1. Introduction – The Romance Pluperfect

To begin, the pluperfect situates a past action before another event in the past. Reichenbach (1947) proposed a framework to visualize the prototypical semantics of the pluperfect, which Comrie (1985) defines as an absolute-relative tense. Reichenbach (1947) shows that an Event time (E) in the pluperfect takes place in absolute time before the Speech time (S) and before some Reference time (R), also in the past. Therefore, with the S occurring at the present moment, an event in the pluperfect appears in Figure 1 below:

To reduce ambiguity found in much of the research on the topic of perfect tenses, it is obligatory to clearly distinguish between form and function. Form refers to the structure, and function to the tense semantics. Therefore, I adhere to the following labels. The morphological forms in question are: the compound past (CP), ex. I have eaten; the simple past (SP), ex. I ate; the pluperfect, ex. I had eaten. The tense semantics in question are labelled: perfect (past event time [E] with a reference time [R] concurrent with speech time [S] in the present; E___R,S), past perfective (past event concurrent with reference time; E,R___S; also sometimes called a preterite or punctual and hereafter referred to as perfective), and past perfect (past event before a past reference time; E__R__S [See Figure 1 above]) (Reichenbach, 1947, updated in Comrie, 1985, and Dahl, 1985). Finally, the label aspect will be used to refer to the temporal semantics of the morphological forms in question. Throughout this paper, these terms will only be employed below with the specific meaning given here.

In the history of the Romance languages, the three most common forms appearing with these latter semantics are: i) the synthetic pluperfect -ra forms descended from the Latin pluperfect indicative in -eram (referred to in this paper as the -ra form), ii) the compound pluperfect (CPP) consisting of an auxiliary (usually have or be) in the imperfect tense with a participle, and iii) the past anterior (PA) formed with an auxiliary in the simple past and a participle. These three forms are shown here below in Portuguese.

eu cantara ‘I had sung’, indicative pluperfect -ra form

eu havia/tinha cantado ‘I had sung’, CPP1

eu houve/tive cantado ‘I had sung’, PA2

In classical Latin, the pluperfect active indicative was a synthetic form, composed of the perfect verb stem and the inflectional suffix -eram, etc., endings (e.g. cantāre ‘to sing’, cantāveram ‘I had sung’) (Lindsay, 1894). According to Bennett (1910) the Latin synthetic pluperfect form “denotes an action prior to another past act or explicit [or implicit] point of time…”, conforming to Reichenbach’s (1947) pluperfect structure of event time before reference time before speech time. However, Bennett (1910) also states that the Latin synthetic pluperfect could be used “to denote state resulting from completed past act”, corresponding with a resultative-in-past function (ex. I had a written letter, which contrasts with the resultative I have a written letter).

The Romance descendants of the Latin synthetic pluperfect will be referred to as -ra forms since that syllable is usually maintained (ex. Port. cantara). There was no grammatical compound form during the classical Latin period except with the auxiliary BE to form the passive and deponent (the restricted class of verbs with passive forms but active meanings) pluperfect. However, there was a compound structure that had a resultative (i.e., non-eventive) value. This can be seen in the clear difference between (1a) and (1b) (Adams, 2013, p. 618).

- (1)

- (a)

- Templum

- Temple

- exornatum

- decorate.PTCP

- habebant

- have.IMPERF.3P

- ‘They had [the temple decorated]’ – stative

- (b)

- Templum

- Temple

- exornauerant

- decorate.PRET.3P

- ‘They decorated/have decorated [the temple]’ – eventive

Whether the Classical Latin compound structure with HAVE was on its way to grammaticalizing into a compound Romance form is an unsettled topic among linguists focusing on Latin. Regardless, the structure was undoubtedly still able to be used as a resultative with a stative/possessive reading, also seen in (2).

