1. Introduction

In the Portuguese grammar, Neves (2011, p. 106) defines proper names as “nomes específicos de pessoas (antropônimos), lugares (topônimos), datas, festividades, marcas de produtos, livros, revistas, peças, associações, agremiações, órgãos ou repartições etc.” (‘specific names of people (anthroponyms), places (toponyms), dates, festivities, product brands, books, magazines, plays, associations, clubs, organizational bodies or offices, etc.’). They are, therefore, expressions that refer to particular entities in opposition to common nouns.

Since Dionysus Thrax (2002, n.d.), in the 2nd century BCE, up to the present day, grammatical studies have contrasted proper names with common nouns on the basis of their semantic features: proper names apply to a single individual, and common nouns apply to a class of individuals. At the heart of this distinction is the notion that proper names have little or no descriptive content and are only used to refer to a specific individual, while common nouns have a meaning, so that they denote entities by providing them with an appropriate description.

Functional Discourse Grammar (FDG – Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2008) shares Lyons’s view that proper names “may have reference, but not sense, and they cannot be used predicatively purely as names” (Lyons, 1977, p. 219). Moreover, proper names are considered inherently identifiable units, and given their lack of lexical meaning, they cannot be semantically modified.

Although this approach does indeed cover most uses of proper names, it is not rare to find instances of proper names behaving differently. Keizer (2008) has proposed an alternative treatment within the FDG framework to account for proper names used ascriptively (e.g., in close appositions and in labelling sentences such as I am Peter). As for restrictive modification, Giomi (2020) proposes a new approach that does allow this sort of modifier with proper names. García Velasco (2009a,b), when discussing coercion in FDG, has also considered how proper names behave in this type of process. As each of these works deals with a specific phenomenon, FDG still lacks a comprehensive approach to proper names.

The aims of this paper are to describe the use of proper names in Portuguese and, based on the findings, to present an FDG view that is designed to account for most of its uses. The paper is organized into four further sections. Section 2 provides a brief account of proper names in philosophical and linguistic approaches; Section 3 presents the model FDG and its approach to proper names; Section 4 offers a description of proper names in Portuguese and presents an FDG analysis of each use found; Section 5 summarizes the findings.

2. A brief account of the reference and meaning of proper names

As mentioned earlier, proper names are usually defined in contrast to common nouns. These categorizations generally take into account that common nouns apply to any member of a class, while proper names are limited to the reference to a single entity.

For many philosophers, unique identification or unique reference is a feature that defines proper names. Mill (1868 [1843]) postulates that they apply only to the identification of people and objects, with no implication of any property being attributed to the individual referred to. In other words, the proper name is a word that indicates who or what we are talking about, but does not say anything else about the entity to which it refers. Mill (1868) also contrasts proper names with common nouns, on the basis that the latter are elements that communicate some type of information.

For Frege (1948 [1892]), the proper name not only has reference (Bedeutung), but sense (Sinn) as well, provided with a definite description. In the case of a proper name such as Aristotle, opinions may differ, as one can take as its sense the description Plato’s pupil or Alexander the Great’s teacher, although the reference remains the same. For this reason, Frege admits that there might be fluctuations regarding the sense of a proper name.

Russell (2010 [1918]) states that proper names are “truncated” or “abbreviated” descriptions. For this author, a name like Socrates, for example, was once used to refer to an object of direct knowledge. Since direct knowledge is no longer possible, the proper name becomes a truncated description for Plato’s teacher or the philosopher who drank the cup of poison.

Wittgenstein (1922) is of the opinion that the meaning of a proper name is the object itself. Later, however, Wittgenstein (1953) claims that to affirm that the thing itself is the meaning of a proper name is linguistically untenable, and goes on to defend the position that the meaning of the name is not the referent, but the descriptions that someone may give to the thing named. Searle (1969), in contrast, states that proper names are in fact not identifying descriptions, and that definitions are ascribed to the bearers of names and not to the names themselves.

As it is evident from this brief survey, authors have differed as to their understanding of proper names, and more specifically about whether they have meaning or not. In this regard, Jespersen (1924) states that proper names have meaning, since they make the listener think about a set of attributes, and, as a person’s name is identified, information about him/her is progressively added. The fact that they connote several attributes is, for Jespersen (1924), what allows proper names to be used as common names in structures such as “He is a Judas”.

Kripke (1980), on the other hand, maintains Mill’s idea that proper names are meaningless; in fact, he is of the opinion that they are rigid designators and are not related to attributes. To access the thing named, its description is not required, as it suffices that the name has been assigned to an individual and passed on from person to person. In this sense, the causal chains connect names to the referent, for which reason they become rigid.

A common feature of the definitions of proper names is that they are fundamentally referential. However, there is no consensus regarding the question of sense. On the one hand, Mill (1868) and Kripke (1980) argue that the name has no sense; on the other, Frege (1948), Russell (2010), Wittgenstein (1953), and Jespersen (1924) associate the sense of proper names with definite descriptions.

As in philosophy, all definitions of proper names in linguistics also have in common the idea that they are, by nature, referential expressions. According to Lyons (1977, p. 179), proper names constitute, together with definite noun phrases and personal pronouns, singular referential expressions, that is, expressions that refer to individuals and not to classes of individuals. Lyons’s (1977, p. 219) view is that proper names have no meaning, only reference, and cannot be used predicatively, thus distancing himself from the philosophical conceptualizations in Frege (1948), Russell (2010) and Jespersen (1924), discussed above.

In addition to these views which, in general, either maintain that the proper name has no meaning or associate the meaning of the proper name with definite expressions, there are authors, such as Kleiber (1981) and Katz (2001), who understand the proper name as a predicate, as in ‘X called Y’ or ‘X is a bearer of Y’. Metalinguistic theories of this sort have received criticism, as pointed out by Van Langendonck (2007), especially because they might apply to items that are not commonly understood as proper names.

In order to give a typologically acceptable conceptualization of proper names, Van Langendonck (2007, p. 7) proposes a distinction between “proprial” lemmas in isolation and proper names, the former being lexemes in their dictionary form, and the latter lexemes used as prototypical proper names. It is on the basis of this distinction that Van Langendonck explains the coercion process from proper names to common nouns (i.e., another John, that is another person with the name John). In such cases, the proprial lemma John functions as a common noun, as opposed to John arrived, in which the proprial lemma functions as a proper name, its most primary function. On this basis, the author offers the following definition of proper names:

“A proper name is a noun that denotes a unique entity at the level of established linguistic convention to make it psychosocially salient within a given basic level category [pragmatic]. The meaning of the name, if any, does not (or not any longer) determine its denotation [semantic]. An important formal reflex of this pragmatic-semantic characterization of proper names is their ability to appear in such close appositional constructions as the poet Burns, Fido the dog, the River Thames, or the City of London [syntactic].” (Van Langendonck, 2007, p. 87).

In addition to what is contained in this definition, Van Langendonck (2007, p. 72) argues that proper names have a presuppositional meaning. This means that whenever a proper name is used, there is a categorical presupposition of whether the referent is a male or female person, a country, a river, etc.

Moreover, the author claims that a proper name cannot be under the scope of restrictive modifiers, and because they are inherently definite,1 they are not accompanied by a definite article. Finally, a proper name does not refer back to another noun phrase (Np), as shown in (1), quoted from Van Langendonck (2007, p. 153):

- (1)

- (a)

- Napoleon was the Emperor of France. He lost at Waterloo.

- (b)

- He was the Emperor of France. Napoleon lost at Waterloo.

What stands out in Van Langendonck’s view on proper names is their occurrence in close appositions, such as the poet Burns. The author argues that such structures are crucial in defining proper names, since they show how closely the proper name is connected to its categorical meaning, as the poet Burns entails that Burns is a poet (Van Langendonck, 2007, p. 70). Although this relation between the semantics and the morphosyntax of a proper name is indeed valid, it would be difficult to neglect the role of pragmatics in such close appositions.

Previous studies in FDG (English: Keizer, 2007; Portuguese: Lemson, 2016; Serafim, 2019) show that, in close appositions such as the poet Burns (‘o poeta Burns’), both names are used ascriptively and only the noun phrase as a whole is used to refer. Thus, to assume that close appositions are crucial to defining proper names is inconsistent, because of the precedence of pragmatics over semantics and morphosyntax in FDG. This means that it is not possible to assume the alignment of an instance of ascription in close appositions and a proper name as a defining property of this noun class.

For the purpose of this paper, I assume, following Lyons (1977) and Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008), that proper names have reference, but not lexical meaning. The categorical presupposition present in Van Langendonck’s work can be broadly accounted for by means of the relevant variable at the Representational Level, indicating whether the proper noun is an individual, a time or a place. This will be dealt with in more detail in Section 3.2.

3. Functional Discourse Grammar

3.1. The architecture of the model

This work adopts the theoretical perspective of Functional Discourse Grammar (Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2008), a grammar model that has a top-down organization. The top-down architecture of the grammar is justified by the fact that a grammar model will be more effective the more its organization resembles linguistic processing within an individual (Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2008).

