1. Introduction

Traditionally known as one of the nominal forms of the verb1 (aside from gerunds and participles), Portuguese infinitives are orthographically represented by an -r adjacent to a verbal stem, as in canta-r2 (‘sing’) and in spite of constituting a morphophonological group, since they are all expressed with /R/,3 they are not morphosyntactic homogeneous. In any case, it is noteworthy that the infinitive-marking – i.e., the omnipresence of /R/ – is a strong piece of evidence to rule out an analysis where Portuguese has “bare VPs” or an infinitive-structure going up just until VoiceP – contra Cyrino & Sheehan (2018).

On infinitives, a lot of work has been devoted to the distinction between nominal and verbal infinitives, such as Basílio (1987), Khedi (1992) and Resende (2016, 2020) for Brazilian Portuguese (BP); Raposo (1987a, b), Brito (2012, 2013), Oliveira (2014) for European Portuguese (EP), to mention a few. In turn, syntactically the concerns revolve around the tense of infinitives and their relation to other phrases and manly to what kind of syntactic setting (raising, control, etc.) relates them – see Stowell (1982), Bošcović (1996), Martin (2001), Landau (2004), Wurmbrand (2014), and also Raposo (1987a), Ambar (2000), Pires (2006), Gonçalves, Cunha & Silvano (2016), Gonçalves, Santos & Duarte (2014) for discussion on EP and Modesto (2007) and Resende (2021) on BP.

In addition to tense, some authors have also argued for grammatical aspect in some infinitives forms in Italian (Zucchi, 1993), Spanish (Demonte & Varela, 1997), French (Sleeman, 2010), German (Alexiadou, Iordăchioaia & Schäfer, 2011), BP (Lunguinho, 2006; Rodrigues, 2006; Resende, 2016, 2020) and EP (Brito, 2012, 2013). Furthermore, semantically, scholars have provided a formal analysis for verbal infinitives, as Chierchia (1985), Abusch (2004); Silvano & Cunha (2016) on EP and Ferreira (2020) on BP.

The aim of this paper is to contribute to the debate on the characterization of the morphosyntax and semantics of Portuguese infinitives, by proposing a morphosemantic derivation that generates the most common structures associated with the /R/-morpheme: a nominal, a verbal and a “mixed” one – as we call it. Moreover, we address the issue of tense and aspect in these forms and argue that all three types of infinitives share the same derivation up to AspP, which – we claim – is underspecified in infinitives and competes with the participle (-d-), perfective, and the gerund (-nd-), imperfective – the other non-finite forms.

Thus, because of scope, we focus our analysis on the morphemes (the pieces), which are the building blocks of infinitive forms and on the semantic readings they convey and leave aside some syntactic issues for further investigation. Specifically, we provide a formal analysis for the subatomic semantics derived from the infinitive(s) structure. For that, this paper is organized as follows: in § 2 we present a survey of Portuguese infinitives, providing an empirical description showing their morphosyntactic properties. In § 3 we offer a formal morphosyntactic treatment for the phenomena, using Distributed Morphology’s tools (Halle & Marantz, 1993, and subsequent work). Finally, in § 4 we propose a semantic analysis for the structures given in § 3. In short, we show that all instances of infinitive can be accounted for by the same formal pieces in a high compositional fashion tying together morphosyntax and semantics.

2. A survey on the morphosyntax of Portuguese infinitives

In this section, following insights from the Portuguese literature, we argue that infinitives morphosyntactically split off in three groups, namely, (i) nominal infinitives, (ii) verbal infinitives and (iii) “mixed” infinitives – in the sense of Chomsky (1970). Nominal infinitives are morphologically nouns, in that they exhibit properties typically associated to the nominal class, such as precedence by determiners in (1), nominal plural marking in (2), modification by adjectives in (3). These infinitives are usually treated as a nominalization from a verbal stem, since they license argument structure and – given their nominal character – have their arguments introduced by prepositions, as in (1b) and (3).

- (1)

- (a)

- A

- to

- meu

- my-masc

- ver…

- see-inf

- ‘in my point-of-view’

- (b)

- O

- the-masc

- cantar

- sing-inf

- dos

- of-the

- pássaros.

- birds

- ‘the birds’ singing’

- (2)

- (a)

- Os

- the-masc-pl

- deveres

- must-inf-pl

- de

- of

- todo

- every

- cidadão.

- citizen

- ‘every citizen’s duty’

- (b)

- O

- the-masc

- Brasil

- Brazil

- tem

- has

- três

- three

- poderes:

- can/may-inf-pl:

- executivo,

- executive,

- legislativo,

- legislative,

- judiciário.

- judiciary

- ‘Brazil has three government branches: executive, legislative, judicial’

- (3)

- (a)

- O

- the-masc

- mover

- move-inf

- brusco

- sudden

- (/*bruscamente)

- (*suddenly)

- da

- of-the

- caixa.

- box

- ‘the sudden (/*suddenly) moving of the box’

- (b)

- Um belo

- a-masc

- (/*belamente)

- beautiful(*ly)

- nascer

- born-inf

- do

- of-the

- sol.

- sun

- ‘a beautiful sunset’

Basílio (1987) and Brito (2013) claim that dever (‘must’) and poder (‘can/may’) in (2) – and a few others – are instances of “lexicalized infinitives” and therefore should be seen as “special” and should not be analyzed as prototypical nominal infinitives – as (1b) or (3a). However, although we recognize that they convey additional semantic content,4 our working hypothesis is that they can be treated as belonging to the same nominal group, because dever and poder exhibit the same “pieces” (root, verbal theme vowel, infinitive-marking), convey an event/state-related reading and license argument structure, as shown in (4).

- (4)

- (a)

- O

- the

- dever

- must-inf

- de

- of

- servir

- serve-inf

- o

- the

- país

- country

- (de todo soldado).

- (of every soldier)

- ‘every soldier’s duty of serving the country’

- = the state of obligation of serving the country

- (b)

- O

- the

- poder

- can-inf

- de

- of

- fazer

- make-inf

- com que os

- that

- casais

- couples

- façam as

- make

- pazes

- peace

- (daquele terapeuta).

- (of that therapist)

- ‘that therapist’s power of making couples make up’

- = the state of being able to make the couples make up

On their turn, verbal infinitives appear in a wider range of syntactic contexts, from subject- and complement-clauses to imperatives. Morphologically, verbal infinitives are verbs, since they display prototypical verbal properties, such as verbal (person/number-) inflection in (5), in contexts where the uninflected infinitive would give rise to the ECM-structure; occurrence as a complement of an auxiliary verb in (6); modification by adverbs in (7). Moreover, differently from nominal infinitives, the complement of verbal infinitives need not to be introduced by a preposition. Syntactically speaking, verbal infinitives can appear in ECM-contexts in (5), in raising-contexts in (6) and in control-contexts in (7). Again, for our purposes, it is not crucial to discuss the syntactic structures underlying these examples.

- (5)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Mary

- fez

- made

- os

- the

- meninos

- boys

- comerem

- eat-inf-agr

- a

- the

- sopa.

- soup

- ‘Mary made the boys eat the soup’

- (6)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Mary

- vai

- goes-Aux

- comprar

- buy-inf

- a

- the

- casa

- house

- este

- this

- ano.

- year

- ‘Mary is going to buy the house this year’

- (7)

- O

- the

- ministro

- minister

- conseguiu

- managed

- mover

- move-inf

- rapidamente

- quickly-adv

- (*rápido)

- (*quick-adj)

- a

- the

- caixa.

- box

- ‘the minister managed to quickly move the box’

Regarding the verbal inflection in (5), the so-called “inflected infinitive”, it is a research topic in its own – see Raposo (1987a), Pires (2006), Modesto (2007), Gonçalves, Santos & Duarte (2014) to mention a few. For our purposes, it suffices to show that this verbal agreement (Agr) is a property associated to the T head and hence licensed only in (morphological) verbal environments. Of course, the presence of TP is not sufficient to license infinitive-inflection; rather, it emerges only in few syntactic contexts, such as subject-sentences, adjunct-sentences, ECM-environments and some control-contexts – see Raposo (1987a) and Modesto (2007).

In the example in (6), the infinitive appears as a complement of an auxiliary verb. Following Gonçalves & Costa (2002), this subcategorization holds, because they are verbal elements. Thus, complements of auxiliary verbs are verbal infinitives. As for (7), there is a non-inflected infinitive occurring in a control-environment – a topic we do not discuss in this paper. Hence, we employ “control” and “raising” only as descriptive labels, since what is at stake for our analysis are the infinitive (morphological) pieces that allow for them to occur in certain syntactic environments.