- (2)

- Ibi

- There

- castellum

- camp

- Caesar

- Caesar

- habuit

- have.AUX.PRET.3S

- constitutum

- set.up.PTCP

- ‘Caesar had his camp set up there’ (Vincent, 1982, p. 84)

Following the general Romance trend towards more analytic structures, a compound tense formed with an auxiliary in a past tense plus the past participle of the lexical verb, and this structure gradually became available as an option to express pluperfect events (ex. Spanish – había cantado ‘he had sung’). The auxiliary could appear in the imperfect tense (CPP) or in the simple past (PA – ex. Spanish – hubo cantado ‘he had sung’) in earlier stages of the western Romance languages. N.B. This latter structure has continued into several of the modern Romance varieties but with syntactic and/or stylistic restrictions on its use.

All Romance languages have moved from a synthetic pluperfect to an analytic “with the exception of Romanian (ex. iubiseram ‘I had loved’) and Galician which have kept the synthetic form as the sole option” (Söhrman, 2013, p. 179). Portuguese also maintains the -ra form in this role, albeit as a more restricted literary construction (Squartini, 1999). Below in Table 1 is shown which of the three relevant constructions currently exist in which varieties of Romance.3

The three Romance verb forms representing a past event in relation to another past event (adapted from Söhrman, 2013, p. 185). The verbs in the simple pluperfect all translate as ‘I had spoken’.

| Language | Compound Pluperfect | Simple (Synthetic) Pluperfect | Past Anterior |

| Portuguese | tinha/havia + ptcp | falara | – |

| Galician | (habia) + ptcp | falara | (houbera/houbese + ptcp) |

| Spanish | había + ptcp | hablara | hube + ptcp |

| Catalan | havia + ptcp | – | haguí + ptcp |

| Occitan | aviéu/ère + ptcp | – | aguère + ptcp |

| French | j’avais/j’ètais + ptcp | – | j’eus/je fus + ptcp |

| Italian | avevo/ero + ptcp | – | ebbi/fui + ptcp |

| Sardinian | aío + ptcp | – | – |

| Romanian | –(am + ptcp = perfect) | vorbiseram |

Although Spanish is listed as one of the varieties with a synthetic pluperfect developed from the Latin -ra forms, its existence and use is more complex than this chart would suggest. The primary semantic value of this form in Spanish is an imperfect subjunctive, although, albeit in a much more restricted fashion than in Galician or Portuguese, the indicative -ra form continues to be found, especially in journalistic, literary, and poetic contexts, and mostly in relative and adverbial clauses (Hermerén, 1992, p. 28). The original pluperfect indicative use of this form was never lost completely (González Ollé, 2012), although it experienced a steep decline in use after the 15th century (Davis, 1934; Wright, 1932) and then a resurgence in 19th century literary Spanish, especially in varieties in close contact with Galician (Hermerén, 1992). In short, the Spanish CPP was generalized as the unmarked pluperfect over the -ra forms during the 15th century, centuries before Portuguese.

A detailed examination of the situation of the Romanian pluperfect falls outside of the scope of this paper, namely the situation of the Portuguese pluperfect within that of western Romance. However, it is important to note here that although standard Romanian does ostensibly have a synthetic pluperfect, it is vastly different from its use in Portuguese in that it is “entirely replaced by the [CP] and is now restricted to the written language” (Söhrman, 2013, p. 187). Additionally, the pluperfect that is found in these contexts has not descended from the Latin -ra forms, but rather from the Latin pluperfect subjunctive (cantavissem > cântasem), which is also the genesis of the -se imperfect subjunctive forms found in Spanish, etc. (Mallinson, 1988).

Regarding the structure of this paper, in the first section, I introduce the pluperfect as a tense, then discuss the pluperfect in Romance, and then give a detailed overview of the Portuguese pluperfect. I discuss how it is currently understood, first by the previous literature, and then by myself, illustrated with tokens I have collected from the Corpus do Português. In section two, I use the tokens gathered to quantitatively show the development of the Portuguese pluperfect from the simple to the compound form over five centuries. Within the compound form, I show the diachronic change in auxiliary selection, tracing the disappearance of the auxiliaries ser and eventually haver due to the generalization of ter. In section three, I discuss in detail the generalization of ter as the compound pluperfect auxiliary, how this altered the patterns of participle–complement agreement, and the conservative effect this had on semantic interpretation. This data then leads to a proposal using markedness theory and a late markedness shift in the forms of the Portuguese pluperfect to explain why the simple form persisted so much longer than in the rest of western European Romance. Unless specifically mentioned otherwise, all Portuguese tokens cited below were found and extracted during the course of my own research.