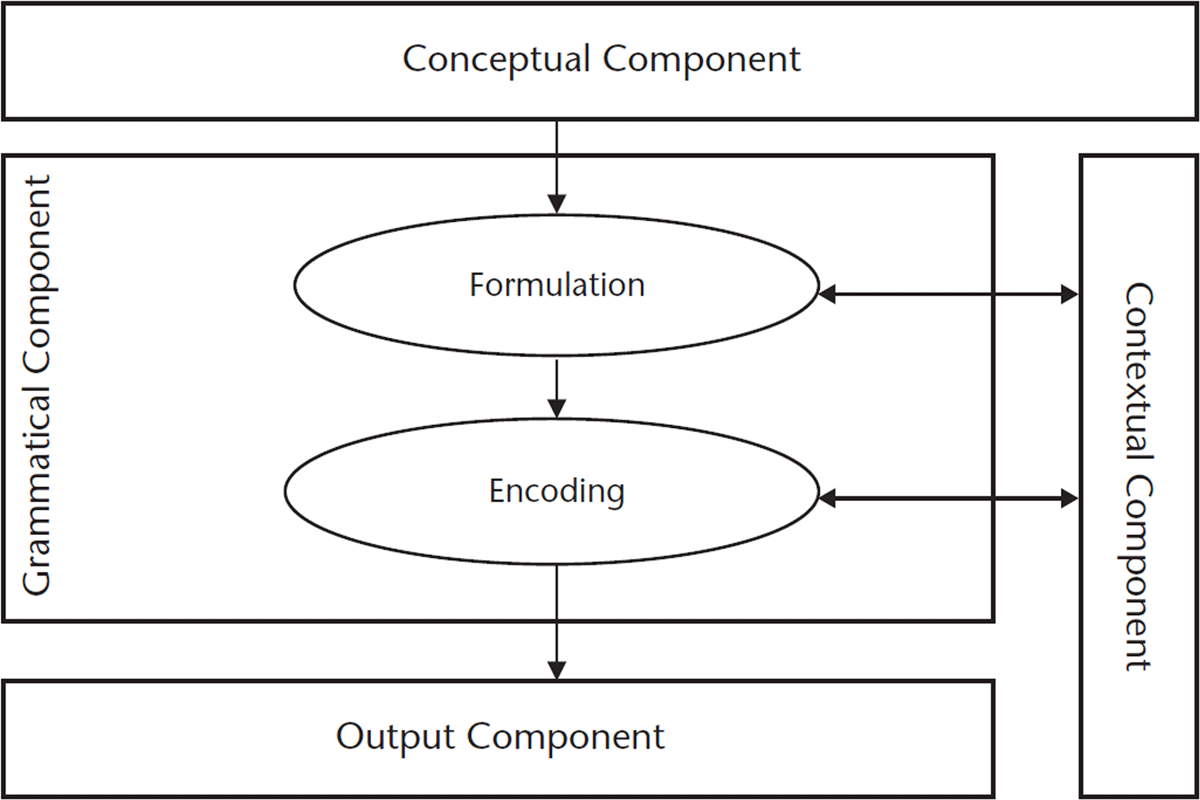

The FDG model consists of a Grammatical Component in a wider theory of verbal interaction in which the grammar interacts with three non-grammatical components: the Conceptual Component, the Output Component and the Contextual Component (see Figure 1).

FDG as part of a wider theory of verbal interaction (Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2008, p. 6).

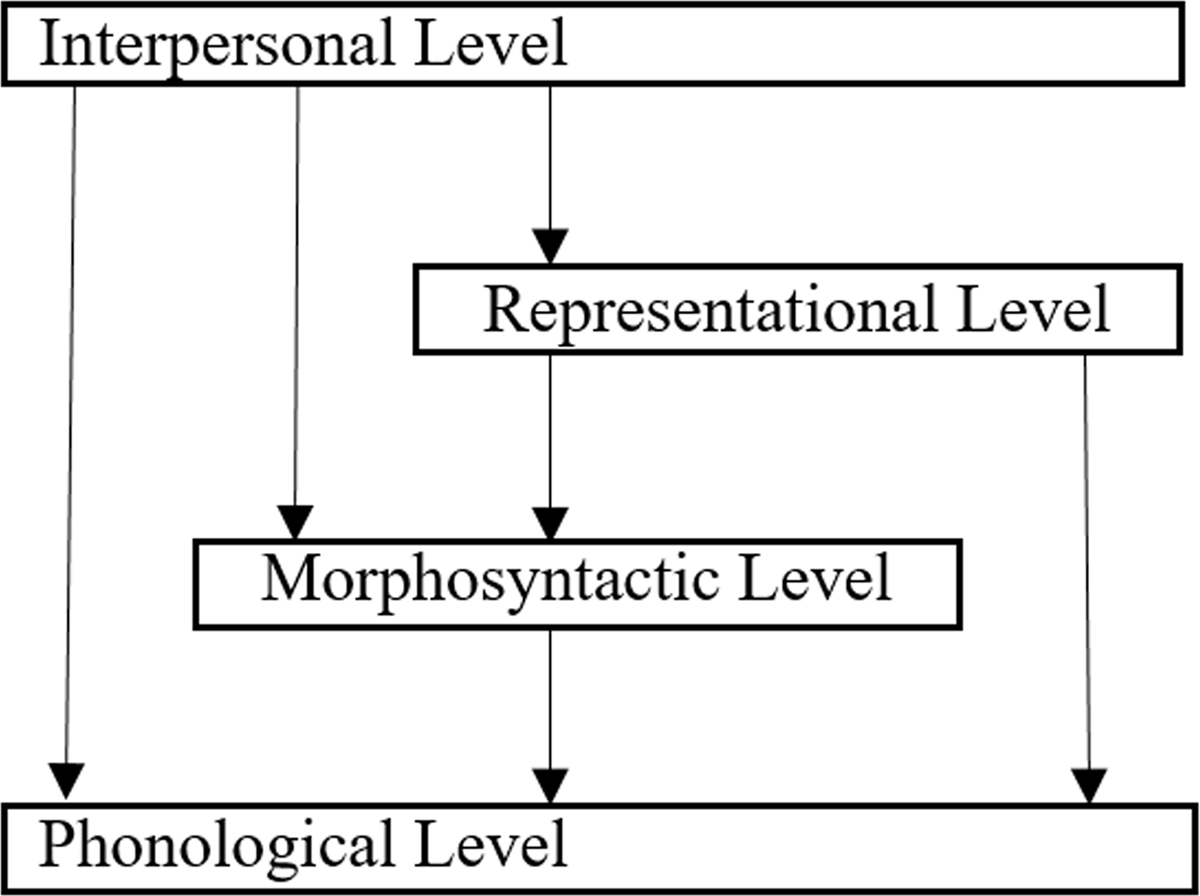

The Conceptual Component is responsible for the speaker’s communicative intention and the corresponding mental representations. The operation of Formulation converts these representations into pragmatic and semantic representations for the two highest levels, the Interpersonal and the Representational Level, respectively, within the Grammatical Component. The operation of Morphosyntactic Encoding converts pragmatic and semantic content into formal morphosyntactic units. The operation of Phonological Encoding converts the content of the Interpersonal, Representational and Morphosyntactic Levels into phonological units (see Figure 2 for the internal structure of the Grammatical Component). The Output Component generates acoustic, written, or signed expressions based on the information provided by the Grammatical Component. The Contextual Component interacts with all levels of representation, and it affects the operations of Formulation and Encoding.

The Grammatical Component includes four hierarchically structured levels of analysis, each composed of layers that may be in a hierarchical or non-hierarchical (configurational) relationship. The general structure of each layer is arranged as in (2), where v1, representing the variable of the relevant layer, is restricted by a head that takes the variable as its argument. The layer can be further restricted by a modifier (σ), specified by an operator (π) and may carry a function (Φ).

- (2)

- (π v1: [head (v1)Φ] : [σ (v1) Φ]) (Hengeveld & Mackenzie 2008, p. 15)

The Interpersonal Level (IL) is responsible the distinctions of formulation related to the interaction between speakers and addressees. The Representational Level (RL) takes care of designation and all semantic aspects of the grammar of a language. The Morphosyntactic Level (ML) and the Phonological Level (PL) deal with the formal aspects of a linguistic unit. The top-down FDG architecture shows that much of what happens in Morphosyntactic and Phonological Levels is motivated by the levels of Formulation, i.e., the Interpersonal and Representational Levels.

