstratives and restrictive relative clauses are incompatible with a generic interpretation. In the examples (18b, c), the sentence cannot refer to cats as a kind (in contrast to 18a) as it would be required in the case of a generic interpretation.

- (18)

- a.

- Os

- the

- gatos

- cats

- gostam

- like

- de

- of

- leite.

- milk

- ‘Cats like milk.’

- b.

- Estes

- these

- gatos

- cats

- gostam

- like

- de

- of

- leite.

- milk

- ‘These cats like milk.’

- c.

- Os

- the

- gatos

- cats

- que

- REL

- vivem

- live

- no

- in.the

- nosso

- our

- jardim

- garden

- gostam

- like

- de

- of

- leite.

- milk

- ‘The cats that live in our garden like milk.’

The incompatibility of demonstratives and restrictive relative clauses within one and the same DP as well as the similar effect they trigger with respect to generic interpretations show that both share common features. This indicates in our view that both are introduced in the same position within the DP spine. Based on the assumption that restrictive relative clauses (in contrast to appositive relative clauses) as well as demonstratives are merged in a low structural position in the DP spine (cf. Alexiadou, Haegeman & Stavrou 2008; Giusti 2002), we propose that demonstratives and restrictive relative clauses compete for the same structural position (possibly SpecnP, cf. section 3.2). We will argue furthermore that the complementary distribution of restrictive relative clauses and demonstratives illustrates that DemP (the projection of the demonstrative) and the CP including relative que share common features. Given the parallelism of que with demonstratives, this comes as no surprise.

It has to be admitted that there are cases in which the demonstrative can be associated with a relative clause that is not clearly appositive. One such case is reported by Kleiber (1987: 75). He argues that so called emphatic relative clauses like (19) are neither clearly appositive nor unequivocally restrictive.

- (19)

- Kleiber (1987: 75)

- Tu

- you

- te

- REFL

- souviens

- remember

- de

- of

- ce

- this

- professeur

- teacher

- qui

- REL

- ne

- not

- donnait

- he.gave

- que

- but

- de

- of

- bonnes

- good

- notes?

- grades

- ‘Do you remember that teacher that only gave good grades?’

According to Birkner (2008: 113), a restrictive interpretation of the relative clause in combination with a demonstrative is possible in spoken registers of German under very special conditions. It depends on a non-deictic and unspecific interpretation of the demonstrative, which then serves as an Unschärfemarkierer, ‘marker of blurredness’, in Birkner’s (2008: 113) terms.

- (20)

- Adapted from Birkner (2008: 113)

- Oder

- or

- kennste

- you.know

- diese

- these

- Typen

- guys

- die

- REL

- auf

- on

- diesem

- this

- Boot

- boat

- immer

- always

- reisen

- they.travel

- da.

- there

- ‘Or do you know the kind of guys that always travel on this kind of boot?’

Crucially, the demonstrative in (19) or (20) does not correspond to the prototypical interpretation of the demonstrative: it has neither an anaphoric nor a deictic interpretation and serves as a kind of discourse marker. In our view, such examples do not represent counterexamples to the general incompatibility of demonstratives and restrictive relative clauses.

The fact that demonstratives can co-occur with appositive relative clauses results from the analysis of appositions: the reason is that appositions are attached at a higher structural level, outside the scope of the external D (cf. Brito 2005: 408). Therefore, they are structurally freer, much in the sense of Cinque’s (2008) “non-integrated non-restrictive” relative clauses, which allow non-adjacency to the head noun and non-identity of the external and the “internal” head, i.e., the relativized element inside the relative clause (cf. chapter 3.1).

3. Transitive and intransitive que

In the previous section, we have argued that relative que shows similarities with demonstratives and interrogatives and has to be analysed as belonging to the category D. However, if we compare relative que to demonstrative and interrogative determiners, an obvious difference arises: in contrast to demonstratives and interrogative que, relative que cannot occur in combination with the head noun:

- (21)

- a.

- Demonstrative:

- Li

- I.read.PST

- este

- this

- livro.

- book

- ‘I read this book.’

- b.

- Interrogative:

- Que

- which

- livro

- book

- leste?

- you.read.PST

- ‘Which book did you read?’

- c.

- Relative:

- *O

- the

- livro

- book

- que

- REL

- livro

- book

- li.

- I.read.PST

One possibility to explain this difference would be to assume that relative que can only appear as an intransitive determiner just like demonstrative este or interrogative que when they occur in isolation. Since que replaces a DP in such contexts and has pronominal properties, this analysis can only be adopted for the contexts in which que is interchangeable with other pronominal relativizers like o qual,11 i.e., in appositive as well as in prepositional restrictive relatives.