1.1. Evolution of pluperfect semantics

This subsection describes the semantic evolution of the pluperfect forms. I first proposed and described the model below in Balla-Johnson (2020), building upon previous work on the compound tenses in Romance, especially that of Squartini and Bertinetto (2000).

The three structures with active indicative pluperfect semantics have several different aspectual interpretations available to them. These include: i) resultative-in-past, a stative reading where a resulting state of a prior action is described, ii) perfect-in-past, and iii) perfective-in-past. Examples of each are listed below in tokens (3)–(5). The latter two both represent eventive predicates, but they sometimes can be differentiated by an optional temporal adverb. A reference time adverbial indicates a perfect-in-past reading, while an event time adverbial a perfective-in-past (Squartini, 1999). All three interpretations were available for the -ra forms from their earliest occurrences in Romance.

The question of how exactly these semantic interpretations evolved in the pluperfect has not attracted nearly as much attention as has that of the semantic evolution of the CP and the simple past in Romance. The semantics of the compound structures of the CPP and the PA, however, must have progressed along a cline from resultative-in-past to perfective-in-past during the development of the medieval language. The equivalent structure whose auxiliary appears in the present (ex. Spanish yo he cantado ‘I have sung’) is referred to here as the compound past, rather than the term perfect, here reserved for a specific semantic category. Just as in the development of the CP, the CPP structures with HAVE/HOLD must have originally carried a resultative value and only later extended their aspectual interpretations to include eventive predicates (a process dubbed the perfect-to-perfective shift or aoristic drift described by Bybee et al., 1994; Squartini & Bertinetto, 2000, 2016, and many others). This latter category can be further subdivided into perfects and perfectives.

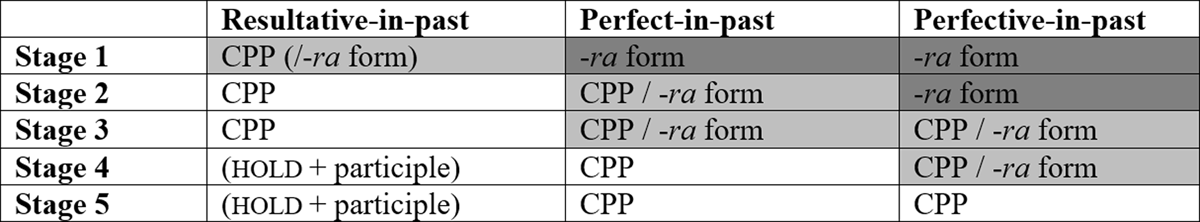

The progression of a Romance variety whose compound pluperfect form has completed this semantic shift (i.e., all except Galician, Asturian, and literary Portuguese) must have passed through the grammaticalization stages shown below in Figure 2.4 This progression was originally proposed in Balla-Johnson (2020), based upon the analogous development in the aoristic drift of the CP.

As Adams (2013) asserts, the CP (and the CPP) structure in Latin was purely stative and not yet able to represent events. Indeed, in discussions of this structure, no attempt to treat the CPP (auxiliary in the imperfect) and the CP (auxiliary in the present) differently is made. In many works, the CP structure in Latin is even explained with examples that appear in the CPP. Thus, at the start of this process of grammaticalization, only the descendants of the Latin synthetic pluperfect—the -ra forms—could be used with eventive predicates (i.e., perfect-in-past/perfective-in-past aspect), and the compound structure was restricted to resultative-in-past interpretations (Stage 1). Then the CPP was extended in a limited context, able to represent an event with perfect-in-past aspect (Stage 2). It then expanded into perfective-in-past contexts (Stage 3). Once the CPP was generalized and established as the default, unmarked form, the -ra forms became more specialized and restricted (Stage 4). The indicative -ra forms were then lost entirely, leaving the CPP as the only option for the eventive uses (Stage 5). Once the CPP becomes the generalized eventive pluperfect, a new structure is needed to represent the resultative-in-past aspect. Varieties such as French and Spanish have turned to the structure of lexical verb meaning ‘to hold/grasp’ plus a participle to communicate this meaning. It is important to note that the chronological duration of each of these stages can differ greatly by variety.