3.2. Proper names in FDG

3.2.1. Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008)

Hengeveld and Mackenzie’s (2008, p. 117) position on proper names is that they have reference, but not meaning. As such, they occur as the head of a Subact of Reference, a unit used when the speaker attempts to evoke a referent, and they can designate an Individual (x), such as João, a concrete and tangible entity, a Location (l), Brazil, and a Time (t), August. At the Interpersonal Level, the name is marked by the identifiability operator ‘+id’, which reflects its inherent definiteness and, in certain languages, triggers a morphosyntactic marker. As shown in (3), at the Representational Level, the variable corresponding to the proper name lacks a lexical head, which means that the proper name does not have a Lexical Property, i.e., a unit that contains a description of the entity designated. This is the crucial difference between proper names and common nouns. In the case of common nouns, such as homem (‘man’) (4), the Subact of Reference lacks a head, and the individual has a Lexical Property as its head:

- (3)

- (RI: João (RI))

- (xi)

- (4)

- (RI)

- (xi (fi: homem (fi)) (xi))

Although, in the case of proper names, the variable corresponding to the proper names at the Representational Level lacks a head, it can contain contextually given information, such as gender, that triggers the agreement on the adjective in (5).

- (5)

- Portuguese

- Maria

- Maria

- é

- be.prs.3.sg

- bonit-a.

- beautiful-f

- ‘Maria is beautiful.’

As mentioned earlier, in FDG, an absent head implies that it is impossible for a proper name to receive restrictive modification at the Representational Level. This is due to the FDG definition of head and modifier as first and second restrictor. Therefore, when there is an absent head, modification is not possible because the second restrictor would then become the first, that is, the head. For this reason, modifiers of proper names are assumed to occur only at the Interpersonal Level, which is responsible for rhetorical and pragmatic distinctions, and they represent, in this case, the speaker’s assessment of the evoked referent, as indicated in (6).

- (6)

- Portuguese

- O pobre João não tem nenhum lugar para ficar.

- O

- The

- pobre

- poor

- João

- João

- não

- neg

- tem

- have.prs.3sg

- nenhum

- none

- lugar

- place

- para

- to

- ficar.

- stay

- ‘Poor John has nowhere to stay.’

In (6), the speaker does not wish to assign the property of poverty to the referent, as would be the case of O homem pobre não tem onde viver (‘The poor man has nowhere to live’); indeed, what the speaker does is express solidarity and empathy with João for the fact that he is homeless. Thus, the modification, which is typically pragmatic, manifests itself at the layer of the Subact of Reference (R), at the Interpersonal Level, and not at the Representational Level, as occurs in o homem pobre (‘the poor man’) as can be seen in (7) and (8).

- (7)

- O pobre João

- IL: (+id RI: João (RI) : pobre (RI))

- RL: (xi)

- (8)

- homem pobre

- IL: (+id RI)

- RL: (xi: (fi: homem (fi) (xi) :

- (TJ)

- (fj: pobre (fj)) (xi))

The difference in scope and meaning is usually expressed in Portuguese by means of word order, as interpersonal modifiers appear before the head of the Np, whereas representational modifiers occur after the head, as in (7) and (8), respectively.2

Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008, p. 117) also suggest that a proper name can sometimes behave like a common noun (9) and can be used predicatively (10).

- (9)

- There were three Johns at the party (Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2008, p. 117).

- (10)

- My sister Houdini’d her way out of the locked closet (Clark & Clark, 1979, p. 784).

In such cases, the authors argue that the proper names are used as metonyms and should be read as ‘three persons called John’ and ‘act in a way of a person called Houdini’. Because of their special status, the proper names unusually appear at the Representational Level. García Velasco (2009a,b) follows Clark and Clark (1979), who describe the nature of verbal eponyms, like the one in (10), as “contextuals”.

Such an analysis accounts for the fact that verbal eponyms show a number of different senses, have a strong dependence on the context, and presuppose cooperation between the speaker and the addressee for the latter to reach the intended interpretation of the contextuals. García Velasco (2009b, p. 19) points out that for an FDG approach this means that the grammar must interact with the Conceptual Component, because the speaker needs to access relevant information about the eponym that they wish to convey, and then they need to make it compatible with a verbal construction by means of morphological conversion. Note that in FDG, lexemes and frames are separated within the set of primitives of a language. This means that the lexemes are not constrained by predicate frames; rather, the frames are indicators that a lexeme has a certain function within a certain construction. In the case of contextuals, García Velasco (2009b, p. 21) emphasizes that the frame does not trigger the meaning but merely serves as an indicator to help the addressee reach the correct interpretation.

3.2.2. Keizer (2008)

Keizer (2008) proposes an alternative to Hengeveld and Mackenzie’s (2008) approach explaining the category of proper names. She postulates that while proper names do not actually attribute a property at the Representational Level, they do have a set of mental extensions, probably different for each speaker, represented by all entities known as Peter, for example.

The consequence of this position is that, in Keizer’s proposal, the proper name is not defined as an absent head layer at the Representational Level, but as a lexical head without the corresponding property (f) (11), which normally applies to a common noun (12).

- (11)

- Portuguese

- Eu vi Pedro ontem.

- Eu

- 1sg

- vi

- see.pst.1sg

- Pedro

- Pedro

- ontem

- yesterday

- ‘I saw Peter yesterday.’

- IL: (RI)

- RL: (xi: Pedro (xi))

- (12)

- Portuguese

- O homem chegou.

- O

- The

- homem

- man

- chegou

- arrive.pst.3sg

- ‘The man arrived.’

- IL: (RI)

- RL: (xi: (fi: homem (fi)) (xi))

The lack of an f-variable reflects the fact that the proper name does not contain any descriptive content, unlike the common noun in (12), where the Individual homem (‘man’) contains the property of being a man.

Another difference between the two approaches is that Keizer (2008) assumes that proper names can be used ascriptively, as is needed to explain the constructions in (13–14).

- (13)

- I am Peter

- (14)

- The actor Orson Welles

In (13) the speaker does not equate two entities, but uses Peter to instruct the addressee to attach a label to the entity previously referred to by the pronoun I, a situation which Keizer (2008, p. 208) describes as “a special type of ascription”. In (14) the close apposition as a whole consists of one single Subact of Reference containing two non-referential constituents. Accounting for these uses requires an approach that recognizes the use of proper names not only as Subacts of Reference but also as Subacts of Ascription, i.e., the proper name can evoke a referent and also a property, respectively. The fact that the head of the variable is no longer absent, as illustrated in (11), also provides a solution to the problem of restrictive modification, such as (15), in which the adjective suíço (‘Swiss’) restricts the reference:

- (15)

- Portuguese

- em torno da célebre lista dos grandes sonegadores brasileiros que filtrou através do sigilo do HSBC suíço [a operação Lava Jato] fecha-se a omertà (CartaCapital, 860 E18)

- em

- in

- torno

- around

- da

- of.the

- célebre

- famous

- lista

- list

- dos

- of.the

- grande

- great

- sonegadores

- tax_evaders

- brasileiros

- Brazilian.pl

- que

- that

- filtrou

- filter.pst.3sg

- através

- through

- do

- of.the

- sigilo

- secrecy

- do

- of.the

- HSBC

- HSBC

- suíço

- Swiss

- a

- the

- operação

- operation

- Lava

- Lava

- Jato

- Jato

- fecha-se

- close.prs.3sg-refl

- a

- to

- omertà

- silence

- ‘about the famous list of great Brazilian tax evaders that they filtered through the secrecy of the Swiss HSBC, [the Lava Jato operation] keeps it quiet’

Keizer’s view on proper names is helpful to explain the nature of a few phenomena, but it assumes that the variable representing a proper name depends on its mental extension set, which means that such a notion of meaning depends solely on the Conceptual Component. In contrast, I will assume that the lexical meaning is the “outcome of a lexeme with a particular frame” (Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2016, p. 1144), which means that a proper name has no lexical meaning, unless it is coerced into a frame that is not its usual one, as mentioned in the section 3.2.2.

3.2.3. Giomi (2020, 2021)

Recently, Giomi (2020) has dealt differently with interpersonal lexemes, as he proposes that they should be the head of a different type of variable, the Lexical Deed (D). This means that “the insertion of a lexeme in a given position of pragmatic structure amounts to a communicative action that is performed by the speaker in an attempt to influence the addressee’s information state” (Giomi, 2021, p. 214). This results in the representation in (16):

- (16)

- IL: (+id RI: (DI: John (DI)) (RI))

- RL: (xi)

At the Representational Level, the author maintains the idea that proper names do not denote a lexical property and, for this reason, the Individual has an absent head. Giomi (2020) specifically addresses the problem of the modification of absent heads, as in the case of proper names and proforms. Hengeveld and Mackenzie’s (2008) definition of head and modifiers is based on the distinction between first and second restrictors already present in Dik’s (1997) Functional Grammar, which has been carried over to FDG’s approach of modification, in which the head is the first restrictor and the modifier is the second restrictor. Where the head of a variable is absent, as is the case with proper names and pronouns at the Representational Level, no restrictive modification is possible, precisely because the second restrictor would then become the first, that is, the head.

To solve the problem, Giomi (2020) discards the assumption that absent heads cannot be modified. Rather than assuming the distinction between first and second restrictors, Giomi (2020) proposes a distinction between internal and external specifications of a variable. As an external specification, a modifier does not need to attach to an internal specification.

As will be shown in Section 4, Giomi’s proposal applies to non-restrictive modification of proper names at the Representational Level, but still poses a problem for a restrictive modifier, such as (15) above.