Although the literature agrees on the distinction between nominal and verbal infinities, there is no consensus on mixed infinitives – but see Brito (2012, 2013) for EP and Resende (2016, 2020) for BP. These infinitives are mixed in that display both verbal and nominal properties. However, we do not claim thereby there is a third morphological type of infinitive; rather, we claim that in addition to the infinitives that are verbal and appear in verbal contexts and to the infinitives that are nominal and appear in nominal contexts, there is another syntactic setting, which is mixed, that is, an infinitive which is verbal and appears in a nominal context.

Therefore, they are mixed in that they exhibit properties of both other types. Specifically, with nominals, they share the property of being preceded by determiners, see (8) and also Brito (2013). With verbs, they share the property of allowing for infinitive-inflection in (8), assigning accusative Case to their complement in (9), licensing adverbial modifiers in (10).

- (8)

- (a)

- O

- the-masc

- saber

- know-inf

- matemática

- mathematics

- ajuda

- helps

- no

- in-the

- desenvolvimento

- development

- do

- of-the

- cérebro.

- brain

- ‘knowing math helps the development of the brain’

- (b)

- O

- the-masc

- zombarem

- mock-inf-agr

- de

- of

- certos

- certain

- abusos

- abuses

- desse

- of this

- nosso

- our

- apego

- attach

- aos

- to

- diminutivos.5

- diminutives

- ‘their mocking of our excessive attachment to little things’

- (9)

- Ao

- to-the-masc

- comprar

- buy-inf

- uma

- a

- casa

- house

- (/comprá-la),

- (she-acc),

- você

- you

- deve

- must

- assinar

- sign

- o

- the

- contrato.

- contract

- ‘by buying a house, you must sign the contract’

- (10)

- Ao

- to-the

- movermos

- move-inf-agr

- bruscamente

- suddenly-adv

- (/*brusco)

- (/*sudden-adj)

- a

- the

- caixa…

- box…

- ‘by our suddenly moving the box’

In the examples from (8) to (10), despite of “internal” properties being verbal (that is, they are verbal infinitives), the presence of the determiner (in the case, the D head) is evident: o (the-masc-sg) in (8), (9) and (10). In § 2, we account for this “mixed” behavior. In any case, the fact that (morphologically) verbal infinitives can occur inside DPs, with overt Ds, supports the idea that there can be other “nominal infinitive-clauses” (hence, mixed) even when the D is not overt. This is the case of the subject-infinitive clauses and some embedded infinitive-clauses, as in (11)–(14).

This reasoning traces back to Raposo’s (1987b) idea of “Imax = NP”, in that inflected infinitive’s Agr must be Case-marked and to Raposo’s (1987a) insight that infinitive clauses are nominal projections. These conclusions are stemmed on the observation that as any other nominal, (some) infinitive-clauses must be Case-marked, as in (11). Additionally, such infinitives can also appear in typical nominal positions as subjects, in (12). Moreover, Resende (2021) takes clefting as a piece of evidence for claiming that BP can cleft DPs, but not CPs. And, Iordăchioaia (2013) argues that pronominalization attests the presence of DP (even with default φ-features), in (14).

- (11)

- (a)

- A

- the-fem

- Ana

- Anne

- deseja / sonha / espera

- desires / dreams / hopes

- morar

- live-inf

- em Paris.

- in Paris

- ‘Anne wants / hopes / expects to live in Paris’

- (b)

- O

- the-masc

- desejo / sonho / esperança *(de)

- desire / dream / hope (of)

- morar

- live-inf

- em Paris.

- in Paris

- ‘the desire / dream / hope of living in Paris’

- (12)

- (a)

- Tocar

- play-inf

- piano

- piano

- frequentemente

- often-adv

- (/*frequente)

- (*often-adj)

- estimula

- stimulates

- o

- the

- cérebro.

- brain

- ‘often playing the piano stimulates the brain’

- (b)

- João

- John

- e

- and

- Maria

- Mary

- tocarem

- play-inf-AGR

- piano

- piano

- frequentemente

- often-adv

- incomoda

- annoys

- os

- the

- vizinhos.

- neighbors

- ‘John and Mary’s often playing the piano annoys the neighbors’

- (13)

- (a)

- É

- is

- [morar]?P

- [live-inf]

- em

- in

- Paris

- Paris

- que a

- that

- Maria

- Mary

- quer.

- wants

- ‘living in Paris is what Mary wants’

- (b)

- É

- is

- [uma moradia]DP

- [a place to live]

- em

- in

- Paris

- Paris

- que a

- that

- Maria

- Mary

- quer.

- wants

- ‘a house in Paris is what Mary wants’

- (c)

- *É

- is

- [que o João more em Paris]CP

- [that the John lives-subj in Paris]

- que a

- that

- Maria

- Mary

- quer.

- wants’

- (14)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Mary

- quer

- wants

- [comer pizza]DP,

- [eat-inf pizza],

- e o

- and the

- João

- John

- também

- also

- [o]DP

- [he-acc-sg]

- quer.

- wants

- ‘Mary wants to eat pizza and John wants it too’

In short, in the spirit of Brito (2012, 2013), Oliveira (2014) and Resende (2020), we assume that the data in (8)–(10) are instances of mixed nominalizations, in the sense of Chomsky (1970), due to the presence of the determiners. Below we give arguments that support this assumption. Additionally, the conclusion that some infinitive-phrases can be nominal could also apply to (11)–(14), given their nominal behavior. However, because of (syntactic) scope, we take to represent the mixed group only infinitives that occur as subjects or those which are introduced by determiners or prepositions and leave aside the issues that raise because of the grammatically of (11), (13) and (14).

Morphologically, verbal infinitives fall into the (verbal) template shown in (15), in the spirit of Camara Jr. (1970). In § 3 we show that infinitives are built respecting these slots.

| (15) | Verbal template in Portuguese (traditional version): |

| Root + Verbal Theme Vowel + Tense/Mood/Aspect + Number/Person |

Whether or not verbal infinitives appear in verbal contexts, the issue underlying their morphosyntax does not lie on their morphological composition (i.e. the projections /morphemes they have), but in the feature-specification of these projections that allow for them (or not) to appear in different syntactic environments, particularly as regards the features of T (the slot for Tense/Aspect in (15)). Following Stowell (1982), Landau (2004) and others, there are two kinds of reading for non-finite TP-phrases in relation to the matrix clause they co-occur with: futurate to the matrix verb (what literature has also called “irrealis”) or simultaneity to the matrix verb (the “anaphoric” reading, to employ Landau’s (2004) terminology). Examples from these two types are shown in (16), (17) and (18), where amanhã (‘tomorrow’) highlights the futurate reading.

- (16)

- (a)

- O

- the

- empresário

- business man

- planejou

- planned

- viajar

- travel-inf

- (amanhã).

- (tomorrow)

- ‘the business man planned to travel (tomorrow)’

- (b)

- O

- the

- empresário

- business

- conseguiu

- man

- viajar

- got

- (*amanhã).6

- travel-inf (tomorrow)

- ‘the business man managed to travel (*tomorrow)’

- (17)

- (a)

- A

- the

- Carol

- Carol

- mandou

- ordered

- o

- the

- André

- André

- (/o mandou)

- (/him ordered)

- limpar

- clean-inf

- o

- the

- armário

- locker

- (amanhã).

- (tomorrow)

- ‘Carol ordered Andrew (/him) to clean the locker (tomorrow)’

- (b)

- A

- the

- Carol

- Carol

- viu

- saw

- o

- the

- André

- Andrew

- (/o viu)

- (/ him saw)

- limpar

- clean-inf

- o

- the

- armário

- locker

- (*amanhã).

- (tomorrow)

- ‘Carol saw Andrew (/him) clean the locker room (*tomorrow)’

- (18)

- (a)

- A

- the

- névoa

- fog

- deve

- must

- cobrir

- cover-inf

- a

- the

- cidade

- city

- (amanhã).

- (tomorrow)

- ‘the fog must cover the city (tomorrow)’

- (b)

- A

- the

- névoa

- fog

- parece

- seems

- cobrir

- cover-inf

- a

- the

- cidade

- city

- (*amanhã).