Furthermore, due to the often-unclear division between the perfect-in-past and perfective-in-past (much hazier than the already complicated distinction between the perfect and the perfective) it is not clear that stages 2, 3, and 4 were necessary or present in each language. There must have existed variation of the type seen in stages 2–4, but a progression from stage 1 > 2 > 4 > 5 is just as possible as stage 1 > 3 > 5. Maintaining distinct morphological forms for each of these aspects may not be common cross-linguistically, but it has been shown to exist in 19th century literary Portuguese (Squartini, 1999) and in some Indo-Aryan varieties (Ashwini Deo, personal communication). The relevant fact for this paper is that there was a much more evident distinction between a resultative-in-past (namely, stative) construction and one of either a perfect-in-past or perfective-in-past (namely, eventive) construction.

Three example tokens from the Corpus do Português which represent each aspectual reading appear below in (3) – (5). Semantically, token (3) corresponds with resultative-in-past, token (4) perfect-in-past, and token (5) perfective-in-past. The CPP is used in (3) and (4), and the -ra form in (5).

- (3)

- …soube

- …know.PRET.1S

- como

- how

- el

- the

- Rei

- king

- d’aragom

- of.Aragon

- tijnha

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- armadas

- arm.PTCP.f.p

- quareēta

- forty

- gallees…

- galleys…

- ‘I discovered how the king of Aragon had armed forty galleys…’

- (Crónica de Dom Pedro 15th c.)

- (4)

- …vi

- …see.PRET.1S

- cahir

- fall.INF

- mais

- more

- neve

- snow

- do

- of.that

- que

- which

- nunca

- never

- tinha

- have.AUX.IMPERF.1S

- visto

- see.PTCP

- ‘I saw fall more snow than I had ever seen’

- (Historia do Japam 16th c.)

- (5)

- …e

- …and

- como

- how

- lembrasse

- remember.PAST.SUBJ.3S

- que

- that

- na

- in.the

- última

- last

- tarde

- afternoon

- lhe

- to.him

- assistira

- attend.RA.PLUPERF.3S

- também

- also

- o

- the

- soldado…

- soldier…

- ‘And as you remember that in the last afternoon the soldier also attended to him…’

- (Aventuras de Diófanes 18th c.)

N.B. Each of the three semantic aspects can appear with each of the three formal structures at different points in the history of Portuguese. For brevity I only provide three, rather than nine, examples here.

1.2. The Portuguese pluperfect

This section describes in turn each of the three most common forms which are, or have been used with, one of the above pluperfect aspects in Portuguese, beginning with the oldest, the -ra form, followed by the CPP, and finally the PA.

1.2.1. Portuguese -ra forms

To begin, in Galician and Portuguese the Latin synthetic pluperfect is maintained (also in Asturian-Leonese),5 though phonologically evolved (Wanner, 2014). Throughout the history of Portuguese, the -ra forms are consistently used to communicate a pluperfect meaning. This includes uses consistent with resultative-in-past aspect (as in (3) above), perfect-in-past aspect (6), and perfective-in-past aspect (7).

- (6)

- E

- And

- Galaaz…

- Galaaz…

- tornou

- turn.PRET.3S

- a

- to

- Dalides

- Dalides

- que

- who

- subira

- mount.RA.PLUPERF.3S

- já

- already

- em

- on

- seu

- his

- cavalo

- horse

- ‘And Galaaz… turned to Dalides who had already mounted his horse’

- (A Demanda do Santo Graal 15th c.)