4. Proper names in Portuguese

This section presents the analysis of proper names in Portuguese.3 As mentioned previously, there is a great diversity of uses of proper names in Portuguese, which will be covered here: Section 4.1 shows the behaviour of prototypical proper names; Section 4.2 covers the modification of proper names; Section 4.3 deals with proper names used metaphorically; and, finally, Section 4.4 presents the use of proper names in naming constructions.

4.1. Prototypical proper names

The researchers on proper names usually agree that they are, by their very nature, referential and do not have descriptive content. In addition, it is often mentioned that they should not be accompanied by (in)definite articles4 and modifiers, since, given their nature, there would be no need to specify the reference of a lexical item that denotes a unique entity.

Although the lack of modifiers is indeed common in Portuguese, it is possible to find examples that differ in their behaviour. For instance, Portuguese shows great variation regarding the absence (17) or presence (18) of the definite article with a referential proper name.

- (17)

- Portuguese

- Andréia Garcia encara, porém, o desafio com humor, movida pela crença de que os livros melhoram a vida dos leitores. (CartaCapital, 856 R 10–11)

- Andréia

- Andreia

- Garcia

- Garcia

- encara

- face.prs.3sg

- porém

- however

- o

- the

- desafio

- challenge

- com

- with

- humor

- humour

- ‘Andreia Garcia however faces the challenge with humour.’

- (18)

- Portuguese

- Há muito tempo que o Felipão, o Vanderlei Luxemburgo e outros se desinteressaram de trabalhar à beira dos gramados. (CartaCapital, 866 O 72)

- O

- The

- Felipão

- Felipão

- o

- the

- Vanderlei

- Vanderlei

- Luxemburgo

- Luxemburgo

- e

- and

- outros

- others

- se

- refl

- desinteressaram

- disinterest.pst.3pl

- de

- of

- trabalhar

- work.inf

- à_beira_dos

- at_the_side_of.the

- gramados.

- fields

- ‘Felipão, Vanderlei Luxemburgo and others lost interest in working along the touchlines.’

Examples (17) and (18) show proper names being used to evoke referents, which means in FDG that they are instances of Subacts of Reference at the Interpersonal Level. Although both cases do have an identifiability operator +id at the Interpersonal Level, at the Morphosyntactic Level their encoding differs, as (19) shows only the Noun Words (Nw) referring to the names and (20) shows a Noun Phrase (Np) that contains a Grammatical Word (Gw) and the Noun Words (Nw).

- (19)

- IL: (+id RI: Andreia Garcia (RI))

- RL: (xi)

- ML: (Nwi: Andreia (Nwi)) (Nwj: Garcia (Nwj))

- (20)

- (a)

- IL: (+id RI: Felipão (RI))

- RL: (xi)

- ML: (Npi: (Gwi: o (Gwi)) (Nwi: Felipão (Nwi)) (Npi))

- (b)

- IL: (+id RI: Vanderlei Luxemburgo (RI))

- RL: (xi)

- ML: (Npi: (Gwi: o (Gwi)) (Nwi: Vanderlei (Nwi)) (Nwj: Luxemburgo (Nwj)) (Npi))

This behaviour is usually described as a matter of sociolinguistic variation in Brazilian Portuguese, as shown by Callou and Silva (1997). The authors argue that in the South and Southeast of Brazil, the use of a definite article with a proper name is more common than in the North and Northeast. Raposo and Nascimento (2013, p. 1024–1026) argue that, for European Portuguese, the use of the definite article is common with proper names in informal and formal contexts without implying any familiarity or pejorative evaluation, as happens in other Romance languages.

Across these varieties, the presence of the definite article does not seem to be functionally motivated. For this reason, this paper does not consider it relevant for the analysis, unless its presence is functionally required, as when the proper name undergoes modification, a case to be discussed in the next subsection.

4.2. Modified proper names

4.2.1. Interpersonal modifiers

As shown in 3.2.1, proper names allow for interpersonal modification, which captures the speaker’s subjective assessment as in (21), or for non-restrictive specifications as in (22).

- (21)

- Portuguese

- A pobre Maria Luiza se apaixonou com 15 anos e casou com 16. (PORT:B BR novotempo)

- A

- The

- pobre

- poor

- Maria

- Maria

- Luiza

- Luiza

- se

- refl

- apaixonou

- fall_in_love.pst.3sg

- com

- with

- 15

- 15

- anos

- years

- e

- and

- casou

- marry.pst.3sg

- com

- with

- 16.

- 16

- ‘Poor Maria Luiza fell in love at the age of 15 and married at 16.’

- (22)

- Portuguese

- Fagundão, pobre coitado, infelizmente é casado com ninguém mais, ninguém menos que Susana Vieira (PORT:B BR baconfrito)

- Fagundão

- Fagundão

- pobre_coitado

- poor_guy

- infelizmente

- unfortunately

- é

- be.prs.3sg

- casado

- married

- com

- with

- ninguém

- no_one

- mais

- more

- ninguém

- no_one

- menos

- less

- que

- than

- Susana

- Susana

- Vieira

- Vieira

- ‘Fagundão, poor guy, is unfortunately married to none other than Susana Vieira.’

Attitudinal modification at the Interpersonal Level can also be achieved by using a specific type of construction, the binominal de-phrase illustrated in (23).

- (23)

- Portuguese

- não prejudica o pobre do João por um problema nosso (PORT:B BR observatoriodatelevisao)

- Não

- neg

- prejudica

- harm.prs.3sg

- o

- the

- pobre

- poor

- do

- of.the

- João

- João

- por

- for

- um

- a

- problema

- problem

- nosso

- our

- ‘do not harm poor João because of our problem.’

Similarly to adjectival pobre (‘poor’) in (21–22), the noun pobre in (23) does not indicate that the property of financial poverty is being attributed to João, but expresses an assessment by the speaker, who expresses empathy with the referent João. In such binominal constructions, the evaluative nature of the first nominal, which itself points to pragmatic modification, reserves for the second nominal the task of providing the referent of the NP, as discussed in detail in Camacho and Serafim (2021).5

Interpersonal modifiers do not pose any problems for an FDG view of proper names, as their most prominent feature is preserved: the proper name is undoubtedly an interpersonal lexeme, the head of a Subact of Reference, used to refer to a unique entity. The next section, however, deals with different types of modifiers, which challenge the treatment given so far.

4.2.2. Representational modifiers

Although FDG provides a treatment for the above cases and denies the possibility of modification at the Representational Level, it is perfectly acceptable, in Portuguese, to utter a sentence in which the proper name is modified by a lexeme that is representational in nature, as in (24).

- (24)

- Portuguese

- O João pobre não tem onde morar. (O João rico tem.)

- O

- The

- João

- João

- pobre

- poor

- não

- neg

- tem

- have.prs.3sg

- onde

- where

- morar.

- live.inf

- ‘Poor João has nowhere to live.’ (Rich João does.) (=The João who is poor has nowhere to live.)

In such a situation, the modifier expresses a feature of the denoted entity and not an assessment by the speaker. In contrast to (21–23), the example in (24) in fact denotes the financial status of João. Such modifiers are convenient in cases of ambiguity, in which the addressee could misinterpret the referent, as is the case in a situation where there are two men named João, one that is rich, and one that is poor, both known to the participants in the interaction. Thus, to avoid any misunderstanding, the speaker evokes a characteristic that can help the addressee restrict the designation.

In the same type of discourse situation, in which the participants know more bearers of the same name, it is also possible to restrict the reference by means of physical characteristics (25), of place of origin (26), or through an association with another individual (27).

- (25)

- Portuguese

- A

- The

- Maria

- Maria

- loira

- blond.f

- ‘The blond Maria’

- (26)

- Portuguese

- A

- The

- Maria

- Maria

- de

- of

- São

- São

- Paulo

- Paulo

- ‘The Maria from São Paulo’

- (27)

- (a)

- Portuguese

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- do

- of.the

- João

- João

- ‘João’s Mary’ (=The Maria who is somehow related to João)

- (b)

- Portuguese

- (A)

- The

- minha

- my

- Maria

- Maria

- ‘My Maria’ (=The Maria who is somehow related to the speaker)

Finally, a comment needs to be made about the use of (in)definite articles with modified proper names. Sedrins (2017, p. 241) claims that the insertion of an (in)definite article seems no longer optional when the proper name is considered a common noun, i.e., it has a restrictive modifier. In the cases shown in his paper, the name refers to more than one individual bearing the same name. However, when the restrictive modifier provides a distinction between facets or states ascribed to one single individual, the omission of the article is possible:

- (28)

- (a)

- Portuguese

- é fácil compreender que o Brasil com Dilma legalmente reeleita é a solução indispensável, a bem da nossa incipiente democracia. (CartaCapital, 861 E 20–21)

- É

- be.3sg.prs

- fácil

- easy

- compreender

- understand.inf

- que

- that

- o

- the

- Brasil

- Brazil

- com

- with

- Dilma

- Dilma

- legalmente

- legally

- reeleita

- re-elected

- é

- be.3sg.prs

- a

- the

- solução

- solution

- indispensável

- indispensable

- a

- to

- bem

- good

- da

- of.the

- nossa

- our

- incipiente

- incipient

- democracia

- democracy

- ‘It is easy to understand that Brazil with Dilma legally re-elected is the indispensable solution, for the sake of our incipient democracy’.