3.1. Que as an intransitive determiner in appositive relative clauses and restrictive relative clauses introduced by a preposition

We assume that que in appositive relative clauses as well as in prepositional restrictive relative clauses does not co-occur with a nominal element because it reflects the intransitive use of demonstratives.

For this kind of relativizer, we extend Cinque’s (2008) analysis of Italian il quale in terms of an e-type pronoun. Cinque (2008) departs from the observation that non-restrictive relative clauses in Italian can either be introduced by che/cui or by il quale. He shows that it is only when il quale occurs that the relative clause shows illocutionary independence (22a) and can occur non-adjacent to the head noun (22b):

- (22)

- a.

- L’unico

- the.only

- che

- REL

- potrebbe

- could

- è

- is

- tuo

- your

- padre,

- father

- il

- il

- quale/?*che

- quale/?*che

- potrà,

- could

- credi,

- you.think

- perdonarci

- forgive.us

- per

- for

- quello

- that

- che

- REL

- abbiamo

- we.had

- fatto?

- made

- ‘The only one who could is your father, by whom will we ever be forgiven, you think, for what we have done?’

- b.

- Da

- of.the

- quando

- when

- i

- the

- russi

- Russians

- se

- REFL

- ne

- CL.LOC

- sono

- they.have

- andati,

- gone

- i quali/*che

- i quali/*che

- non

- not

- si

- REFL

- erano

- they.had

- mai

- never

- veramente

- really

- integrati

- integrated

- con

- with

- la

- the

- popolazione,

- population

- la

- the

- pace

- peace

- è

- is

- finita.

- finished

- ‘Since the Russians left, who had never really mixed with the population, there is no more peace.’

Cinque (2008) concludes that non-restrictive relative clauses with il quale are structurally more independent. He distinguishes between “integrated” non-restrictive relative clauses introduced by che/cui and “unintegrated” ones introduced by il quale (cf. 22a and b). As for the il quale-kind of relative pronouns, Cinque (2008: 120) assumes that they are e-type pronouns, that is, pronouns bound in semantics but not in syntax, as they are not c-commanded by their antecedent (cf. Evans 1980). Therefore, he takes them to “behave just like demonstrative pronouns (and adjectives) which can resume an antecedent across discourse” (Cinque 2008: 120; cf. also Jackendoff 1977). According to his analysis, appositive relative clauses are merged above the DP of the head noun, that is, outside the scope of the determiner.

Now, interestingly, EP que is not excluded in these contexts, cf. (23), although it seems to be more natural in (23a) and rather marginal or ungrammatical in (23b).

- (23)

- a.

- O

- the

- único

- only

- que

- REL

- podia

- could

- é

- is

- o

- the

- teu

- your

- pai,

- father

- o qual/que

- o qual/que

- poderá,

- could,

- pensas

- think

- tu,

- you,

- perdoar

- forgive

- aquilo

- that.DEM

- que

- REL

- fizemos?

- we.did

- ‘The only one who could is your father, by whom will we ever be forgiven, you think, for what we have done?’

- b.

- Desde

- from

- que

- that

- os

- the

- russos

- Russians

- se

- REFL

- foram

- they.went

- embora,

- away

- os quais/??,*12

- os quais/??*

- que

- que

- nunca

- never

- se

- REFL

- tinham

- they.had

- realmente

- really

- misturado

- mixed

- com

- with

- a

- the

- populaҫão,

- population

- a

- the

- paz

- peace

- acabou.

- ended

- ‘Since the Russians left, who had never really mixed with the population, there is no more peace.’

Although example (23b) is judged as marginal/ungrammatical by some speakers, it seems to be the case that appositive relative clauses introduced by que can occur non-adjacent to the head noun as in example (14b), repeated here as (24a). An example from our corpus is (24b), where the appositive relative clause with que occurs separated from the head noun.

- (24)

- a.

- Veloso (2013: 2082)

- O

- the

- constituinte

- constituent

- relativo

- relative

- que

- REL

- contém

- contains

- que

- que

- (constituinte

- (constituent

- esse,

- this,

- como

- as

- se

- REFL

- viu,

- saw

- que

- REL

- pode

- can

- consistir

- consist

- unicamente

- only

- no

- in.the

- pronome)

- pronoun

- é

- is

- aquele

- that

- que

- REL

- aceita

- accepts

- maior

- more

- diversidade

- diversity

- de

- of

- contextos

- contexts

- no

- in.the

- que

- which

- respeita

- concerns

- à

- to.the

- sua

- its

- função

- function

- dentro

- inside

- da

- of.the

- oração

- clause

- relativa.