- (tomorrow)

- ‘the fog seems to cover the city (*tomorrow)’

The examples (16), (17) and (18) show that in Portuguese the futurate/anaphoric distinction cannot be associated to a specific syntactic environment, since in (16) both sentences are obligatory control-constructions; in (17), we have two examples of ECM; in (18), both (a) and (b) are instances of raising. In these sentences, the compatibility with amanhã (‘tomorrow’) highlights the futurate reading, whereas their incompatibility signals that the reading is anaphoric and hence hinges on the morphological setting of the finite verb: past morphology in (16) and (17), present in (18). In this later case, the main point is that the infinitive form has a futurate reading although the modal verb has a present-tense morphology.

As for mixed infinitives, although they are embedded in DPs, they project T, which is supported by three additional tests, namely, (i) they assign nominative Case to the subject (Modesto, 2007), as in (19); (ii) they are modifiable by TP-adjuncts (Zucchi, 1993) differently from nominal infinitives, as in (20); (iii) they host a landing site for a moved clitic (Iordăchioaia, 2013), which is a property of T, but not N’s, as in (21).

- (19)

- Eu

- me-nom

- (*me/*mim)

- (me-acc/me-dat)

- chegar

- arrive-inf

- atrasado

- late

- é

- is

- difícil.

- rare

- ‘it is rare of me to arrive late’

- (20)

- (a)

- Ao

- to-the-masc

- [TP estar sempre]

- [be-inf always]

- alheio

- foreign

- às notícias,

- to-the news,

- você

- you can

- pode

- end up

- acabar alienado.

- alienated

- ‘by always being away from the news, you might end up alienated’

- (b)

- *O

- the-masc

- [NP nunca bater]

- [never ring-inf]

- dos

- of-the

- sinos

- bells

- preocupou

- concerned

- o

- the

- padre.

- priest

- ‘the never ringing of the bells worried the priest’

- (21)

- (a)

- [TP sentir-se]

- [feel-inf oneself]

- sozinho

- alone

- é

- is

- comum

- common

- hoje em dia.

- nowadays

- ‘feeling alone is something common these days’

- (b)

- [TP sei sentir <sei>] sozinho é comum hoje em dia.

- (c)

- [NP O sentir-se] sozinho é comum hoje em dia.

- (d)

- *[NP O sei sentir <sei>] sozinho é comum hoje em dia.

In (19), the fact that the only form of the pronoun is nominative endorses Modesto’s (2007) analysis that the infinitive in subject clauses is always inflected. In addition, Raposo (1987a) argues that inflected infinitives, like finite clauses, take lexical subjects, whereas non-inflected infinitives take PRO. In (20a) the infinitive is embedded in a DP, but the infinitive is not a noun, since it can license TP-adverbs, such as sempre (‘always’), nunca (‘never’), etc., what is not possible for nominal infinitives like (20b), whose nominal nature is attested by the preposition de (‘of’) introducing the complement. Regarding (21), proclisis is allowed only if the verbal form has a position for hosting it, which is taken as a property of T; thus, mixed infinitives allow for proclisis differently from nominal infinitives, as in (21d).

Hence, in this scenario, although mixed infinitives share external properties with nominals (they are headed by D), they share internal properties with verbal infinitives. Thus, we conclude, taking insights from the literature, that one may detect three types of infinitives, namely, a nominal, a verbal, and a mixed one. As we discuss in § 3, important consequences follow from this conclusion. Moreover, we show that mixed infinitives are not couched in the futurate/anaphoric distinction, what suggests that they are not only syntactically different, but also semantically (and feature-) distinct.

3. The pieces of the infinitives

In § 2 we showed that infinitives can be divided into three structures, according to their morphosyntactic properties: prototypically nominal and verbal infinitives, and a mixed group, which are structurally verbs, but appear in typically nominal positions, that is, inside DPs.

In the traditional description, according to which infinitive is one of the nominal forms of the verbs, the lexicon lists lexical entries; verbal infinitives are primes and other types of infinitives are derived from them or one of their (nominal) forms. Of course, nominalization is, strictly speaking, one of the nominal forms of the verb. However, if cantar (‘to sing’) is a nominal form of the verb, it is unclear why canto (‘song’), cantoria (‘singing’) or cantor (‘singer’) could not fall into the description one of the nominal forms of the verb – see Oliveira (2014) and Resende (2020) for discussion on Portuguese.

This idea tracing back to the Traditional Grammar view (and underlying lexeme-based approaches to morphology) struggles with both empirical adequacy and theoretical plausibility. In spite of being the quotation verbal form for Portuguese and is also one of the most frequent forms in the language (given the range of syntactic contexts where they can appear (Oliveira, 2014; Resende, 2020), there is no reason to presume that the lexicon lists inflected forms or even that there are some either morphological or lexical operation changing infinitive verbal forms into nominal forms – by means of zero-affixation, for instance.

Moreover, mixed infinitives show that the verbal/nominal labeling is not enough and also suggest that the different properties of these forms are indeed structurally and semantically determined, as we will show below. In this paper, by assuming Distributed Morphology’s framework, we argue that all infinitive forms – as any other “word” in the language – are syntactically derived. Thus, there is no “prime” form. Words are built out of roots and abstract syntactic-semantic features, devoid from phonological content, by the same syntactic operations used for building phrases and sentences, namely, Merge, Move and Agree (Halle & Marantz, 1993, 1994; Embick & Noyer, 2007). Being so, any infinitive is built out of a root and a verbalizer head vo, which turns the root into a verbal structure – ultimately in this case, into a verbal stem.

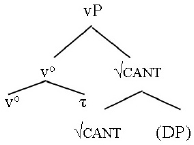

We showed in § 2 that infinitives appear in different structures, nominal as well as verbal environments; all infinitives have verbal properties, in that they denote events (or states), as shown in (22). Syntactically, merging vo licenses the occurrence of the internal argument (when it is the case), as in (23). Morphologically, along the lines of Harris (1999), vo is responsible for projecting the verbal theme vowel (τ), appearing in all instances of infinitives, as in (24). This derivation is illustrated by the root √CANT in (25).

- (22)

- (a)

- O

- the

- cantar

- sing-INF

- dos pássaros

- of-the birds

- ao meio-dia (see o canto dos pássaros).

- at-the noon

- ‘the singing of the birds at noon’

- (b)

- Ao

- to-the-MASC

- cantarem

- sing-INF-AGR

- essa

- this

- música

- song

- ao

- at-the

- meio-dia…

- noon

- ‘by singing this song at noon…’

- (c)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Mary

- quer

- wants

- cantar

- sing-INF

- ao

- at-the

- meio-dia.

- noon

- ‘Mary wants to sing at noon’

- (23)

- (a)

- O

- the-MASC

- trocar

- switch-INF

- das

- of-the

- chaves (see a troca das chaves).

- keys

- ‘the switching of the keys’

- (b)

- Ao

- to-the-MASC

- trocar

- switch-INF

- as

- the

- chaves…

- keys

- ‘by switching the keys’

- (c)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Mary

- quer

- wants

- trocar

- switch-INF

- as

- the

- chaves.

- keys

- ‘Mary wants to switch the keys’

- (24)

- (a)

- O

- the-MASC

- narrar

- narrate-INF

- dos

- of-the

- fatos…

- facts

- ‘the narrating of the facts’

- (b)

- Ao

- to-the-MASC

- correr…

- run-INF

- ‘by running…’

- (c)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Mary

- quer

- wants

- dormir…

- sleep-INF

- ‘Mary wants to sleep’

- (25)

In (22) the occurrence of a time-locating modifier, ao meio-dia (‘at noon’), signals the event-reading of the nominal infinitive; hence, the presence of vo – in (22a), as well as in (23a). In (23) the examples show that the infinitives license the internal argument, as predicted.7 In turn, the data in (24) show the occurrence of the verbal theme vowel, associated to the verbal categorizer – in (25), vo projects τ,8 which will house the class morpheme, -a- for the root √CANT, which projects the internal argument.

Moreover, following Kratzer (1996), Distributed Morphologists have associated the licensing of the external argument to a different syntactic head, namely, Voice. As we can see in (26), if a (finite) verb licenses an external argument, then its infinitive form will as well. In turn, (27) shows that infinitives can occur with agent-oriented modifiers, as deliberado/deliberadamente (‘deliberate(ly)’), which is also treated as being a VoiceP’s property9 – see the representation in (30).

- (26)

- (a)

- O narrar

- the-MASC

- dos

- narrate-INF

- fatos

- of-the

- pela

- facts

- testemunha.