- (7)

- Alfonso…

- Alfonso…

- era

- be.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- ido…

- go.PTCP…

- e

- and

- ao

- at.the

- tempo

- time

- de

- of

- sua

- his

- partida

- departure

- chegara

- arrive.RA.PLUPERF.3S

- Diogo

- Diogo

- ‘Alfonso had left… and Diogo had arrived at the time of his departure’

- (Décadas da Asia 16th c.)

In Portuguese, the -ra pluperfect “is mainly restricted to the written language” (Hutchinson, Amélia & Sousa, 2018), but in modern Galician the -ra form is the only way to express pluperfect indicative in the verbal system (Santamarina, 1974, p. 103). While the synthetic pluperfect is increasingly rare and restricted in Portuguese, the -ra form used to refer to a pluperfect action is not undergoing any attrition in modern Galician. According to Ivarez and Xove (2002), in Galician an action in the past previous to another past action is expressed with the -ra form even when in modern Portuguese or Spanish the CPP would be required.

In medieval Portuguese, there was also, however, a conditional use of the -ra form as a “future in the past” (Brocardo, 2010), seen in (8).

- (8)

- como quer que aquelle ouvera [have-3sgPLUP] de ser ho seu postrimeiro dia, caa o cavallo errou ho porto (ZCPM late 15th cent.?)

- ‘Even though that day would be his last day (i.e., he died later that day) because the horse did not get to the harbour’ (Cited in Brocardo, 2010, p. 120)

Ali (1964) also cites examples of this conditional perfect use of the -ra form until the 17th century, a phenomenon also observed by Silva (1989) in less than 14% of a little over one hundred tokens extracted from a mid-fourteenth century corpus. Becker (2008) finds that the modal use of the Portuguese synthetic pluperfect fell into disuse in the 19th century. Brocardo summarizes how, in contrast with in other medieval Romance languages where the notable change in the pluperfect was the growing use of the compound over the synthetic form, in medieval Portuguese the primary change in the pluperfect was the loss of this modal interpretation of the -ra form (Brocardo, 2010, p. 120). This trend stands in sharp contrast to the situation in Spanish, which has maintained and indeed expanded the modal use of the -ra forms.6

This unique feature of Portuguese and Galician has been identified as a case of contact effects with the neighboring variety of Spanish. Wright (1932) notes that because the synthetic pluperfect is so commonly used in Galician, even almost a century ago the -ra form “crept into” the Spanish of writers from Galicia. These effects from the contact between Galician and Spanish are bidirectional. Following the Spanish model of two forms for the imperfect subjunctive (cantara/cantase), “the Galician pluperfect also tends to replace the past subjunctive cantase (cf. (Latin-American varieties of) Spanish): Se foras/foses, veríalo ‘If you went there, you would see it’)” (Dubert & Galves, 2016, p. 437). This does not seem to be an indigenous development of Galician, but rather due to contact with Spanish. This is discussed more in Anderson (2017) where it is found that analogical pressures are causing the Galician -ra forms to be used as an imperfect subjunctive (based on the Spanish model) and causing the Spanish -ra forms to be used as a pluperfect indicative (based on the Galician model). The form-function asymmetry of the -ra forms is having an analogical effect on both languages. Likewise, it is possible to hear CPP structures in Galician (ex. había vido ‘I had seen’) developed because of analogy with the Spanish CPP (ex. había visto) (Hermerén, 1992, p. 16).

As already mentioned, in modern Portuguese the synthetic pluperfect -ra form has been reserved for elaborate literary usage since the 19th century (Squartini, 1999), while in all other registers the pluperfect is formed as a compound tense with the auxiliary ter > Lat. tenere ‘to hold/possess’ (Harre, 1991), shown in (ii) above. Curiously, there is auxiliary variation between haver and ter in the modern language, but only in the Portuguese CPP, not the CP which in the modern language categorically selects ter (ex. *ele há cantado).