- relative

- ‘The relative constituent which contains que (and which – as we have seen – can only consist of a pronoun) is the one that accepts a greater diversity of contexts concerning its function in the relative clause.’

- b.

- Cordial-Sin, Castro Laboreiro (ASCRP)

- Depois

- after

- fica

- stays

- aquele

- that

- bocadinho

- bit

- de

- of

- cabedal,

- leather

- no

- in.the

- fundo,

- bottom

- que

- REL

- é

- is

- para

- for

- pôr

- to.put

- ali

- there

- a

- the

- pedrinha.

- little.stone

- ‘Afterwards there is that little bit of leather left, at the bottom, which is for putting there the little stone.’

One possible interpretation of these facts is that Portuguese also disposes of two types of non-restrictive relative clauses, but the status of relative que is different to the one of its Italian counterpart che, i.e., it is freer in its distribution. Also the following difference speaks in favour of this idea: Italian che can only occur in prepositionless contexts, that is, in appositive and restrictive subject and object relatives. In structures with prepositions, only a more complex relativizer is possible:

- (25)

- a.

- *La

- the

- ragazza

- girl

- con

- with

- che

- REL

- ho

- I.have

- parlato

- spoken

- ieri.

- yesterday

- b.

- La

- the

- ragazza

- girl

- con

- with

- la

- REL

- quale/cui

- ho

- I.have

- parlato

- spoken

- ieri.

- yesterday

- ‘The girl to which I spoke yesterday.’

As shown above, EP que is freely exchangeable with o qual in restrictive IO- and PP-, as well as in all kinds of appositive relatives. Extending Cinque’s (2008) analysis of il quale in non-integrated appositive relative clauses as an e-type pronoun to EP o qual13 and que in the same context, we may conclude that also the incompatibility of Italian che and the compatibility of EP que with prepositional relative clauses may be explained on the basis of the same cross-linguistic contrast: Portuguese que, but not Italian che, can occur as an intransitive determiner and can have the status of an e-type pronoun. As expected, que occurs in combination with prepositions (26) just like the intransitive demonstrative este (26a).

- (26)

- a.

- Falei

- I.spoke

- [com

- with

- este].

- this

- ‘I talked to this one.’

- b.

- Nunca

- never

- tinha

- I.had

- visto

- seen

- antes

- before

- o

- the

- homem

- man

- [[

- com

- with

- o qual]

- REL

- falei].

- I.spoke

- ‘Never before had I seen the man I talked to.’

- c.

- Nunca

- never

- tinha

- I.had

- visto

- seen

- antes

- before

- o

- the

- homem

- man

- [[

- com

- with

- que]

- REL

- falei].

- I.spoke

- ‘Never before had I seen the man I talked to.’

If que in appositive and prepositional restrictive relative clauses behaves like an intransitive demonstrative and has to be analysed as an e-type pronoun, the question why relative que only occurs in isolation (cf. example 21c) narrows down to restrictive subject and object relative clauses. We will discuss the status of que in these kinds of relative clauses in the next section.

3.2. Que as a transitive determiner in restrictive object and subject relative clauses

According to Kato & Nunes (2009), the reason why que cannot co-occur with the noun phrase in restrictive relative clauses is that it occurs as a transitive determiner whose complement noun has moved out of the DP (raising analysis of relative clauses) (cf. Bianchi 1999; 2000; de Vries 2002; Kato & Nunes 2009; Kayne 1994; Kenedy 2007; Poletto & Sanfelici submitted; among others).

More precisely, Kato & Nunes (2009) assume that the relative determiner que initially forms a DP with the respective head noun ([DP que quadro]). This DP is base generated in argument position within the relative clause and subsequently raised up to the C-domain of the relative clause. In a next step, the head noun raises further. Following Kayne (1994), Kato & Nunes (2009: 96) propose a structure where the target position of the head noun is the DP’s specifier (27a). Another version of raising, proposed by Bianchi (1999: 79), assumes that the head noun moves out of the relative clause to an external functional position (27b):

- b.

- [DP AgrD+the [AgrP boy [tAgr [CP [DP who tNP]]i [IP I met ti]]]]]

In other words, relative que behaves like a transitive D in these contexts. In contrast to demonstrative and interrogative Ds, relative que does not co-occur with its nominal complement inside the relative clause because the noun has risen further up.

- (28)

- a.

- Li

- I.read.PST

- [este

- this

- livro].

- book

- ‘I read this book.’

- b.

- [Que

- which

- livro]i

- book

- leste

- you.read.PST

- [que [livro]]i?