- by-the witness

- ‘the witnesses’ narrating of the facts’

- (b)

- O

- The

- João

- John

- misturar

- mix-INF

- drogas

- drugs

- com

- with

- álcool…

- alcohol

- ‘John’s mixing drugs and alcohol…’

- (c)

- A

- the-FEM

- testemunha

- witness

- tentou

- tried

- (ela mesma)

- (herself)

- narrar

- narrate-INF

- os

- the

- fatos.10

- facts

- ‘the witness tried to narrate the facts (herself)’

- (27)

- (a)

- O

- the

- narrar

- narrate-INF

- deliberado

- purposeful

- dos

- of-the

- fatos.

- facts

- ‘the purposeful narrating of the facts’

- (b)

- Misturar

- mix-INF

- propositadamente

- purposefully

- drogas

- drugs

- com

- with

- álcool…

- alcohol

- ‘purposefully mixing drugs and alcohol…’

- (c)

- A

- the

- testemunha

- witness

- tentou

- tried

- misturar

- mix-INF

- propositalmente

- purposefully

- drogas

- drugs

- com

- with

- álcool.

- alcohol

- ‘the witness tried to purposefully mix drugs and alcohol’

So far, we have shown that the three types of infinitives behave alike, regardless of Case-marking conditions – see footnotes 7 and 9. Along these lines, all infinitives are verbs. In Distributed Morphology, the system cannot look ahead and hence all properties must be the same until the point the derivation splits and the structure being formed gets its final categorization and, only then, assumes the different properties we observed in § 2 among verbal, nominal and mixed infinitives.

Following the literature on nominalizations (Alexiadou, 2001 and subsequent work), not only verbs can carry information about grammatical aspect (see (15)), but also nominals denoting events/states. Accordingly, we claim that infinitives (of all three types) contain AspP,11 whose head is crucial for the semantic interpretation of the events (§ 4), but also has syntactic and phonological reflexes, such as the co-occurrence with aspectual modifiers, constante(mente) (‘constant(ly)’) in (28) and the realization of Asp-morpheme, as in (29), for Polish – extracted from Alexiadou (2001, p. 131).

- (28)

- (a)

- O

- the-MASC

- constante

- constant

- bater

- ring-INF

- dos

- of-the

- sinos.

- bells

- ‘the constant bells’ ringing’

- (b)

- Ao

- to-the-MASC

- bater

- ring-INF

- constantemente

- constantly

- os

- the

- sinos…

- bells

- ‘by constantly ringing the bells…’

- (c)

- O

- the

- padre

- priest

- deseja

- wish

- bater

- ring-INF

- os

- the

- sinos

- bells

- constantemente.

- constantly

- ‘the priest wants to constantly ring the bells’

| (29) | (a) | Ocenianie studentów przez nuaczycieli ciagnęło się przez cały tydzień. |

| ‘evaluation-imperf students-gen by teachers lasted refl through the whole week’ | ||

| (b) | Ocenienie studentów przez nuaczycieli nastąpiło szybko. | |

| ‘evaluation-perf students-gen by teachers occurred quickly’ |

Even if the nominalizations in (29) are not infinitives (rather, “derived” nominals), these data provide evidence that Asp can have an independent morphophonological realization in event-nominals apart from its clearly outer-aspectual readings, such as in German infinitives (Alexiadou, Iordăchioaia & Schäfer, 2011). We come back to this issue later on.

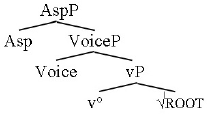

Regarding verbal infinitives, although the literature acknowledges that non-finite forms do not bear (T-)temporal properties – or, at least, they are temporally defective (Pires, 2006) – it has already been shown that they bear (outer-)aspectual properties: gerunds are durative (Rodrigues, 2006) and participles are perfective (Medeiros, 2010). Thus, built on this idea, we endorse the hypothesis that infinitives also contain AspP above VoiceP, as in (30).

- (30)

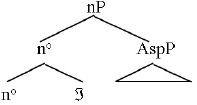

AspP is the last projection shared by all infinitives. As shown in § 2, nominal infinitives are prototypically nominals, in that they share all “external” properties with nouns (although they display the “internal” properties of verbs, such as event-reading, argument-structure, etc.) – see Brito (2013) for a similar conclusion. In this case, the nominal properties shown in § 2 are: precedence by determiners, nominal plural marking, modification by adjectives. All of these, along the lines of DM, are associated to no, the nominal categorizer. Moreover, following Harris (1999), further evidence for no is provided by the nominal theme vowel (ℑ) in (31), in the plural form of the nominal infinitive, as well as in (31b) for common nouns, and in (31c) for some derived words.

- (31)

- (a)

- falar-e-s,

- speak-TH-PL,

- dever-e-s,

- must-TH-PL,

- poder-e-s.

- can/may-TH-PL

- ‘the ways of speaking’, the duties, the powers’

- (b)

- altar-e-s,

- altar-TH-PL,

- os mare-s,

- sea-TH-PL,

- os sabore-s.

- flavor-TH-PL

- ‘the altars, the sea, the flavors’

- (c)

- mar-e-moto

- sea-TH-root

- ‘seaquake’

The nominal infinitive shares up to the nP-level the underlying form (that is, the same functional heads) with other event-nominalizations, as shown in (32) for affixal nominalizations in addition to (32a) and (23a) zero-affixed nominalizations. Therefore, in our analysis, /R/ is the realization of the no head – see Raposo (1987b) for a similar conclusion. The derivation of the nominal infinitive is represented in (33).

- (32)

- (a)

- A

- the-FEM

- narração

- narration

- dos

- of-the

- fatos

- facts

- pela

- by-the

- testemunha.

- witness

- ‘the narration of the facts by the witness’

- (a’)

- O

- the-MASC

- narrar

- narrate-INF

- dos

- of-the

- fatos

- facts

- pela

- by the

- testemunha.

- witness

- ‘the narrating of the facts by the witness’

- (b)

- O

- the-MASC

- nascimento

- born-ment

- de

- of

- uma

- a

- Nova

- new

- Era.

- era

- ‘the raise of a New Era’

- (b’)

- O

- the-MASC

- nascer

- born-INF

- de

- of

- uma

- a

- Nova

- new

- Era.

- era

- ‘the raising of a New Era

- (33)

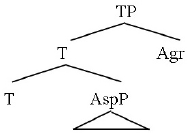

On the other hand, verbal infinitives are prototypically verbs – as shown in § 2 –, since they allow for the inflected-infinitive, modification by adverbs and assignment of accusative Case to the complement. Structurally, along the lines of the template in (15), above AspP, verbal infinitives have TP. As shown in § 2, this conclusion is borne out by the assignment of nominative Case to the subject, licensing of TP-adverbs and hosting of clitic pronouns.

Thus, as represented in (34), verbal infinitives do not have no, rather, they have T and then, /R/ is the realization of the TP/AspP-morpheme.12 Additionally, following Embick & Noyer (2007) and others, Agr (responsible for the agreement) is projected by T in MS (Morphological Structure), as well as the theme vowels by the categorizer heads. Thus, the template in (15), in our analysis, appears in verbal infinitives as in (35).

- (34)

| (35) | Verbal template in Portuguese (DM’s version): |

| √root + τ + vo (+ Voice) + Asp + T (+ Agr) |

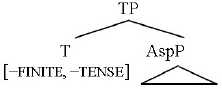

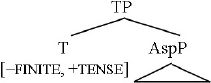

As shown in § 2, the verbal projections in (34) – as the template in (35) – underlie(s) all (morphologically) verbal infinitives. They can trigger (at least) two different readings: anaphoric and futurate. Additionally, mixed infinitives have another (and independent) tense-interpretation (following Landau, 2004)13 as we will show below. In any case, the different temporal values are not a matter of structure; rather, they are the outcome of different T-features. Thus, following Stowell (1982) and Landau (2004), we propose that the futurate reading is coded by T[+tense] and the anaphoric by T[–tense]. The idea is that the futurate reading, being future-oriented, is actually tense-marked.

Thus, we keep the same structure (i.e., projections) for all instances of verbal infinitives, despite of their different readings, which are captured by the specification of T. Furthermore, some device in the grammar must distinguish the infinitive tensed-T from the finite tensed-T one. Hence, assuming Stowell (1982) and others, we propose that in addition to tense, T has also a feature for finiteness. Thus, T[–finite] codes infinitive forms and T[+finite] finite forms. In this manner, we provide structures for anaphoric infinitives in (36a), exemplified in (16b), (17b) and (18b), and for the futurate infinitives in (36b), examples in (16a), (17a) and (18a).