- (b)

- é fácil compreender que o Brasil com a Dilma legalmente reeleita é a solução indispensável, a bem da nossa incipiente democracia.

- (29)

- (a)

- Portuguese

- Vemos em a vida de São Pedro essa diferença. Primeiro, o Pedro impulsivo e até violento antes do Pentecostes, e depois o Pedro amável e submisso quando ficou cheio do Espírito Santo. (PORT:B BR …rasil-aliriopedrini)

- Primeiro

- first

- o

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- impulsivo

- impulsive.m

- e

- and

- até

- even

- violento

- violent.m

- antes

- before

- do

- of.the

- Pentecostes

- Pentecost

- e

- and

- depois

- after

- o

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- amável

- kind

- e

- and

- submisso

- submissive.m

- quando

- when

- ficou

- stay.pst.3sg

- cheio

- full

- do

- of.the

- Espírito

- Holly

- Santo

- Ghost

- ‘First, the impulsive and even violent Peter before Pentecost, and then the kind and submissive Peter when he was filled with the Holy Ghost.’

- (b)

- Vemos em a vida de São Pedro essa diferença. Primeiro, Pedro impulsivo e até violento antes do Pentecostes, e depois Pedro amável e submisso quando ficou cheio do Espírito Santo.

In (28), Dilma being legally re-elected is a state indispensable for the argument put forward by the journalist, leaving implicit the comparison to Dilma not being re-elected. In (29), however, the two facets of Saint Peter are explicitly compared before and after Pentecost. In both cases the modifiers delimit the reference and the article seems optional (see the contrasting paraphrases in 28–29b). The presence of the article is, therefore, only obligatory in the cases where the coerced proper noun actually refers to more than one individual bearing the same name, and not to all cases of proper names considered common nouns.

The previous cases of modification at the Representational Level distinguish two (or more) possible referents denoted by the same name, a typical example of restrictive modification. Non-restrictive modification is also possible when the speaker simply ascribes a feature to the designated individuals (30a–b), a situation that does not presuppose more than one individual bearing the same name.

- (30)

- (a)

- Portuguese

- Foi um gesto parecido com o olhar glacial que ela endereçou a um sorridente Joaquim Barbosa no enterro de Niemeyer (PORT:B BR ailtonmedeiros)

- Foi

- was

- um

- a

- gesto

- gesture

- parecido

- similar

- com

- with

- o

- the

- olhar

- look

- glacial

- glacial

- que

- that

- ela

- she

- endereçou

- addressed

- a

- to

- um

- a

- sorridente

- smiling

- Joaquim

- Joaquim

- Barbosa

- Barbosa

- no

- in.the

- enterro

- funeral

- de

- of

- Niemeyer

- Niemeyer

- ‘It was a gesture similar to the glacial look she gave a smiling Joaquim Barbosa at Niemeyer’s funeral’.

- (b)

- Portuguese

- o sorridente Mark Foster (teclados, guitarras e vocais); o vibrante Mark Pontius (bateria) e o charmoso Cubbie Fink (baixo) são uns lindos (PORT:B BR mundolivrefm)

- o

- the

- sorridente

- smiling

- Mark Foster

- Mark Foster

- (teclados,

- (keyboards,

- guitarras

- guitars

- e

- and

- vocais)

- vocals

- o

- the

- vibrante

- vibrant

- Mark Pontius

- Mark Pontius

- (bateria)

- drums

- e

- and

- o

- the

- charmoso

- charming

- Cubbie

- Cubbie

- Fink

- Fink

- (baixo)

- bass

- são

- are

- uns

- indef.pl

- lindos

- handsome.pl

- ‘the smiling Mark Foster (keyboards, guitars and vocals); the vibrant Mark Pontius (drums) and the charming Cubbie Fink (bass) are handsome’

The speaker does not contrast two different entities in this case, but merely ascribes a property to an entity. As these are not the speaker’s assessments of the referent, but characteristics attributed to the Individual, these modifiers can only be located at the Representational Level. Van Langendonck (2007, p. 178) points out that, in a similar English construction (a devastated Claes), the proper name fulfils its primary function, referring to a unique entity. The same happens in quantificational constructions, such as (31) and (32):

- (31)

- Portuguese

- A tangerina é cultivada em todo o Brasil (NOWPT:19-06-30 BR G1)

- A

- The

- tangerina

- tangerine

- é

- be.prs.3sg

- cultivada

- cultivated

- em

- in

- todo

- all

- o

- the

- Brasil

- Brazil

- ‘The tangerine is cultivated throughout Brazil’.

- (32)

- Portuguese

- A estiagem deste inverno pôs metade do Brasil no nível mais alto de risco de incêndio. (NOWPT:18-08-13 BR G1)

- A

- The

- estiagem

- drought

- deste

- of.this

- inverno

- winter

- pôs

- put.pst.3sg

- metade

- half

- do

- of.the

- Brasil

- Brazil

- no

- in.the

- nível

- level

- mais

- more

- alto

- high

- de

- of

- risco

- risk

- de

- of

- incêndio

- fire

- ‘This winter’s drought has put half of Brazil at the highest level of fire risk’.

In (31) and (32), the quantificational constructions with todo (‘all’) and metade de (‘half of’) refer to a uniquely identifying entity, as there is no opposition between several Brazils, which means that the proper name is not used as a common noun. This is the opposite situation to (24–29), in which there are several individuals that bear the same name, allowing restrictive modification.

In the case of proper names accompanied by representational modifiers, the whole noun phrase is referential and the name itself is not provided with descriptive content. As we have seen above, assuming Hengeveld and Mackenzie’s (2008) conception of proper names does not provide sufficient means to deal with these cases, as an absent head variable cannot undergo modification. As mentioned earlier, in Keizer’s (2008) proposal, the denotation of the variable headed by the proper name depends only on a mental extension set, which means that it does not depend on the grammar itself. Therefore, we resort to Giomi’s (2020) proposal in order to explain the nature of modified proper names.

In Giomi’s (2020) view, the relation of modification no longer entails a first and second restrictor, but rather an internal and an external specification, which means that the restriction on modifiers of an absent head no longer applies. Giomi (2020) points out that this proposal is appropriate for both restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers. What follows from this definition is the formalization in (33) for um sorridente Joaquim Barbosa (‘a smiling Joaquim Barbosa’):

- (33)

- IL: (RI: Joaquim Barbosa (RI)

- RL: (xi) : (fi: sorridente (fi)) (xi))

In fact, in Portuguese, this solution only applies to non-restrictive modification such as that in (33) in which the modifiers indicate states or properties ascribed to the referent. Restrictive modification, however, remains a problem. A proper name with a restrictive modifier loses its feature of referring to a unique entity, as shown in (34):

- (34)

- Portuguese

- não se trata de uma Kahlan boa e uma má, ou clone. Acontece que ao usar o medalhão Kahlan foi separada em duas partes (PORT:B BR apaixonadosporseries)

- não

- neg

- se

- refl.3sg

- trata

- deal.with

- de

- of

- uma

- a

- Kahlan

- Kahlan

- boa

- good

- e

- and

- uma

- a

- má

- bad

- ou

- or

- clone

- clone

- ‘it’s not about a good Kahlan and a bad Kahlan, or a clone. It turns out that when wearing the medallion Kahlan was separated into two parts’

The proper name here functions as a lexically filled head of an Individual rather than an absent head. See the following example with a common noun from Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008, p. 143):

- (35)

- Mary wants a goodlooking man

- (xi: (fi: man (fi)) (xi): (fj: goodloking (fj)) (xi))

- but I prefer an honest one.

- (xj: (fi) (xj): (fj: honest (fj)) (xj))

Each noun phrase denotes a different entity, (xi, xj), and the property man is anaphorically retrieved by the pronoun one, which is represented by the coindexed variable (fi). In (34), the second Np cannot retrieve a property of Kahlan, notably because such a property does not exist: in fact, what is retrieved is the label “Kahlan”.

This non-uniquely referring use of a proper name is usually analysed in terms of type coercion, in which a proper name is converted into a common noun, as defined in Audring and Booij (2016, p. 621–622). If we apply the FDG notion of coercion according to which a lexeme strongly associated with a frame is forced into a different frame for expressive purposes, than the lexeme in the head of a Subact of Reference would enter the Representational Level as the head of an Individual (x).

- (36)

- A Kahlan má

- (xi: Kahlan (xi) : (fi: má (fi)) (xi))

Such a formalization is similar to the one in Keizer (2008). However, by no means do they entail the same analysis, as no mental extension set is available here. If, on the one hand, this analysis covers the possibility of restrictive modification, on the other, it fails6 to explain the anaphoric reference in (34), in which the modifier is ascribed to a different individual, whose label is identical to the one previously mentioned.