- which book

- ‘Which book did you read?’

- c.

- Não

- not

- gostei

- I.liked

- do

- of.the

- livroj

- book

- [que

- REL

- [livroj]]i

- book

- me

- me

- deste

- you.gave

- [que [livro]]i.

- REL book

- ‘I didn’t like the book that you gave me.’

Both raising derivations (27a) and (27b) are unexpected given general assumptions about the DP in Romance languages. In Bianchi’s (1999; 2000) as well as Kato & Nunes’ (2009) versions of raising, the nominal that is modified by the relative clause has a different internal structure than other DPs. In (27a), the external determiner subcategorizes for a CP; in (27b), the outer D-head takes as a complement an AgrP which does not include a NP. However, articles usually subcategorize for a NP (including its functional shells). In addition, Portuguese D-elements such as articles and clitic object pronouns cannot embed a CP complement or a relative clause (with the exception of free relative clauses, which have a completely different structure).

Nonetheless, the raising analysis has become widely accepted, primarily because it is able to account for reconstruction facts, i.e., contexts in which the head noun has to be interpreted in its argument position inside the relative clause. One famous example of a reconstruction effect is the binding of anaphors such as each other:

| (29) | Schachter (1973: 33) |

| The [interest in [each other]i]k [CP that [John and Mary]i showed tk] was fleeting. |

According to Principle A of the Binding Theory, anaphors like reflexives and reciprocals must be locally bound by their antecedent (Chomsky 1981) – which is not the case in (29) since each other is not c-commanded by its antecedent John and Mary. A raising account solves this issue by assuming that the anaphor is bound in its base position inside the relative clause before moving to its final position. However, it has been argued that Principle A does not necessarily have to be fulfilled before movement: according to Belletti & Rizzi (1988) and Lebeaux (2009), Principle A is a kind of “anywhere principle”, i.e., anaphors have to be bound in some moment during the derivation, at LF at the latest. If this is the case, structures like (29) do not necessarily speak in favour of a raising analysis.

On the other hand, relative clauses also display non-reconstruction effects, that is, contexts in which the head noun must not reconstruct inside the subordinate clause in order to render the derivation grammatical. For example, Principle C effects are often judged to be absent in relativization (cf. Bhatt 2002; Salzmann 2006; among others):

| (30) | Salzmann (2006: 28) |

| the [picture of Billi] that hei likes — |

A raising analysis would predict the ungrammaticality of (30) because the R-expression Bill would be bound by the co-indexed pronoun he under reconstruction – as Principle C has to be fulfilled at all levels of the derivation (cf. Belletti & Rizzi 1988; Lebeaux 2009). However, this is not the case, which speaks against the assumption that the head noun stems from inside the relative clause.

The discussion shows that the raising analysis cannot account for the whole range of reconstruction effects. Furthermore, raising is problematic regarding the interpretation of a restrictive relative clause as the intersection of two sets: a noun phrase marked by a restrictive relative clause cannot be interpreted as an intersection of the description of the noun and the relative clause if the head noun itself is part of the relative clause. Additional problems for the raising analysis are coordinated antecedents and case/theta role assignment, which we will address briefly here (cf. Alexadiou et al. 2000; among others).14

- (31)

- a.

- [O

- the

- homem

- man

- e

- and

- a

- the

- mulher]i

- woman

- [que__i]

- REL

- foram

- they.were

- detidos.

- arrested

- ‘The man and the woman who were arrested.’

- b.

- O

- the

- João

- João

- viu

- saw

- um

- a

- homemi

- man

- e

- and

- a

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- viu

- saw

- uma

- a

- mulherj

- woman

- [que__ i+j]

- REL

- foram

- they.were

- procurados

- wanted

- pela

- by.the

- polícia.

- police

- ‘João saw a man and Maria saw a woman who were wanted by the police.’

- c.

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- deu

- gave

- um

- a

- beijo

- kiss

- [IO-DAT

- ao

- to.the

- homem]

- man

- [SU-NOM

- que]

- REL

- te

- to.you

- falou

- talked

- na

- at.the

- festa.

- party

- ‘Maria gave the man a kiss that talked to you at the party.’

In (31a–b), the relative clause refers to a coordinated head noun, i.e. the plural conjunction of two singular DPs. (31a) is an instantiation of a Link (1984) “hydra” antecedent, which poses the question how a coordinated head, which is raised from inside the relative clause, can attach to two singular external determiners. (31b) shows a case of a split antecedent (Perlmutter & Ross 1970), where a plural relative clause modifies two singular head nouns, both of which occur in their own clause. According to Alexiadou et al. (2000: 14), “[i]t seems rather far-fetched to suppose that the antecedents [in (31b)] could have originated inside the relative clause (say, as a conjoined DP) to then be split and distributed across two clausal conjuncts after raising”.