- (36)

- (a)

- (b)

In this system, we can handle the different specification of T by means of a strict relation with the matrix sentence, for instance: if a verb (i.e., √/vP/VoiceP) is futurate-oriented, like prometer (‘promise’), or desiderative, like querer (‘want’), we will have a futurate reading for the embedded TP; if it is an implicative verb (manage-type) or the verb parecer (‘seem’) we will have an anaphoric reading. As for ECM-contexts, if it is a perception-verb as ver (‘see’) and ouvir (‘hear’), it will be anaphoric, but it will be futurate with causatives, like fazer (‘make’), or permissives, like deixar (‘let’) – see Cyrino & Sheehan (2018) for related ideas.

| (37) | (a) | If V (√/vo/Voice) is α, then T is [+TENSE]. |

| Where α = future-oriented verbs, desiderative verbs… | ||

| (b) | If V (√/vo/Voice) is β, then and T is [–TENSE]. | |

| Where β = parecer-type, implicative verbs… | ||

| (c) | If V (√/vo/Voice) is γ, then T can be [±TENSE]. | |

| Where γ = sensorial verbs, causative verbs… |

At last, mixed infinitives – as argued in § 2 – are verbs, in that they rely on the structure of verbal infinitives, given in (34) and (35), because, as shown, they exhibit all the properties associated to TP. Still, they are preceded by overt determiners and need to appear in Case-marked positions, supporting the analysis that these TPs must be headed by D. Thus, the remaining question is: if mixed infinitives have TPs, rather than nPs, which is the T-feature specification in this case?

It is noteworthy that under the analysis that the embedded infinitive/TP is either anaphoric or futurate in relation to the matrix finite verb, the value of the embedded T is determined in relation to the c-commanding-T, that is, the T heading the matrix clause. Thus, either the embedded T denotes future in relation to the higher T (Wurmbrand, 2014) conveying a futurate reading or the lower T denotes simultaneity in relation to the T-commanding T, triggering the anaphoric reading (Landau, 2004). Ultimately, the open specification of the lower T depends on the c-command relation to a higher T – see Kratzer (1998). However, as shown in (38), the so-proposed mixed infinitives usually appear in sentences not c-commanded by another T, as in complements of prepositions in (38a) and subjects in (38b)–(38c) – see also Raposo (1987a) and Modesto (2007).

- (38)

- (a)

- Ao abrir este site,

- to-the-MASC open-INF this site,

- você permitirá a exibição

- you allow-FUT

- de anúncios.

- the exhibition of pop-ups

- ‘by opening this website, you will allow for pop-ups’

- (b)

- Tocar

- play-INF

- violão

- guitar

- diverte

- amuses

- a

- the

- Maria.

- Mary

- ‘playing the guitar amuses Mary’

- (c)

- O

- the-MASC

- João

- John

- tocar

- play-INF

- violão

- guitar

- diverte

- amuses

- a

- the

- Maria.

- Mary

- ‘John’s playing the guitar amuses Mary’

Hence, given the data in (38), if the working hypothesis is on the right track, we predict that when mixed infinitives appear in non-embedded sentences, that is, when there is no c-commanding T, neither anaphoric nor futurate reading is available – given their syntactic conditioning. Thus, we propose that when the T-specification fails, the grammar will assign T an underspecified value, which we code as T[ ] – in the spirit of the “independent tense” from Landau’s (2004) system. We leave specific syntactic issues (such as control versus raising, etc.) for further research.

Thus, we explain in a step-by-step derivation the three Portuguese infinitives. Up to AspP-stage, all infinitives have the same derivational path, which explains their verbal-internal behavior and also their aspectual flavor, as we show in § 4. Later, however, above AspP, the grammar will split them off into nominal infinitives, by merging no and verbal infinitives, by merging T.

Then, if the so-generated TP (the infinitive-clause) is embedded, it will receive a temporal-dependent reading (anaphoric or futurate), but if the TP(-clause) appears as a subject or embedded in a PP, it will receive a non-dependent reading. Descriptively, these temporal-independent infinitives fall into what we called “mixed infinitives” and this is a matter we will explore in § 4, where we claim that TP/infinitives that are introduced by (prepositioned) determiners or occur as subjects do not present the usual tense-relation to the matrix clause, when TP/infinitives are embedded; for instance, in (38b)–(38c), the “generic” reading underlying tocar violão (‘play the guitar’) does not seem to convey a temporal reading, in the same way the sentences in (16)–(18) do.

In addition to their semantics, we highlighted that some infinitives/TP-clauses can be mixed in the sense that they exhibit nominal properties, as in (8)–(10), when there is an overt D, and perhaps in (11)–(14), where they display nominal properties, but do not display overt DPs. However, the discussion on the (non-overt) projections introducing TP-clauses is a topic that goes beyond our purposes – but see Resende (2021) for a proposal. For what matters here, mixed infinitives, when embedded, will obey the algorithm in (37), and the question on the functional projection introducing them (DP, CP, etc.) is an orthogonal one.

4. The semantics of infinitives

This section presents a proposal for the semantics of the “subatomic” ingredients of the infinitive structures described in § 3. In consonance with the Distributed Morphology framework, we assume for simplicity that a root is an index associated with a set of phonological instructions (in List 2) and encyclopedic knowledge (in List 3); these roots are acategorial and hence carry no grammatical content. Following Embick & Marantz (2008), the root is not interpretable (or pronounceable) before it is categorized. Based on these assumptions, apart from where the phrase cantar La Traviatta (‘to sing La Traviatta’) appears, its core meaning is given in (39c) – with (39b) being a simplified version of (25).

| (39) | (a) | cantar La Traviatta. |

| (b) | [v [√cant DP]]vP | |

| (c) | [[vP]]g,c = λw.λev. [cantar (ev) in w ∧ Theme (ev, a)]. |

When √cant is merged with vo, it becomes grammatically interpreted as a verb (although the encyclopedic knowledge comes into play only after spell out). It is projected as the set of events of singing (with its internal argument). The [√cant DP] denotes the set of all events of singing in all possible worlds; that is, the intension of singing – type <s<ev, t>>, where “ev” stands for eventualities (events and states). In (39a), the denotation of the DP is the individual denoted by La Traviatta, i.e., in (39c) the denotation of vP is the set of all singing events of La Traviatta, represented by a.

The next move is the introduction of the external argument via projection of Voice, as is current in the literature since Kratzer (1996) – (40b) is a simplified version of (30). Voice introduces the external argument; in the case of cantar, the agent. Thus, the VoiceP cantar dos pássaros (‘the birds’ singing’) denotes all events of singing performed by os pássaros (‘the birds’). For simplicity, we assume that a in (40c) is a plural individual.

| (40) | (a) | cantar dos pássaros. |

| (b) | [Voice [v [√cant DP]]vP]VoiceP | |

| (c) | [[VoiceP]]g,c = λw.λev [cantar (ev) in w ∧ Agent (ev, a)] |

Additionally, in § 3, we argued that all infinitives – nominal, verbal and mixed – project Asp. Although Resende (2020) claims that infinitives in Portuguese (with few exceptions) are imperfective, the examples in (41) – (a) from Brito (2013) and (b) from Oliveira (2014) – suggest otherwise.

- (41)

- (a)

- Os

- the

- meninos

- boys

- tornaram

- come-back

- a

- to

- sair mais

- leave-inf

- cedo

- early

- da sala

- from

- de

- the

- aula.

- classroom

- ‘the boys left early from the classroom again’

- (b)

- Ao

- to-the

- ganhar

- win-inf

- a

- the

- corrida,

- race,

- o

- the

- João

- John

- tornou-se

- became

- no

- the

- atleta

- athlete

- com

- with

- mais

- more

- vitórias.

- victories

- ‘by winning the race, John became the athlete with more victories’

The infinitive-verbs in (41) are achievements; it means that they are instantaneous. Although it is not our focus in this paper, the possibility of combining the infinitive with the past participle conveying the idea of completion of the event testifies for perfective interpretations. The contradiction in (42b) makes it clear that the event is interpreted as closed. However, the infinitive is also compatible with an imperfective reading. Telic predicates in the imperfective give raise to the imperfective paradox, i.e., they do not entail the completion of the event, as we show in (42a) and (43).

- (42)

- (a)

- Era

- was

- esperado

- expected

- o

- the

- João

- John

- morrer,

- die-inf,

- mas

- but

- ele

- he

- não

- not

- morreu.

- died

- ‘it was expected for John to die, but he did not’

- (b)

- *Era

- was

- esperado

- expected

- o

- the

- João

- John

- ter

- have-inf

- morrido,

- died,

- mas

- but

- ele

- he

- não

- not

- morreu.