What is common to examples with restrictive modifiers is that the proper name behaves merely as a label. Given its nature, the name could be seen as a case of “reflexive language” (Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2008, p. 275–277) since, to some extent, one uses the language to talk about the language (i.e., to talk about a label). This means that a unit of the Interpersonal Level enters the Representation Level, namely, the layer of the Lexical Deed (corresponding to the interpersonal lexeme) enters the Representational Level as the head of an Individual:

- (37)

- RL: (xi: (DI: Kahlan (DI)) (xi) : (fi: boa (fi)) (xi)) (xj: (DI) (xj) : (fj: má (fj)) (xj))

In this way, a variable can be retrieved and co-indexed (DI) as the head of the Individuals (xi, xj), which explains the non-realization of the head of the second Noun Phrase.

This analysis also accounts for the pluralization of these modified proper names. Consider, for instance, the example in (38):

- (38)

- Portuguese

- nasceram um sem número de Beatrizes, Matildes, algumas Laras, algumas Mafaldas, Marias, Leonores e uma Carolina (PORT:B BR nomesportugueses)

- nasceram

- born.pst.3sg

- um

- a

- sem

- without

- número

- number

- de

- of

- Beatriz-es

- Beatriz-pl

- Matilde-s

- Matilde-pl

- algumas

- some

- Lara-s

- Lara-pl

- algumas

- some

- Matilde-s

- Matilde-pl

- Maria-s

- Maria-pl

- Leonor-es

- Leonor-pl

- e

- and

- uma

- a

- Carolina

- Carolina

- ‘a countless number of Beatrizes, Matildes, some Laras, some Mafaldas, Marias, Leonores and a Carolina were born’

At the Interpersonal Level, a Subact of Reference must be responsible for the evocation of the referent denoted by the Individual (x), which in turn, is further specified by the Lexical Deed (D).

- (39)

- IL: (RI)

- RL: (m xi: (DI: Beatriz (DI)) (xi))

The fact that the Lexical Deed is placed as the head of the Individual guarantees that plural operator (m) scopes the layer of the individual, which is encoded by the plural affix –s at the Morphosyntactic Level. A distinct analysis will be provided in Section 4.4 for proper names within the scope of verbs such as chamar (‘to call’) or nomear (‘to name’).

As seen so far, restrictive and non-restrictive representational modification of proper names should be dealt with differently. On the one hand, when there is non-restrictive modification at the Representational Level, the proper name keeps its primary function and the modifier can be associated with an absent head, as proposed by Giomi (2020). On the other hand, where the modifier is restrictive, the proper name no longer refers to a single entity, and it is analysed as an instance of reflexive language, which for proper names is the insertion of a Lexical Deed as the head of an Individual.

4.3. Proper names used metaphorically

This section deals with metaphorical uses of proper names that fall under the label of “contextuals” (Clark & Clark, 1979). These are expressions that have a number of senses and are strongly dependent on their context of use, so that the role of the context is to guide the addressee to the correct interpretation of the expression. This is because out of context the expression can receive multiple interpretations based on what the addressee knows about the individual who bears the original proper name, and because the meaning of the expression can change from context to context.

Although the contextual link is indeed relevant for the addressee’s correct interpretation, this use still meets FDG’s definition of coercion regarding the speaker’s formulation, as Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008, p. 19) claim that coercion happens when “lexemes that are strongly associated with a particular frame can be forced for expressive purposes into a frame that is usually coupled with lexemes of another meaning class”. Consider the example in (40):

- (40)

- Portuguese

- Independentemente das crises, há sempre liberais dispostos a ser um Leibniz das finanças e falar que este é o melhor mundo possível. (CartaCapital, 865 O 19)

- Independentemente

- regardless

- das

- of.the

- crises

- crises

- há

- there.is

- sempre

- always

- liberais

- liberals

- dispostos

- willing

- a

- to

- ser

- be.inf

- um

- a

- Leibniz

- Leibniz

- das

- of.the

- finanças

- finances

- e

- and

- falar

- say.inf

- que

- that

- este

- this

- é

- is

- o

- the

- melhor

- best

- mundo

- world

- possível

- possible.

- ‘Regardless of crises, there are always liberals willing to be a financial Leibniz and to say that this is the best of all possible worlds.’

The metaphorical process has the effect of allowing for the attribution of the characteristics of the entity bearing the name to the name itself. That is, in (40) a property linked to the individual named Leibniz is ascribed to the liberals in this construction, namely, the property of being an optimist. An analogous case is (41):

- (41)

- Portuguese

- [About politicians that pretend to be something they are not.]

- Algo assim como um Robinson Crusoe que caiu na gandaia. (CartaCapital, 864 E 14)

- Algo

- Something

- assim_como

- like

- um

- a

- Robinson

- Robinson

- Crusoe

- Crusoe

- que

- that

- caiu_na_gandaia.

- was_on_the_razzle

- ‘Something like a Robinson Crusoe that went on the razzle’.

In (41), Robinson Crusoe does not refer to the character in a work of fiction, but to the features of that character which are related to a non-fictional context, i.e, that of Brazilian politics.

In these cases, an indefinite article is normally used, as a morphosyntactic reflex of the operator [-id] at the Interpersonal Level, the presence of which is mandatory in this use. In addition, there is the possibility of modifying the name, as in (40), in which das finanças (‘of finances’) establishes the area to which the set of attributes associated with the name applies, and in (41) in which the restrictive clause que caiu na gandaia (‘that went on the razzle’) specifies a situation in which the property applies. Note that modifiers are not obligatory in this use, see for instance the example in (42) where the proper name appears without modification:

- (42)

- Portuguese

- Com estudo suficiente, qualquer um pode ser um Einstein ou um Newton! (PORT:B BR blogdomrx)

- Com

- With

- estudo

- study

- suficiente

- sufficient

- qualquer

- whatever

- um

- one

- pode

- can

- ser

- be

- um

- a

- Einstein

- Einstein

- ou

- or

- um

- a

- Newton

- Newton

- ‘With enough study, anyone can be an Einstein or a Newton’.

These items can be treated as resulting from coercion, that is, as a typical case of an element that shifts to another subclass, in this case a change from the nominal subclass “proper name” to the nominal subclass “common noun”. The speaker no longer evokes a referent by means of assigning a label to him/her, but evokes a property that is being predicated.7 The representation in (43) illustrates this analysis.

- (43)

- IL: (-id RI: (TI)

- RL: (xi: (fi: Leibniz (fi):

- (RI))

- (fj: finanças (fj)) (fi)) (xi))

The formalization in (43) shows how the proper name, an interpersonal lexical item, is forced into a different frame than its usual one. At the Interpersonal Level, a Subact of Ascription (TI) heads the Subact of Reference (RI), as it is a property that is being predicated. This property, at the Representational Level, is introduced as a property variable (f) with a lexical head, which allows modifiers to take that property within its scope.

Also note that the scope of the modifier das finanças (‘of finances’) is not the Individual (xi). If it were, one would expect a predicative paraphrase such as (44) to be grammatical, which is not the case.

- (44)

- *O Leibniz é das finanças.

- (Lit. The Leibniz is of the finances)

In fact, the modifier das finanças only affects the lexical property (fi), which means that a modifier of this sort can only be used attributively, but not predicatively (Hengeveld & Mackenzie, 2008, p. 254–255). The possibility of such modification reinforces the need for a Property (f), as opposed to the situation of restrictively modified proper names.

Having discussed coercion from proper name to common noun, let us now focus on a second kind of type coercion, that from proper name to verb (45).

- (45)

- Portuguese

- Bolsonaro pretende “bolsonarizar” a Educação e a Cultura durante a campanha. (NOWPT:18-02-24 BR Esmael Morai)

- Bolsonaro

- Bolsonaro

- pretende

- intend.prs.3sg

- bolsonar-izar

- bolsonaro-vs

- a

- the

- Educação

- Education

- e

- and

- a

- the

- Cultura

- Culture

- durante

- during

- a

- the

- campanha

- campaign

- ‘Bolsonaro intends to “bolsonarize” Education and Culture during the campaign.’

The verbal eponym in (45) can in turn be the basis of a nominalization process, as shown by the lexeme bolsonarização (‘bolsonarization’) (46):

- (46)

- Portuguese

- É a bolsonarização da política, ou seja, o emburrecimento da política na falta de um projeto de desenvolvimento concreto. (NOWPT:18-05-13 BR Esmael Morai)

- É

- Is

- a

- the

- bolsonar-iz-ação

- bolsonar-vs-nmlz

- da

- of.the

- política

- politics

- ‘It is the “bolsonarization” of politics, that is the dumbing down of politics in the absence of a concrete development project.’

Both (45) and (46) contain a proper name that needs complements to designate a State-of-Affairs properly. In such cases, a Configurational Property (fc) is introduced at the Representational Level to account for the relation between the predicate and its arguments, which accounts for the fact that proper names are forced into a frame that is not the one generally associated with them.