In (31c), the head noun and the relativized position represent different kinds of syntactic positions, and therefore bear different cases and theta roles. If the head noun were to start off as a complement of the relativizer, it should already be marked for nominative. However, once it ends up in its superficial position, it should enter in agreement with the external determiner, which is part of a dative object. Therefore, the whole derivation should crash due to case mismatch, which it does not.

Brito (2005: 411ff.) makes another important observation for EP: there are good reasons to assume differences in syntax for restrictive and non-restrictive relatives, such as e.g., different relativizers. A raising approach à la Kayne (1994) or Bianchi (1999), however, claims raising for restrictives as well as non-restrictives, and therefore makes predictions about non-restrictive relative clauses that are hard to maintain. Essentially, some empirical facts of non-restrictive relative clauses in EP cannot be explained under a raising account, namely juxtaposed paratactics (32a), pseudo-appositive relatives (32b), non-restrictive relatives starting with a noun (32c), and sentential non-restrictive relatives (32d):

- (32)

- Brito (2005: 413f.)

- a.

- O

- the

- Conselho

- cabinet

- apresentou

- presented

- saudações.

- greetings

- Que

- REL

- ninguém

- nobody

- já

- no.longer

- esperava.

- expected

- ‘The Cabinet brought greetings. Which nobody had expected anymore.’

- b.

- Os

- the

- Portugueses,

- Portuguese

- aqueles

- those

- que

- REL

- têm

- they.have

- dinheiro,

- money

- viajam

- they.travel

- muito.

- much

- ‘The Portuguese, those that have money, travel a lot.’

- c.

- Eles

- they

- não

- not

- se

- REFL

- dão

- they.give

- bem

- well

- há

- since

- algum

- some

- tempo,

- time

- problema

- problem

- que

- REL

- se

- REFL

- agravou

- aggravated

- desde

- since

- o

- the

- verão.

- summer

- ‘They haven’t gotten along well since some time, a problem that has become worse since summer.’

- d.

- O

- the

- famoso

- famous

- político

- politician

- demitiu-se,

- resigned-REFL

- o

- the

- que

- REL

- chocou

- shocked

- o

- the

- país.

- country

- ‘The famous politician resigned, which shocked the whole country.’

All of these four empirical phenomena pose serious problems for a raising account because it seems not at all clear what element exactly should be raised, and how the structure could be derived in this way.

Finally, Brito (2005: 412) points out a structural problem: in order to derive that appositive relative clauses are outside the scope of the external D, a raising analysis has to assume that after movement of the relativized DP to the left periphery of the relative clause and the extraction of the head noun, the remaining relative clause TP has to move covertly to a position above the D-head (Bianchi 1999; Kayne 1994). The motivation for this movement is problematic, however, because movement at LF is supposed to enable constituents to scope over others, and not to escape their scope (cf. Brito 2005: 412).

Concerning the analysis of EP restrictive relative clauses with que, a raising analysis would only be appropriate for restrictive subject and object relative clauses: one could argue, like Kato & Nunes (2009), that the reason why only que is allowed as a relativizer in these contexts, and no other element, is that que is left behind by its nominal complement, which raises further up. However, in all the other contexts in which we have argued for que to be an e-type kind of pronoun like the il quale-kind in Cinque (2008), this derivation is not an option. Therefore, we would be forced to assume two different derivations for relative clauses in EP: a raising derivation for restrictive subject and object relatives, and a different one for restrictive oblique and all appositive relatives. The idea that a language possesses two different relative clause derivations is not new, however, until now, this has been motivated for reasons of interpretation (cf. Bhatt 2002; Carlson 1977; Cinque 2015), and not depending on the relativized syntactic position. We consider this complication as well as the different problems of the raising analysis discussed so far to be serious enough to reject raising as the correct derivation for restrictive relatives in EP.