- died

- ‘it was expected for John to have died, but he has not’

- (43)

- (a)

- O

- the

- menino

- boy

- atravessar

- cross-inf

- a

- the

- rua

- street

- levou

- led

- ao

- to-the

- seu

- his

- atropelamento.

- hitting

- ‘the boy’s crossing the street led to his hitting’

- (b)

- O

- the-masc

- atravessar

- cross-inf

- da

- of-the

- rua

- street

- pelo

- by-the

- menino

- boy

- levou

- led

- ao

- to-the

- seu

- his

- atropelamento.

- hitting

- ‘the boy’s crossing of the street led to his hitting’

In (42a), the telos provided by the achievement-predicate morrer (‘die’) is not reached, since the following sentence denies it without engendering a contradiction. Hence, the event has not culminated, differently from (42b) with a perfective predicate (in this case, the participle). The same pattern is found in (43) with the accomplishment-predicate atravessar a rua (‘cross the street’). In both sentences, the boy has not crossed the street, although he was crossing it when the hitting happened. Therefore, although there is an Asp-projection, infinitives cannot be always imperfective.

As regards the aspectual information coded by non-finite forms in Portuguese, the non-finite forms of the verb may be described as forming a system: the past participle (-d-) conveys perfectiveness, as in (44a), and the gerundive form (-nd-) seems to be specialized for progressiveness.

- (44)

- (a)

- O

- the

- João

- John

- ter

- have-inf

- atravessado

- crossed

- a

- the

- rua

- street

- sozinho

- alone

- assustou

- scared

- a

- the

- sua

- his

- mãe.

- mother

- ‘John’s having crossed the street by himself scared his mother’

- (b)

- O

- the

- João

- John

- estar

- be-inf

- atravessando

- crossing

- a

- the

- rua

- street

- sozinho

- alone

- é

- is

- um

- a

- perigo.

- danger

- ‘John’s crossing the street by himself is dangerous’

In all three types of infinitives detected in § 2, the aspect can be either imperfective or perfective. It might be constrained by the aspectual class of the verbs, as suggested by Oliveira (2014). For instance, in João acabou de ler o livro (‘John has just read the book’), the verbal infinitive has to be interpreted as perfective, since the time of the event is closed. Thus, following Rodrigues (2006), the specification of the aspect of infinitives might be dependent on the matrix sentence, in the same way tense-specification is.

In the literature, “aspect” is understood as the relation between the time of the event and the time of reference, which is then interpreted in relation to the utterance time. Here we adopt Klein’s (1994) proposal of time-coding in natural language and assume a distinction among perfective, imperfective and perfect. Furthermore, we assume that Asp introduces a time-interval with respect to which the event is related without specifying what is the relation; ultimately, a structure can have an Asp head without specifying in the syntax if its value is perfective, imperfective, etc.

For example, in (45), the verbal predicate is an activity, whereas in (46), it is an achievement. Thus, for (45a), the aspect is imperfective, whereas in (46a) it is perfective. This is supported by the data in (47) – whether acordar (‘awake’) has an experiencer or an agent is not crucial for our analysis.

| (45) | (a) | cantar dos pássaros. |

| (b) | [Asp [Voice [v [√cant DP]]vP]VoiceP]AspP | |

| (c) | [[AspP]]g,c = λw. λi. ∃(ev) (cantar (ev) in w ∧ Agent (ev, a) ∧ i ⊆ ev). |

| (46) | (a) | acordar do João. |

| (b) | [Asp [Voice [v [√acord DP]]vP]VoiceP]AspP | |

| (c) | [[AspP]]g,c = λw.λi.∃(ev) (acordar (ev) in w ∧ Experiencer (ev, j) ∧ i ⊇ ev) |

- (47)

- (a)

- O

- the

- cantar

- sing-inf

- dos

- of the

- pássaros

- birds

- [por/*em]

- [for/ *in]

- mais

- more

- de

- than

- duas

- two

- horas.

- hours

- ‘the bird’s singing for more than two hours’

- (b)

- O

- the

- acordar

- awake-inf

- do

- of-the

- João

- John

- [em/*por]

- [in/*for]

- duas

- two

- horas.

- hours

- ‘John’s awakening in two hours’

AspP denotes the set of times with respect to which there is at least one event of the sort denoted by the stem: the set of events of singing by the birds and the set of times with respect to which there was at least one awakening by João. Again, it is not the aim of this paper to go deep into the derivations; rather, it is to show the core meaning of all three infinitives. The first bifurcation happens when/if no is projected as in (48b), a simplified version of (33). For nominal infinitives as cantar dos pássaros, we propose that no shifts the predicate of intervals of time into a predicate of events, as shown in (48c).

| (48) | (a) | cantar dos pássaros. |

| (b) | [n [Asp [Voice [v [√cant DP]]vP]VoiceP]AspP]nP | |

| (c) | [[nP]]g,c = λw. λi. λev (cantar (ev) in w ∧ Agent (ev, a) ∧ i ⊆ τev). |

Later in the derivation, we assume that the definite article o (‘the-masc-sg’) corresponds to the ι operator. It restricts the predicate of event to the only one relevant in the context, as roughly represented in (49c).

| (49) | (a) | O cantar dos pássaros. |

| (b) | [D [n [Asp [Voice [v [√cant DP]]vP]VoiceP]AspP]nP]DP | |

| (c) | [[DP]]g,c = λi. ιev (cantar (ev) in w ∧ Agent (ev, c) ∧ i ⊆ τev) |

Thus, (49) is the particular event of singing by the birds which is happening with respect to a time interval i that will be assigned a value when it is combined with the verb as in o cantar dos pássaros me acordou (‘the birds singing woke me up’) where the singing by the birds includes the awakening.

If no is not projected, then T is, and we arrive at the structure in (34), simplified in (50b). As argued in § 3, this structure is common to both mixed and verbal infinitives. Here the working hypothesis is that T introduces information about finiteness and tense (Stowell, 1982). As regards tense, the system opposes the tense-marked forms, T[–finite, ±tense], (in this case, anaphoric or futurate) to T[–finite, tense[ ]], where tense[ ] means that it is tenseless. We propose that semantically the lack of tense-specification shifts the predicate of intervals of time into a predicate of events, resulting in the same denotation as the nominalizer. It is noteworthy that given the absence of a T-value, since until AspP, as argued, all infinitives are alike, there would be no grammatical/semantic ingredient responsible for providing a logical form different from (48c), when a T[ ] is merged.

The lack of tense-specification, T[ ], abstracts the event argument as a last resort operation to prevent the derivation from crashing, and we end up with a property of events like the n-denotation in the nominal derivation. Thus, the ɩ operator may apply and the result for (50a) in (50c) is: there is one and only one event of singing performed by the birds which was in course at the contextually relevant reference time; such an event woke up the speaker. Thus, the truth conditions are exactly the same, as we see in (49c) and (50c).14

- (50)

- (a)

- Os

- the-masc-pl

- pássaros

- birds

- cantarem

- sing-inf-agr

- (me acordou).

- (me woke up)

- ‘the birds’ singing woke me up’

- (b)

- [D [T [Asp [Voice [v [√root DP]]vP]VoiceP]AspP]TP]DP

- (c)

- [[TP[ ]]]g. c = λw. λi. ιev (cantar (ev) in w ∧ Agent (ev, a) ∧ i* ⊆ τev)

We now move to our last structure, where T is [–finite] and the tense is valued, that is, T[±tense]. These are complex syntactic structures and, again, it is beyond the scope of this paper to give a full-fleshed derivation, taking into account all the syntactic issues that are relevant for solving this puzzle. In § 3, we argued that the difference between the futurate and the anaphoric readings correlates to the “+” and “–” values of T. We also proposed an analysis based on the matrix-sentence: verbs like tentar (‘try’) requires T[–tense], whereas querer (‘want’), T[+tense]. Thus, T relates the reference time of the AspP to referential pro-forms, as suggested in Partee (1973).

We propose that T[+tense] codes the reference interval as futurate in relation to the tensed-T of the matrix (finite) verb – see also Abusch (2004) and Wurmbrand (2014). In turn, we claim that T[–tense] means that the tense of the embedded clause is anaphoric (a relative “now” in Wurmbrand’s (2014) system), where the matrix predicate imposes the reference time to the embedded infinitive. Thus, tense relates the reference time with respect to the matrix clause (Landau, 2004) and it is also somehow underspecified, as in (51) by i R i*, where i* is the c-commanding tensed-TP.

| (51) | [[TP[±tense]]]g.c = λi. ∃(ev) (stem (ev) in w ∧ Agent (ev, a) ∧ i R ev ∧ i R i*) |

If T is [–tense], then the reference time is related to the anchor-time given by the matrix, which includes trying and being successful. Thus, the event of singing in (52a) is interpreted as past with respect to the utterance and simultaneous with being successful, as represented by the logical form in (52b) – with other projections omitted.