1.2.2. The Portuguese compound pluperfect

The compound pluperfect (auxiliary in the imperfect tense with a past participle) is already documented in texts from the 13th century and has co-existed alongside the -ra forms in Portuguese for centuries. Historically, first the auxiliaries haver and ser (the latter only used with the so-called unaccusatives), and then ter, were used in the CP and in the CPP (Brocardo, 2010). Example (9) shows an unaccusative CPP formed first with ser (9a), then with haver (9b). As in Spanish, auxiliary BE was lost in favor of HAVE.

- (9)

- (a)

- O

- The

- conde

- count

- dõ

- Don

- Enrryque

- Enrryque

- era

- be.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- viindo

- come.PTCP.m.s

- a

- to

- el

- the

- rey

- king

- D’Aragõ

- of.Aragon

- ‘The count don Enrique had come to the king of Aragon’

- (b)

- em

- in

- aquelle

- that

- año

- year

- avya

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- ētrado

- enter.PTCP.m.s

- duas

- two

- vezes

- times

- em

- in

- sua

- his

- terra

- land

- ‘in that year he had entered two times into his land’

- (Crónica Geral de Espanha de 1344)

The variation between haver ‘have’ and ter ‘have/hold’ is shown in example (10). Neither token here shows participle–complement agreement, which was more common with ter during the 16th century.

- (10)

- (a)

- me

- to.me

- deu

- give.PRET.3S

- hûa

- a

- carta

- letter

- que

- that

- lhe

- to.him

- aviã

- have.AUX.IMPERF.1S

- escrito

- write.PTCP.m.s

- ‘He gave me a letter than I had written to him’

- (Enformaçāo das cousas da China 16th c.)

- (b)

- o

- the

- Soldão

- soldier

- somente

- only

- tinha

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- perdido

- lose.PTCP.m.s

- algûas

- some

- batalhas

- battles

- ‘the soldier […] only had lost some battles’

- (Décadas da Asia (Década Terceira) 16th c.)

Regarding the emerging CPP, several scholars have attempted to explain the diachronic reasoning behind the contemporary synonymity between the synthetic pluperfect and the CPP in Portuguese. The most convincing of those, which will be further developed by my research below, maintains that there originally was a difference in interpretation between the synthetic and the CPP, but it was lost (Lopes, 1997, p. 658). The difference was originally between a resultative state and an event, then in later years between a perfect-in-past and a perfective-in-past. Example (11) illustrates the original distinction.

- (11)

- E

- And

- quando

- when

- seu

- his

- irmão

- brother

- el

- the

- rey

- king

- de

- of

- Sevilha,

- Seville,

- que

- who

- tihna

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- cercada

- surround.PTCP.f.s

- a

- the

- cidade

- city

- de

- of

- Sylves,

- Sylves

- ouvyo

- hear.PRET.3S

- dizer

- say.INF

- como

- how

- ele

- he

- tornara

- return.RA.PLUPERF.3S

- ‘And when his brother, the king of Seville, who had surrounded/besieged the city of Sylves, heard talk of how he had returned’

- (Crónica de Portugal, 1419)

The first verb appears in the CPP and with resultative-in-past aspect (i.e., the city was then in a state of having been surrounded) signaled by the participle–complement agreement between cercada and cidade. The second verb is in the -ra form and refers to an event of returning.

The aspectual nature of that difference is described by Campos (2000, 2005). She maintains that the -ra form signified accomplishment of a punctual event (consistent with either perfect-in-past or perfective-in-past aspect) and that the CPP expresses the state resulting from an accomplished event (consistent with a resultative-in-past interpretation).

Continuing along these lines, Brocardo (2010) states, “at least until the 14th century, attestations of [the CPP] are sometimes ambiguous, allowing either for a compound tense reading or for a reading still compatible with the preservation of the etymological meanings of haver/ter, especially when there is overt agreement” (122). The latter reading refers to resultative-in-past. Several ambiguous tokens which could be stative/resultative or eventive appear below. Example (12) shows the CPP with haver and example (13) shows the CPP with ser, a repeat of token (9a) above.