A second kind of analysis, which was proposed in order to account for the before mentioned reconstruction and non-reconstruction effects in relative clauses, is the matching analysis (Chomsky 1965; Lees 1960; 1961; Salzmann 2006; Sauerland 1998; 2003; among others). According to this perspective, there are two instances of the head noun: one in external position, selected by the external determiner, the other one relative clause-internal, selected by the relative determiner (cf. example 33). The internal instance is then deleted on PF under identity with the external head.15 Crucially, the external and the internal head are not related via a movement chain, which is marked by inferior numbers in Salzmann’s system, but rather by ellipsis, marked by indices:

| (33) | Salzmann (2006: 10) |

| the [book]i [CP [Op/which booki]1 John likes__1] |

In order to account for non-reconstruction effects like in (30), Sauerland (1998; 2003) proposes that instead of a fully identical NP, a pronominal element could play the role of the internal head noun (vehicle change), in a parallel fashion to ellipsis constructions. In this way, the co-reference between the R-expression and the pronominal subject inside the relative clause can be captured: what is reconstructed inside the relative clause is not the whole R-expression, but a pronominal substitute, which obeys Principle B. Therefore, no Principle C effects arise.

| (34) | Sauerland (2003: 221f.) | |

| a. | Pictures of Johni which hei displays prominently are likely to be attractive ones. | |

| b. | [picture of Johni]j λx which hei displays [x, onej] | |

The matching analysis also poses a number of difficulties, e.g., with respect to the licensing of idioms (cf. Vergnaud 1974):

| (35) | Webelhuth, Bargmann & Götze (in print: 5; taken from McCawley 1981)16 |

| Parky pulled the stringsi [RC that ti/stringsi got me the job] |

A matching analysis would assume two instances of the idiom chunk strings: an external one outside the relative clause, correctly bound by the other idiom chunk pulled, and an internal one – which would not be bound at all. In principle, this derivation should crash. Since it does not, additional assumptions have to be made, e.g., a default reconstruction interpretation and exceptional deletion on LF (cf. Salzmann 2006: 126ff).

Furthermore, the vehicle change-operation, represented above as an explanation for non-reconstruction under a matching perspective (cf. example 30) seems to be problematic for EP. When EP relative que is a D-element, it is unclear how it could possibly select for a pronominal (DP) complement, given the fact that pronouns are DPs and D-heads embed nominal projections and not other DPs.17 If one would assume that only the pronominal represents the internal head, que would have to be interpreted as a complementizer – a perspective that we have argued against. Finally, if one assumes a pronoun to be the mediating element between the external head and the relative clause-internal trace, the idea of a matching derivation in a stricter sense is lost. If an element in SpecCPrel values its phi-features according to the external head, the respective element can also be a demonstrative-like DP [DP que].

The discussion of existing analyses leads us to believe that the head internal proposals, i.e. the raising and the matching analyses, lead to serious theoretical and empirical problems regarding both restrictive and appositive relative clauses. Therefore, we will explore a modification or head external analysis (cf., among others, Boef 2012; Brito 2005; Chomsky 1977; Heim & Kratzer 1998; Montague 1974; Partee 1975; Webelhuth, Bargmann & Götze in print) for all relative clauses in EP. In opposition to raising, the head noun does not originate inside the relative clause, but as a complement of the external determiner. Inside the subordinated clause, only a relative operator is moved to the C-domain, where it becomes co-indexed with the external head noun.

Assuming that que is a transitive demonstrative, we propose that it entails an empty nominal element, which is referentially identified by the head noun:

- (36)

- O

- the

- livroi

- book

- [CP [DP

- que

- REL

- [NP

- ei]]

- C

- [TPli

- que e …

- I.read.PST

- ‘The book that I read.’

The modification analysis resolves the problem of case assignment of the raising analysis because, syntactically, two different noun phrases are involved, which can bear different case markings, different thematic roles, and distinct syntactic functions. Semantically, only one noun phrase (the description of the head noun) is present, which identifies the reference of the empty noun phrase inside the relative clause. This guarantees that the description of the head noun and the description of the relative clause are in principle independent enough to ensure an intersective interpretation, but connected in the sense that the head noun referentially binds the empty noun phrase embedded by the relative determiner que. Also, instances of idiom licensing as in (35) can easily be accounted for: since there is no relative clause-internal head noun, the problem of the impossibility of licensing a floating idiom chunk does not even come up.

As for the reconstruction effects, Brito (2005: 409) shows that they are also an issue in the relative clauses of EP, e.g., the binding of anaphors:

- (37)

- O

- the

- retrato

- picture

- de

- of

- si

- REFL

- próprio

- self

- que

- REL

- o

- the

- João

- João

- tirou

- took

- ficou

- stayed

- muito

- very

- bem.

- good

- ‘The picture of himself that João took was very good.’

However, we believe that reconstruction effects are not problematic in this analysis because the empty noun phrase in the relativizer [DP que [NP e]] is referentially connected to the head noun outside the relative clause and to its own copy in argument position.18 Instead of assuming syntactic reconstruction, as the raising analysis does, some kind of semantic reconstruction could be employed, as has already been proposed for scope interpretation (cf. Boef 2012; Sternefeld 2001). As argued before, the different levels at which Binding Principles apply can be taken as further arguments in favour of a modification analysis.