- (52)

- (a)

- O

- the

- João

- John

- conseguiu

- got

- [TP cantar].

- sing-inf

- ‘John managed to sing’

- (b)

- [[TP cantar]]g.c = past1 … t1 cantar (ev) ∧ τev ⊆ t1

Informally, the effort to achieve the goal of singing is in the past, as well as the achievement of the goal of singing. Thus, in all the worlds in the past where John tried and succeeded, there is at least one event of his singing. Desiderative verbs as querer may be semantically treated as a relation between an individual and the content of his/her desire; with [+tense] meaning “futurate”, then it assigns a value to R, as we see in (53b), and (53c) – with other details omitted.

- (53)

- (a)

- O

- the

- João

- John

- quis

- wanted

- [TP brincar].

- play-inf

- ‘John wanted to play’

- (b)

- [[TP brincar]]g.c = past 1 … t1 brincar (ev) ∧ i2 ≥ i0

In short, in this section we presented a compositional account for the three types of infinitives described in § 3. The core of the infinitives is the same up to AspP. When the system comes to Asp, our working hypothesis is that, differently form participles and gerunds, infinitives are underspecified, and the aspectual relation will be determined later in the derivation, in relation to the matrix sentence. After AspP, the system will merge no or T. In the later case, if the infinitive-clause is embedded in a T(ensed)-sentence, it will assume a [±tense], depending on the matrix verb. Otherwise, the T head will not have a projection from which to obtain its value, then T will remain underspecified. Semantically given the lack of tense, as we propose, the grammar will apply an operation that shifts the predicate of intervals of time into a predicate of events. This happens for both nominal (when no is merged) and mixed infinitives (when there is a T[ ]).

5. Outlook and conclusion

In this paper we proposed a morphosyntactic and semantic derivation for the three types of infinitive found in the literature about Portuguese. First, in § 2, we showed that morphologically (that is, as regards their internal structure), infinitives can be nominal (with no) and verbal (with T). Additionally, we argued that nominal infinitives syntactically behave just like other types of nominalization. In turn, verbal infinitives can be either prototypically verbs or “mixed” in that they appear inside DPs, just like other nominals, what assigns them a “hybrid character”.

In § 3, we showed that these three types of infinitives have the same derivation up to AspP, where the first bifurcation distinguishes nominal infinitives, when no is merged, from verbal infinitives, when T is projected. We argued that AspP is underdetermined in infinitives, differently from the other non-finite forms. Moreover, we argued that T may have three values, namely, T[+tense], T[–tense] and T[ ]. With T[ ], the lack of tense(-feature) changes the phrase into a predicate of events, as a last resort operation. The result is that mixed and nominal infinitives are truth-conditionally equivalent. Additionally, prototypical verbal infinitives spilt off in T[+tense] and T[–tense], which will be responsible for coding the futurate and the anaphoric reading, respectively.

In § 4, we proposed a compositional semantics for these morphosyntactic structures. We are aware that many syntactic and semantics issues remain open. Some of them were overlooked due to the scope; others, because they require further investigation. Still, we believe that this paper introduces a proposal that, at least tentatively, explains the three most common types of Portuguese infinitives, and more importantly: what relates them, by showing what they have in common and where they come apart.

Notes

- We are very thankful to the Journal of Portuguese Linguistics reviewers for all very helpful comments and suggestions – even if we could not properly respond to all the observations in this paper. We also thank to CNPq for financially supporting the scholarship of Roberta Pires de Oliveira, PQ-ID 303555/2016-5. [^]

- This observation has to do with the fact that, in non-standard dialects of BP – also in language acquisition – in most of the occurrences, the infinitive is identified by the stressed final (verbal theme) vowel. Hence, the idea is that there would be no /R/-elision in these contexts, but rather an /R/-epithesis in dialects where /R/ is realized – see Nunes (2015), Resende (2016, 2020), and Schwindt & Chaves (2019) for discussion. [^]

- There is also a coincidence, in the phonological form of infinitives and regular verbal forms from the future subjunctive – e.g. quando eu falar (‘when I will speak’) –, but the discussion of these forms is not under the scope of the present analysis – see Nunes (2015) and Resende (2020). [^]

- One anonymous reviewer noted that there seems to be a syntactic difference between dever and poder, on the one hand, and prototypical nominal infinitives on the other, such as plurality, i.e., whereas the so-called “lexicalized infinitives” accept plural marking, as in (2), other nominal infinitives seem to reject it. Following Alexiadou, Iordăchioaia & Soare (2010), this can be associated to the kind of reading the infinitive triggers; for these authors, perfective (usually, count) are compatible with pluralization, whereas imperfective readings (usually, mass) reject it. Our underspecified analysis for infinitives has, thus, a further syntactic/semantic piece to deal with, but this is a topic that needs further investigation. [^]

- From Raízes do Brasil by Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (1936, p. 148). [^]

- See Gonçalves, Santos & Duarte (2014) and also Cunha & Silvano (2016) for an alternative account for this ungrammaticality – one against Landau’s (2004) system. [^]

- Here, we assume that the dummy preposition-insertion is a PF-requirement, which has to do with a last-resort mechanism to prevent the derivation from crashing, because of its Case-less status (Harley & Noyer, 1997), that is, when the structure is nominal. Again, this is not a crucial matter for presenting the argument – see Resende (2020) for analysis and discussion. [^]

- Actually, Harris’ (1999) proposal is that for every categorizer head in the syntax, a thematic position (th) is projected in Morphological Structure (MS), in the PF-branch – see also Embick & Noyer (2007). In any case, the point in (25) is just to show that the verbal theme vowel depends on vo. Therefore, we can omit further details. [^]

- Again, for simplicity, we leave aside some details, such as the Voice-specification, [pass]/[act], which could possibly handle both the Case-marking issue and the argument/adjunct distinction. In any case, the leading idea is that both passive-constructions and nominalizations would be specified as [pass] due to the non-obligatoriness of the external argument, differently from active-constructions. This alignment made some nominals being called “passive-nominalizations”. [^]

- It should be noted that the interposing ela mesma (‘herself’) in (26c) is only possible with prosodic focus and with mesma (‘self’), not just ela (‘her’). However, this example just meant to signal that the embedded infinitive narrar (‘narrate’) also contains Voice and however syntax handles this interposing, ela mesma can be seen as being licensed by the infinitive’s Voice. [^]

- Here, we leave aside the question of whether or not grammatical aspect-information should be coded as a (T-)feature or as an Asp projection and simply assume the current view that, as the nominalizations, there is an AspP above VoiceP, as in (30) – but see Resende (2020) for discussion and consequences and also Santana (2016) for an alternative view. [^]

- Just like any other inflected verbal form in Portuguese, as the traditional view’s template in (15) shows, the TA-morpheme (Tense/Aspect) is syncretic. For simplicity, we just assume that “Mood” is a feature associated only to finite forms. Therefore, /R/ is actually the realization of a T/Asp morpheme, not just TP. Being so, the grammar must manage to merge the morphemes in the verbal environment, allowing for them to realize a single node – see Resende (2020) for a proposal along these lines and Santana (2016) for an alternative view, both within DM. [^]

- But see Gonçalves, Cunha & Silvano (2010) and Gonçalves, Santos & Duarte (2014) for an alternative view, against Landau’s (2004). [^]

- We should mention that there might me a pragmatic/discursive difference between o cantar dos pássaros e os pássaros canterem; maybe the same kind of difference we observe at the opposition between passive- and active-constructions, which is an issue that we will not pursue any further. Additionally, just as in the opposition passive/active, we have syntactic consequences; in this case, the further merging of D, which seems to be needed in the nominal context, but only possible with (some) verbal/mixed infinitives. [^]

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Abusch, D. (2004). On the temporal composition of infinitives. In J. Guéron & J. Lecarme (Eds.), The syntax of time (pp. 27–53). Cambridge: MIT.