- (47)

- Ele bolsonarizou o sistema de educação.

- (CI:

- (ei:(fci:

- (TI)

- [(fi: Bolsonaro (fj))

- (RI)

- (xi)A

- (RJ)

- (ej: – sistema de educação – (ej))U] (fci))

- (CI))

- (ei))

- ‘He “bolsonarized” the education system’

- (48)

- A Bolsonarização do sistema de educação

- (+id RI: (TI)

- (ei: (fci: [(fi: Bolsonaro (fj))

- (RI))

- (ej: – sistema de educação – (ej))U] (fci))

- (RJ)

- (ei))

- ‘The “bolsonarization” of the education system’

The originally interpersonal lexeme enters the Representational Level as the predicate of a two-place frame. Considering that the addressee knows who the person bearing the name is and is familiar with his acts, then he/she should be able to determine the correct meaning: someone undermined/destroyed the education. The fact that an action is being predicated justifies the presence of the lexeme as the head of a lexical property (fi) at the Representational Level. Bolsonarizar in (47) and bolsonarização in (48) are in a predication frame (fci) together with the Actor (xi) and the Undergoer o sistema de educação (ek) that represent the arguments of the predicate. Both proper names are, at the Interpersonal Level, instances of Subacts of Ascription (T), as they evoke a property, but they do differ with regard to their outer layer, as in (47) the verbalized proper name is part of a Communicated Content (CI) and in (48) the verbalized and then nominalized proper name is part of a Subact of Reference (RI).

The coercion from proper name to common noun involves a metaphorical reading of the proper name as a set of well-known characteristics of an individual. The proper name then loses its most accepted feature, which is its referential status, and in addition, it can be modified. Note that the Subact of Reference as a whole can and does receive an identifiability operator. The coercion from proper name to verb and further from verb to noun involves yet another non-prototypical feature, the necessity of a predication frame in which the proper name enters as the head of the predicate.

4.4. Proper names in naming constructions

Finally, the use of proper names in naming constructions will be discussed. Lyons (1977, p. 217) distinguishes the referential and vocative uses of a proper name and also points out its use in what he calls ‘appellative utterances’, such as This is John or He is called John Smith. He further specifies that this use is a case of didactic nomination,8 in which the speaker instructs the addressee that a name should be associated with a certain entity. See the examples below for Portuguese:

- (49)

- Portuguese

- O produto também não vem da Apis Mellifera, chamada Abelha-Europeia, espécie invasora, mas de dezenas de variedades nativas sem ferrão que habitam a Floresta Amazônica. (CartaCapital, 863 R 10–11)

- O

- The

- produto

- product

- também

- also

- não

- neg

- vem

- come.prs.3sg

- da

- from.the

- Apis

- Apis

- Mellifera,

- Mellifera

- chamada

- called

- Abelha-Europeia

- Abelha-Europeia

- ‘The product also does not come from Apis Mellifera, the so-called European Bee, an invasive species, but it comes from dozens of native stingless varieties that inhabit the Amazon Forest.’

- (50)

- Portuguese

- Eu tenho onze anos e minha melhor amiga se chama Maria Victoria. (PORT:B BR nomesportugueses)

- Eu

- 1sg

- tenho

- have.prs.1sg

- onze

- eleven

- anos

- years

- e

- and

- minha

- my

- melhor

- best

- amiga

- friend

- se

- refl

- chama

- call.prs.3sg

- Maria

- Maria

- Victoria.

- Victoria

- ‘I am eleven years old and my best friend is called Maria Victoria.’

In (49) and (50), the proper names are not used to refer to an entity. In fact, they are used to assign a label to an entity already referred to previously in the discourse. In (49), first, there is the reference to Apis Mellifera, a species of bee, and then there is a labelling of this entity. The label does not correspond to a Subact of Reference, as it does not evoke a referent; in fact, this type of construction establishes a kind of ascription, in which the speaker instructs the addressee to attach a label to an available entity. This fact is clear in (50), in which the instruction is to attach the label Maria Victoria to the referent minha melhor amiga (‘my best friend’).

These cases constitute what Hengeveld (1992) calls a quotative argument, and as such, a typographical adaptation, such as the use of quotation marks, should reveal the nature of this argument, as shown in (51).

- (51)

- Portuguese

- Ao abandonar o PT à época do chamado “Mensalão”, Bicudo deu crédito a acusações em boa parte mal formuladas e inequivocamente hipócritas, mas seu gesto poderia ter sido ditado por um impulso moral. (CartaCapital, 866 E 12)

- Ao

- When

- abandonar

- leave.inf

- o

- the

- PT

- PT

- à

- at.the

- época

- time

- do

- of.the

- chamado

- so.called

- “Mensalão”

- Mensalão

- Bicudo

- Bicudo

- deu

- give.pst.3sg

- crédito

- credit

- acusações

- accusations

- ‘When he left the PT at the time of the so-called “Mensalão”, Bicudo gave credit to accusations that were mostly poorly formulated and unequivocally hypocritical, but his gesture could have been dictated by a moral impulse’.

Hengeveld (1992, p. 44) states that the verbs involved in this sort of predication “have in fact more in common with speech act verbs used in direct speech reports than with copular verbs. The particular speech act described is one of naming or calling. ‘Peter’ (the name) is the word one utters when calling Peter (the person)”.

Hengeveld’s proposal is also based on evidence of quotative indexes in African languages. Indeed Güldemann (2008) subsequently shows that several of these languages require the use of a quotative index in naming constructions, which has the semantic notions of calling, naming or labelling, as illustrated by (52).

- (52)

- Anywa (Reh, 1996, p. 495 apud Güldemann, 2008, p. 400)

- mɑ̄nɑ̄dʊ́ɔŋ

- big.one

- cʊ̀ɔ́l

- call:ip

- ní

- quot

- ŋìkáaŋɔ́

- Nyikang

- ‘The eldest was called Nyikang’.

Example (46) shows the presence of a predicate cʊ̀ɔ́l (‘call’), a quotative index ní and a proper name ŋìkáaŋɔ́. Güldemann (2008, p. 399) argues that “the structural affinity between RD [Reported Discourse] in the narrow sense and naming/labelling is based on the fact that both exploit the self-reflexive function of language, involving the use/mention distinction. Both involve linguistic signs (the quote or the name) which identify or ‘mention’ entities of the linguistic world instead of referring to phenomena in the object world”.

This type of analysis differs from so-called metalinguistic theories of proper names (Kleiber 1981; Katz, 2011), according to which the meaning of the proper name as ‘X called Y’ or ‘X is a bearer of Y’. In fact, it is only in a few contexts that the proper name is taken to be an instance of reflexive language. As such, following Dik’s Functional Grammar (1989), Hengeveld (1992) classifies the predicate call as belonging to the subclass of speech act verbs. Following the advances provided by Giomi (2021), this sort of predicate actually should embed a Lexical Deed, i.e., a layer that accounts for the interpersonal lexeme itself, instead of a Discourse Act.

- (53)

- Minha melhor amiga se chama Maria Victoria

- RL: (ei: (fi: [(fj: – chamar-se – (fj)) (xi: – minha melhor amiga – (xi)) (DI: Maria

- Vitória (DI))] (fi)) (ei))

- ‘My best friend is called Maria Victoria’

As a case of reflexive language in which the speaker talks about a label (and assigns it to an available referent) at the Representational Level, the Lexical Deed is inserted as an argument of the predicate chamar (‘to call’). Note that this is slightly different from the analysis provided for restrictively modified proper names: while in (37) the Lexical Deed is the head of the Individual (x), which guarantees the possibility of pluralization and modification of the Individual, the names in predicates such as (54) cannot be pluralized or modified:

- (54)

- *minhas melhores amigas se chamam Marias.

- ‘My best friends are called Marias’.

- *minha melhor amiga se chama Maria boa.

- ‘My best friend is called good Mary’.

Given this difference, I propose that “quotative arguments” or “appellative utterances” should really be considered a naming or labelling use alongside the referential and vocative uses of proper names. In this usage, the name assigns a label to an existing referent and the name itself is not a part of a Subact of Reference nor part of an Individual as is the case of restrictively modified proper names.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this paper has been to provide a description of the uses of proper names in Portuguese and, based on the findings, to present an FDG analysis that covers most of their uses. To situate the discussion, I showed that philosophers and linguists agree that proper names are referential expressions in nature, although no consensus is found regarding whether they have sense or not. Philosophers such as Mill (1868) and Kripke (1980) maintain that names have no sense, while Frege (1948), Jespersen (1924), Russell (2010) and Wittgenstein (1953), argue that the sense of proper names is as underlying definite descriptions. Among linguists, Kleiber (1981) and Katz (2001) hold a similar position, according to which the meaning of a proper name is a predicate such as ‘X called Y’ or ‘X is a bearer of Y’. Lyons (1977), however, argues that the most accepted understanding of proper names is that they have reference, but not meaning. It is precisely this definition that is at the basis of the FDG take on proper names: they are the lexical head of a Subact of Reference at the Interpersonal Level, and, at the Representational Level, there is no designation, therefore, there is no lexical head for the Individual (x). Although this definition covers the most typical use of proper names, a range of other uses have not yet received extensive treatment within FDG.