Assuming a modification analysis for subject and object relative clauses, we expect the relative clause itself to be attached in the spine of the DP in a similar way as other (restrictive) modifiers. We assume that this position is SpecnP or some other functional projection hosting restrictive elements between NumP and NP19 (cf. also Alexandre 200020):

As becomes clear in (38), restrictive relative clauses are base generated pre-nominally. The superficial order Det-N-RC is achieved via obligatory head movement of the nominal to one of its functional projections, which has been argued for independently (cf. Cinque 1995).21

4. Summary and conclusions

We have argued against an analysis of relative que as a complementizer and have proposed that in European Portuguese, relative que is a demonstrative that comes in two guises. In appositive as well as restrictive indirect object or prepositional relative clauses, where que is interchangeable with o qual, que can be analysed as an intransitive demonstrative, similar to an e-type pronoun. In restrictive subject and object relative clauses, on the other hand, que is a transitive demonstrative and selects for a silent nominal complement.

With respect to the derivation of relative clauses, three competing analyses are available: a raising, a matching, and a modification analysis. Since there are several theoretical and empirical problems for the raising and the matching analyses, we have argued in favour of a modification analysis. We believe that this is an adequate analysis in order to account for the derivational particularities in EP.

On the basis of an observed incompatibility of demonstratives with restrictive relative clauses, we have argued that demonstratives and relative que share common features. We have concluded that restrictive relatives and demonstratives are base-generated in the same position: a specifier of a nominal projection between DP and NP. The superficial, post-nominal order of the relative clause is then achieved via obligatory movement of the noun to at least NumP (cf. Alexandre 2000). This proposal is in concordance with general assumptions about the structure of DP in European Portuguese.

Notes

- This work has been carried out as part of the research project “The relative clause cycle. Accounting for the variation in Italian and Portuguese relative clauses” funded by the German Science Foundation (DFG) in the framework of the research group 1783 on “Relative Clauses”, Goethe University Frankfurt. [^]

- Interestingly, in some cases, this replacement seems to be mandatory, e.g. in the case of (i), an appositive relative clause modifying a proper noun, in which the relativizer is selected by the preposition com, ‘with’:

[^]

- (i)

- A

- the

- Ana,

- Ana,

- com

- with

- quem/

- REL/

- ??com

- with

- que

- REL

- discuto

- I.discuss

- muito’

- a.lot,

- não

- not

- me

- me

- escreve.

- writes

- ‘Ana, with whom I argue a lot, doesn’t write me.’

- This is expected if agreement, as we understand it, is an abstract syntactic operation that may or may not be morphologically visible. [^]

- According to the authors, complementizers and pronouns are quantifier-like elements that are linked to different types of classifiers. We will not go into the details of this analysis. [^]

- Unfortunately, the authors do not provide a formula for the relative clause. [^]

- This incompatibility of that with a [+human] subject is also found in subject cleft sentences (ia) and subject relative clauses with indefinite head nouns (ib):

In object cleft sentences (iia) and in object relative clauses with indefinite head nouns (iib), however, that is compatible with a [+human] interpretation.

(i) a. In fact it was Mary who/*?that got me interested in linguistics. b. I met somebody who/*that told me you were back. [^](ii) a. In fact it was Mary who/?that I learned linguistics from in the first place. b. I met somebody that you’ve known for a long time. - This DP involves que as a determiner plus the head noun ([DP que + head noun] (Kato & Nunes 2009; Kayne 2010). The nominal later rises to a position outside the relative clause (raising analysis). [^]

- A reviewer rightfully points out that there is no full agreement on the diachrony of complementizer que: Herman (1963) claims that the introducing element of declarative sentential complements is actually a development of a relative element. This claim would support a view that there is no complementizer que, but only instances of relativizer-like elements. This is in line with Kayne (2010), who claims that there is no complementizer this due to the absence of a relativizer this. He claims that sentential complements are actually relative clause structures, and they can only be introduced by that, a relative demonstrative. In this sense, we do not think that the non-agreement with respect to the diachrony of relative and complementizer que is a problem for our claim here. [^]

- We leave aside wh-in-situ questions, which serve as so-called Echo Questions in European Portuguese. [^]

- Carvalho (2011: 59) also assumes that in the case of postnominal demonstratives, the noun has to move higher up in order to guarantee reference of the constituent. [^]

- In this sense, we adopt an analysis similar to that of Brito (1991) for these contexts. [^]

- Some native speakers accepted this example although they found it somehow marginal; others find it completely ungrammatical. [^]