- (12)

- o

- The

- Mareschal

- Marshal

- de

- of

- Noailhes

- Noailhes

- havia

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- tomado

- take.PTCP

- em

- in

- Catalunha

- Catalonia

- a

- the

- cidade

- city

- de

- of

- Girona

- Girona

- ‘The Marshal of Noailhes had taken the city of Girona in Catalonia’

- (Cartas, Brochado 17th c.)

- (13)

- O

- the

- conde

- count

- dõ

- Don

- Enrryque

- Enrique

- era

- be.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- viindo

- come.PTCP

- a

- to

- el

- the

- rey

- king

- d’Aragõ…

- of.Aragon

- ‘The count Don Enrique had come to the king of Aragon…’

- (Crónica Geral de Espanha de 1344 (Ms. P) 14th c.)

A “more advanced grammaticalization” (i.e., more perfect-in-past/perfective-in-past uses) of the CPP are seen from the 15th century onward (Brocardo, 2010). A clearly eventive pluperfect is shown above in example (9b), identified as such by the temporal adverb referring to event time em aquelle año ‘in that year’.

However, (Brocardo, 2010) notes that even in the earliest Portuguese there was apparent free variation between the CPP of unaccusative verbs (which take the auxiliary BE) and the synthetic pluperfect. Indeed Silva (1989, pp. 446–447) considers these constructions with BE + participle of unaccusative verbs as possibly the only case of compound tense to be found in her 14th century corpus. Constructions with haver and ter had not yet grammaticalized passed stage 1 or early stage 2 on the cline at this point.

Since this use of be + participle to form the analytic pluperfect appears to be a completely grammaticalized continuation of the Latin deponent conjugation pattern, the date around which BE as a pluperfect auxiliary began to be replaced by haver and/or ter can be taken as a date before which the haver and/or ter construction must have reached a similar level of grammaticalization. Brocardo (2010, p. 124) says as much when she finds several examples of haver/ter encroaching upon the territory of BE in the 16th century. “The emergence of (first) haver and (afterwards) ter in constructions with this subclass of verbs (that occurred always with esse in earlier language stages) seems to be a clear sign of the full grammaticalization of the construction as a compound verb form” (125). In other words, when an unaccusative verb like vir ‘to come’, which traditionally could only take BE as an auxiliary (ex. era vindo ‘he had come’), began to appear with auxiliary haver and ter (ex. havia/tinha vindo ‘he had come’), the latter two auxiliaries should be considered at an advanced stage of grammaticalization.

It is this evidence in particular which argues against the notion that perhaps the constructions with haver and ter were semantically quite different, despite the similarity of their surface structures. Ter, if it was able to be used with unaccusative verbs, was not restricted to a clear possessive, resultative use, as the equivalent tener + participle structure in modern Spanish is (Harre, 1991). This is not to say it lost the possessive resultative uses—it certainly did not, a fact which will be shown to be crucial below—only that it had grammaticalized to be a functional alternative to auxiliary haver.

After the loss of ser, eventually, the auxiliary ter became more and more used, to the point where it overcame haver as the preferred auxiliary for the CPP. Originally, as Brocardo affirms, the ter CPP often maintained the notion of possession, as shown in example (14).

- (14)

- Pedia

- Ask.for.IMPERF.3S

- instrumentos

- tools

- para

- in.order.to

- romper

- break.INF

- as

- the

- portas

- doos

- que

- which

- tinhāo

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3P

- ganhado

- win.PTCP

- ‘He asked for tools to break the doors which they had won.’

- (Epanaphora politica primeira 17th c.)

However, ter, as haver before it, could also be found without the necessary interpretation of an ongoing state of physical possession, as in the tokens shown in (15).

- (15)

- (a)

- onde

- where

- as

- the

- demais

- other

- províncias

- provinces

- tinham

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3P

- enviado

- send.PTCP.m.s

- deputados

- representatives.m.p

- ‘Where the other provinces had sent representatives’

- (Cartas, Vieira 17th c.)

- (b)

- que

- who

- tinha

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- emprestado

- lend.PTCP

- dinheiro

- money

- ‘Who had lent money’

- (Prosodia 4 17th c.)