Within the referential use, when it comes to modification, there are three sorts of modifiers in Portuguese: (i) the interpersonal (o pobre João (‘poor John’)); (ii) the representational and non-restrictive (um sorridente Joaquim Barbosa (‘a smiling Joaquim Barbosa’)); and (iii) the representational and restrictive (o João loiro (‘the blond John’)). The first two types of modifiers do not imply coercion, as the proper name keeps its primary function of referring to a uniquely identified entity. To account for non-restrictive modification, I resort to Giomi’s (2020) proposal on the modification of proper names. I do not follow his proposal when dealing with restrictive modifiers, since they are treated here as cases of reflexive language, in which the Lexical Deed (D) enters the Representational Level as the head of an Individual (x).

I have also dealt with metaphorical uses of proper names, which imply coercion from proper name to common noun or from proper name to verb. The name is forced into a different frame than its usual one, and acts as the head of a Lexical Property, which makes it suitable for the predication of a property.

Finally, I have shown, based on Lyons (1977) and Hengeveld (1992), that in addition to the vocative and the referential uses of proper names, a third category should be distinguished: proper names used in naming constructions. In FDG, these are arguments of the predicates like chamar (‘to call’), and are formulated at the Representational Level directly as a Lexical Deed (D).

Notes

- Although proper names are usually treated as inherently definite, Anderson (2003, p. 352) argues that definiteness is an acquired feature that allows proper names to function as arguments. With evidence from Greek, the author points out that because vocative and naming constructions such as “I name the child Basil” lack the article, “names are inherently neither definite nor indefinite” (2004, p. 471). However, I assume the position defended by FDG, in which referential proper names are inherently definite and languages may differ with respect to the morphosyntactic expression of the definite article. [^]

- See Nhoato (2018) for a classification of noun phrase modifiers in Portuguese within the FDG framework. [^]

- The data presented in this section was collected from a sample of noun phrases headed or modified by proper names in Portuguese extracted from 36 texts from 12 editions of the weekly magazine CartaCapital, published in Brazil. In order to refer to each occurrence, the edition number, the initial letter of the type of text (R for reports, E for editorials and O for opinion pieces) and the page(s) on which they were published are inserted in parentheses at the end of the citation of each occurrence. For example, to refer to an occurrence taken from the text A visão moral de mundo (‘The Moral World View’), by Vladimir Safatle, the index “857 O 41” is inserted indicating, therefore, that the source is the issue 857, the text is an opinion piece, and the respective occurrence is located on page 41 of the magazine’s printed edition. I also consulted the Corpus of Portuguese: NOW (Davies, 2018) and Web/Dialects (Davies, 2016) for specific constructions that were not found in the main corpus. [^]

- Although it is generally stated that proper names are not accompanied by definite articles, recent studies have shown that languages differ in how they mark definiteness of proper names. Handschuh (2017) provides an analysis of 34 languages and shows the distribution of definiteness marking of anthroponyms and common nouns. In most languages, nouns are not marked for definiteness (15/34, 44%), but a number of other languages mark common nouns and proper names with identical forms and under identical conditions (11/34, 32%). There are other languages that only have marking on common nouns (6/32, 18%), and still others that present distinct definiteness marks for common nouns and proper names (1/34, 3%) and, finally, languages that mark common nouns and proper names under distinct conditions (1/34, 3%). See also Salaberri (2020) for a discussion of definiteness marking of anthroponyms and several other name subclasses in 50 languages. This shows a great diversity regarding definiteness marking which usually is not taken into consideration when defining the features of proper names. [^]

- Ten Wolde and Keizer (2016) provide a different analysis for the equivalent English construction within the FDG framework. They argue that, in the similar NP, a beast of a child, the first noun is as a representational modifier. [^]

- Two anonymous reviewers, and the colleagues who attended the Functional Discourse Grammar Online Lecture Series (to which I am grateful), rightfully pointed out that this analysis does not cover the anaphoric reference in (34), as this sort of anaphora requires the co-indexation of a variable which is inexistent if the lexeme appears directly as the head of an Individual. [^]

- Although the speaker clearly predicates a property, the meaning of such predication is only available if we assume an interaction with the Contextual Component. The interpretation of this use of proper names relies on a) the identity of the eponym, as the addressee must be familiar with Leibniz; b) the acts by the eponym (he acted as a mathematician, philosopher, contributed to the field of library science, and so on); c) then the speaker must proceed to the identification of the relevant acts by the eponym (as a philosopher, he worked on identity and contradiction, sufficient reason, optimism, etc); d) the type of act referred to (the development of his work on optimism). These are steps provided by Clark & Gerrig (1983, p. 594); however a further step needs to be taken to understand the use of proper names in non-verbal predications. If on the one hand verbal predicates involve the acts by the referent, on the other the non-verbal predicates involve the features associated with the individual. Therefore, one needs to understand that, by developing a work on optimism, Leibniz is an optimist himself. Consequently, the property that accounts for “being Leibniz” actually should be understood by the addressee as “being optimistic”. The main goal of this paper, however, is not to provide a full account on the interactions of the Contextual and Grammatical components. [^]

- The second use that falls under the label of nomination is performative nomination, as in I name this ship the Queen Elizabeth. This use will not be dealt with here. [^]

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Kees Hengeveld, Roberto Gomes Camacho and Erotilde Goreti Pezatti for their valuable comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. I would also like to thank the members of the FDG Community that have provided indispensable feedback at the Sixty International Conference on Functional Discourse Grammar and at the Functional Discourse Grammar Online Lecture Series. The remaining problems are entirely my responsibility.

This study was financed by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant # 2019/13578-7 and partially financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Grant number 88887.373446/2019-00, to which I am also grateful.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Anderson, J. (2003). On the structure of names. Folia Linguistica, 37(3–4), 347–398. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/flin.2003.37.3-4.347

Audring, B., & Booij, G. (2016). Cooperation and coercion. Linguistics, 54(4), 617–637. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2016-0012

Callou, D., & Silva, G. M. (1997). O uso do artigo definido em contextos específicos [The use of definite article in specific contexts]. In D. da Hora (Ed.). Diversidade linguística no Brasil (pp. 11–27). João Pessoa: Idéia.

Camacho, R. G., & Serafim, M. C. S. (2021). Head identification in binominal constructions. Linguistik Online, 109(4), 3–21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.13092/lo.109.8013

Clark, E. V., & Clark, H. H. (1979). When nouns surface as verbs. Language, 55(4), 767–811. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/412745

Clark, H. H., & Gerrig, R. J. (1983). Understanding old words with new meanings. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 22, 591–608. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(83)90364-X

Davies, M. (2016). Corpus do Português: Web/Dialects. Available online: http://www.corpusdoportugues.org/web-dial/

Davies, M. (2018). Corpus do Português: NOW. Available online: http://www.corpusdoportugues.org/web-dial/

Dik, S. C. (1989). The theory of functional grammar. Dordrecht: Foris.

Dik, S. C. (1997). The theory of functional grammar. Part 1: The Structure of the Clause, Kees Hengeveld. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Frege, G. (1948 [1892]). Sense and reference. The Philosophical Review, 57(3), 209–230. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2181485

García Velasco, D. (2009a). Conversion in English and its implications for Functional Discourse Grammar. Lingua, 119(8), 1164–1185. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2007.12.006

García Velasco, D. (2009b). Innovative coinage: Its place in the grammar. In C. S. Butler & J. M. Arista (Eds.), Deconstructing constructions (pp. 3–24). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.107.03inn

Giomi, R. (2020). Headedness and modification in Functional Discourse Grammar. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics, 5(1), 1–32. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1290

Giomi, R. (2021). The place of interpersonal lexemes in linguistic theory, with Special Reference to Functional Discourse Grammar. Corpus Pragmatics, 5(2), 187–222. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-020-00094-w

Güldemann, T. (2008). Quotative indexes in African languages: A synchronic and diachronic survey. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110211450

Handschuh, C. (2017). Nominal category marking on personal names: a typological study of case and definiteness. Folia Linguistica, 51(2), 483–504. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/flin-2017-0017

Hengeveld, K. (1992). Non-verbal predication: Theory. Typology, diachrony. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110883282

Hengeveld, K., & Mackenzie, J. L. (2008). Functional Discourse Grammar: A typologically-based theory of language structure. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199278107.001.0001

Hengeveld, K., & Mackenzie, J. (2016). Reflections on the lexicon in Functional Discourse Grammar. Linguistics, 54(5), 1135–1161. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2016-0025

Jespersen, O. (1924). Philosophy of grammar. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Katz, J. J. (2001). The end of Millianism: Multiple bearers, improper names, and compositional meaning. The Journal of Philosophy, 98(3), 137–166. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/2678379