- Note, however, that Cardoso (2010) argues that non-restrictive relative clauses introduced by o qual are integrated in EP. [^]

- For an extensive list regarding empirical problems for a raising analysis in general, but also especially for English and German, see Borsley (1997; 2001); Heck (2005); Webelhuth, Bargmann & Götze (in print). [^]

- We adopt Salzmann’s (2006) marking of the internal head by outlines. [^]

- This kind of idiom licensing is also problematic for a raising analysis. [^]

- In fact, this argument only holds for DP-like strong pronouns and not for pronouns with a reduced structure (cf. Cardinaletti & Starke 1999; Déchaine & Wiltschko 2002). [^]

- In addition, this has the desirable result that [que[e]] has been independently proposed for EP interrogative clauses by Ambar (1992). However, the difference between relative clauses and interrogative clauses with [que[e]] is that relative clauses do not necessarily trigger subject-verb inversion, whereas interrogative clauses with [que[e]] do.

- (i)

- Ambar (1992: 187)

- a.

- *Que

- what

- o

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- ofereceu

- gave

- à

- to.the

- Joana?

- Joana

[^]- b.

- Que

- what

- ofereceu

- gave

- o

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- à

- to.the

- Joana?

- Joana

- It is generally agreed that demonstratives are base generated in a low position and then move to SpecDP in order to make the specifier of a strong DP visible (Brugè 2000; 2002; Giusti 1997; 2002; Grohmann & Panagiotidis 2005; Panagiotidis 2000; Shlonsky 2004). One piece of evidence for the postnominal base position is that in some languages, demonstratives may occur post-nominally (Sp. El libro este ‘the book this’). Although this is not the case in EP, the post-nominal occurrence in (15a–b) may be interpreted in terms of the demonstrative occurring in its postnominal base position. [^]

- Alexandre (2000: 137) calls her proposal [NP CP NP]: she argues that the relative clause is base generated in an additional specifier position of the head noun NP. The NP containing the head noun rises to SpecNbP and finally to SpecGenP, attracted by the external determiner. In this way, the superficial word order D NP RC is achieved. [^]

- Note, however, that Cinque’s (1995) N-movement has only been proposed for Romance. As for other linguistic systems, like Germanic languages, which do not possess the Romance-like N-movement, the order D-N-RC has to be accounted for in a different way. For a comparison of EP and English DPs modified by restrictive relative clauses, cf. Alexandre (2000). [^]

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

N. M. P. Alexandre, (2000). A estratégia resumptiva em relativas restritivas do Português Europeu [The resumptive strategy in restrictives relative clauses in European Portuguese] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Portugal: Universidade de Lisboa.

A. Alexiadou, L. Haegeman, M. Stavrou, (2008). Noun phrase in the generative perspective. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110207491

A. Alexiadou, P. Law, A. Meinunger, C. Wilder, (2000). Introduction In: A. Alexiadou, P. Law, A. Meinunger, C. Wilder, The syntax of relative clauses. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 1. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1075/la.32.01ale

M. Ambar, (1992). Para uma sintaxe da inversão sujeito-verbo em português [Towards a syntax of subject-verb inversion in Portuguese]. Lisbon: Colibri.

P. Barbosa, (n.d.). Perfil Sociolinguístico da Fala Bracarense [Sociolinguistic profile of the Bracarense dialect]. Braga, Portugal: Universidade do Minho. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/projectofalabracarense/.

A. Belletti, L. Rizzi, (1988). Psych-verbs and θ-theory. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 6 (3) : 291. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf00133902

R. Bhatt, (2002). The raising analysis of relative clauses: evidence from adjectival modification. Natural Language Semantics 10 : 43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1015536226396

V. Bianchi, (1999). Consequences of antisymmetry: Headed relative clauses. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110803372

V. Bianchi, (2000). The raising analysis of relative clauses: A reply to Borsley. Linguistic Inquiry 31 (1) : 123. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/002438900554316

K. Birkner, (2008). Relativ (satz)konstruktionen im gesprochenen Deutsch [Relative (clause) constructions in spoken German]. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110210750

E. Boef, (2012). E. Boone, K. Linke, M. Schulpen, Doubling in Dutch restrictive relative clauses: Rethinking the head external analysis. Proceedings of ConSOLE XIX. Leiden Universiteit Leiden : 125.

R. Borsley, (1997). Relative clauses and the theory of phrase structure. Linguistic Inquiry 28 (4) : 629. DOI: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178997.

R. Borsley, (2001). More on the raising analysis of relative clauses. UK: University of Essex. Unpublished manuscript.