Alexiadou, A. (2001). Functional structure in nominals: nominalization and ergativity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.42

Alexaidou, A., Iordăchioaia, G., & Schäfer, F. (2011). Scaling the variation in Romance and Germanic nominalizations. In P. Sleeman & H. Perridon (Eds.), The noun phrase in Romance and Germanic: structure, variation and change (pp. 25–40). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.171.04ale

Alexaidou, A., Iordăchioaia, G., & Soare, E. (2010). Number/aspect in the syntax of nominalizations. Journal of Linguistics, 46, 537–574. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226710000058

Ambar, M. (2000). Infinitives versus participles. In J. Costa (Ed.), Portuguese syntax: new comparative studies (pp. 14–30). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Basílio, M. (1987). Teoria lexical [Lexical Theory]. São Paulo: Ática.

Bošcović, Ž. (1996). Selection and the categorial status of infinitival complements. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 14, 269–304. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00133685

Brito, A. M. (2013). Tensed and non-tensed nominalization of infinitive in Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 12(1), 7–40. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.75

Camara, J. M., Jr. (1970). Estrutura da língua portuguesa [Portuguese language structure]. (40th ed.). Petrópolis: Vozes.

Chierchia, G. (1985). Formal semantics and the grammar of predication. Linguistic Inquiry, 16(3), 417–443.

Chomsky, N. (1970). Remarks on nominalization. In R. Jacobs & P. Rosenbaum (Eds.), Readings in English transformational grammar (pp. 184–221). Waltham: Ginn and Company.

Cyrino, S., & Sheehan, M. (2018). Why do some ECM verbs resist passivization? A phase-based explanation. Proceedings of NELS.

Demonte, V., & Varela, S. (1997). Spanish event infinitives: form lexical semantics to syntax-morphology. Proceedings of 21st Incontro di Grammatica Generativa 1995 (pp. 145–169), Milan.

Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2007). Distributed Morphology and the morphology-syntax interface. In G. Ramchand & C. Reiss (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces (pp. 289–324). Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199247455.013.0010

Embick, D., & Marantz, A. (2008). Architecture and blocking. Linguistic Inquiry, 39(1), 1–53. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2008.39.1.1

Ferreira, M. (2020). Alçamento temporal em complementos infinitivos do português [Temporal raising in Portuguese infinitival complements]. Cadernos de Estudos Linguísticos, 62(1), 1–19. DOI: http://doi.org/10.20396/cel.v62i0.8655883

Gonçalves, A., & Costa, T. (2002). (Auxiliar a) compreender os verbos auxiliares [(To auxiliate) to understand auxiliary verbs]. Lisboa: Edições Colibri.

Gonçalves, A. B., Cunha, L. F., & Silvano, P. (2010). Interpretação temporal dos domínios infinitivos na construção de reestruturação do português europeu [The interpretation of the temporal domains in European Portuguese restructuring constructions]. In Brito, A. M. et alli (Eds.). Textos selecionados do XXV Encontro Nacional da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística (pp. 435–447), Lisboa.

Gonçalves, A., Santos, A. L., & Duarte, I. (2014). (Pseudo-)inflected infinitives and control as Agree. In K. Lahousse & S. Marzo (Eds.). Selected papers from Going Romance (pp. 161–180), Leuven 2012. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/rllt.6.08gon

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). A Morfologia Distribuída e as peças da flexão [Distributed Morphology and the pieces of inflection]. Curitiba: UFPR, 2020.

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1994). Algumas características centrais da Morfologia Distribuída [Some key features of Distributed Morphology]. Revista do GELNE, 22(2), 418–429, 2020. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21680/1517-7874.2020v22n2ID23286

Harley, H., & Noyer, R. (1997). Mixed nominalizations, short verb movement and object shift in English. In P. N. Tamanji & K. Kusumoto (Eds.), Proceedings of 28th North East Linguistic Society (pp. 143–157). Amherst.

Harris, J. (1999). Nasal depalatalization no, morphological well-formedness si: the structure of Spanish word classes. MIT Working papers in Linguistics, 33, 47–82.

Iordăchioaia, G. (2013). The determiner restriction in nominalizations. Proceedings of Workshop languages with and without articles (pp. 1–14). Paris.

Klein, W. (1994). Time in language. London: Routledge.

Kratzer, A. (1996). Severing the external argument from its verb. In J. Rooryck & L. Zaring (Eds.), Phrase structure and the lexicon (pp. 109–137). Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8617-7_5

Kratzer, A. (1998). More structural analogies between pronouns and tenses. Proceedings of 8th Semantics and Linguistic Theory (pp. 92–110). Amherst. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v8i0.2808

Landau, I. (2004). The scale of finiteness and the calculus of control. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 22, 811–877. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-004-4265-5

Lunguinho, M. V. S. (2006). Dependências morfossintáticas: a relação verbo-auxiliar-forma nominal [Morpho-syntactic dependences: the auxiliary verb-nominal form relation]. Revista de Estudos Linguísticos, 14(2), 457–489. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17851/2237-2083.14.2.457-489

Martin, R. (2001). Null Case and the distribution of PRO. Linguistic Inquiry, 32(1), 141–166. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/002438901554612

Medeiros, A. (2010). Aspecto e estrutura de evento nas nominalizações do português do Brasil: revendo o caso das nominalizações em -ada [Aspect and event-structure in the Brazilian Portuguese nominalizations: revisiting the case of ada-nominalizations]. Letras de hoje, 81, 99–122. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5380/rel.v81i0.17318

Modesto, M. (2007). Inflected infinitives in Brazilian Portuguese as an argument both contra and in favor of a movement analysis of control. Letras, 72, 297–309. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5380/rel.v72i0.7553

Nunes, J. (2015). De clítico à concordância: o caso dos acusativos de terceira pessoa em português brasileiro [From clitic to agreement: the case of accusative pronouns of 3rd person in Brazilian Portuguese]. Caderno de Estudos Linguísticos, 57(1), 61–84. DOI: http://doi.org/10.20396/cel.v57i1.8641472

Oliveira, I. C. P. (2014). Usos verbais e nominais do infinitivo em português europeu [Verbal and nominal uses of infinitives in European Portuguese]. Master dissertation, Universidade do Porto, Lisboa.

Partee, B. (1973). Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns in English. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 601–609. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2025024

Pires, A. (2006). The minimalism syntax of defective domains: gerunds and infinitives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.98

Raposo, E. P. (1987a). Romance infinitival clauses and Case theory. In C. Neidle & R. A. N. Cedeño (Eds.), Studies in Romance languages (pp. 237–249). Dordrecht: Foris.

Raposo, E. P. (1987b). Case theory and Infl-to-compl: the inflected infinitive in European Portuguese. Linguistic Inquiry, 18(1), 85–109.

Resende, M. S. (2016). Por uma releitura das nominalizações em infinitivo do português [For a review of Portuguese infinitival nominalizations]. Caderno de Squibs, 2(2), 26–37.

Resende, M. S. (2020). A Morfologia Distribuída e as peças da nominalização: morfofonologia, morfossintaxe, morfossemântica [Distributed Morphology and the pieces of nominalization: morphophonology, morpho-syntax, morpho-semantics], PhD thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21165/el.v50i1.2891

Resende, M. S. (2021). Sobre a sintaxe da interpretação temporal dos infinitivos em português [On the syntax of the temporal interpretation of Portuguese infinitives]. Estudos Linguísticos, 50(1), 403–425. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21165/el.v50i1.2891

Rodrigues, P. A. (2006). O aspecto nas construções infinitivas e gerundivas complementos de verbo de percepção [The aspect of infinitival and gerundive constructions as complements of perception-verbs]. Revista de Estudos Linguísticos, 14(2), 77–98, 2006. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17851/2237-2083.14.2.77-98

Silvano, P., & Cunha, L. F. (2016). Sobre a caracterização temporal de frases complexas com orações adverbiais finais com ‘para’ em português europeu [On the temporal characterization of complex phrases with final adverbial-clauses with para (‘to’) in European Portuguese]. Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística, 10(2), 301–402. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21747/2183-9077/rapl2a17

Sleeman, P. (2010). The nominalized infinitive in French: structure and change. Linguística, 5, 145–173.

Schwindt, L. C., & Chaves, R. G. (2019). Convergências no processo de apagamento de /R/ em português e espanhol [Convergences on the deletion of /R/ in Portuguese and Spanish]. Lingüística, 35(1), 129–147. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5935/2079-312X.20190007

Stowell, T. (1982). The tense of infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry, 13, 561–570.

Wurmbrand, S. (2014). Tense and aspect in English infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry, 45(3), 403–447. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/LING_a_00161

Zucchi, A. (1993). The language of propositions and events: issues in syntax and semantics of nominalizations. Dordrecht: Kluwer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8161-5