Since it is impossible to have in one’s possession something that has been sent (15a) or something lent away (15b), these tokens show the ter CPP used to represent an event rather than a state with possession. Note also the lack of participle–complement agreement in (15a).

A fairly straightforward question remains about the interpretation of the Portuguese CPP. Given that the Portuguese CP (auxiliary in the present with a past participle) has the unique modern property7 of giving a durative or iterative interpretation to the verbal form,8 why does the CPP not trigger the same iterative reading when the only difference between the two is the tense of the auxiliary? For example, in Portuguese eu tenho estudado means neither ‘I have studied’ (as a parallel construction would in Spanish) nor ‘I studied’ (as a parallel construction would in French or Italian), but rather something more akin to ‘I have been studying’ (Squartini & Bertinetto, 2000). Why wouldn’t the CPP eu tinha estudado communicate the meaning of ‘I had been studying’? Schmitt (2001) explains,

In Portuguese, the [CPP] is always created with the auxiliary in the Past imperfective. De Swart [1998] proposed that the Past Imperfective in French had the property of selecting for homogeneous predicates. Assuming that the French imparfait behaves like the Portuguese imperfective, we should expect this tense to select for homogeneous predicates as well and force coercion: either iteration or a continuous reading. However, as we have seen, the [CPP] in Portuguese does not seem to require iteration of the Perfect predicate nor does it allow a continuous reading. There is an important difference between the [CPP] and the [CP]. While the latter is always deictic in that the Reference time is equal or subsumes the speech time, the [CPP] is always dependent on some other event time. Being anaphoric, it takes the value of some other tense element and is not really able to impose selection restrictions. Consequently the coercion operator does not apply, since although we have the imperfective form, we do not have the imperfective semantics (Schmitt, 2001, p. 444).

In other words, the anaphoric nature of the CPP means that it is more restricted in its possible interpretations, whereas the deictic CP is freer and can develop more specific interpretations such as iteration.

1.2.3. Portuguese past anterior

Finally, the past anterior (PA), the compound form with the auxiliary in the simple past and a participle, is frequent in the early texts of the Corpus do Português but is quickly lost over the subsequent centuries. Bechara (2009) states that Portuguese no longer makes use of the PA but that it did exist in Old Portuguese. Several tokens of the PA in Old Portuguese from the corpus appear below in (16) and (17).

Example (16) shows the PA in a temporal adverbial clause, its customary use in the Romance languages where it exists or did exist. It also displays a lack of agreement between the participle (rezado ‘prayed’) and the direct object (esta oraçon ‘this prayer’) at an early stage in the language.

- (16)

- E

- And

- pois

- then

- ouve

- have.AUX.PRET.1S

- rezado

- pray.PTCP.m.s

- esta

- this

- oraçon

- prayer.f.s

- quanto

- how.much

- tempo

- time

- dissemos…

- say.PRET.1P

- ‘And once I had prayed this prayer for the time we said…’

- (Cantigas de Santa Maria 1 13th c.)

Example (17) shows that the PA can appear in independent as well as subordinate clauses. This use presumably did not persist a great deal longer in the language since the PA is unable to appear in this context even in languages where it survived into the present day. Here there is agreement between the participle (tornados ‘returned’) and the subject (os de Troya ‘those from Troy’).

- (17)

- Et

- And

- os

- they

- de

- from

- Troya

- Troy

- forõ

- be.AUX.PRET.3P

- tornados

- return.PTCP.m.p

- a

- to

- ssua

- their

- çidade

- city

- moy

- very

- tristes

- sad

- et

- and

- moy

- very

- agraueados

- aggravated.PTCP.m.p

- ‘And those from Troy had returned to their city very sad and aggravated’

- (Crónica Troyana 1388)

Token (16) of the PA clearly refers to an eventive predicate (‘prayed a prayer’) where token (17) is more ambiguous between a stative/resulative and eventive reading. The subjects could have returned to the city sad (eventive) or have been back in the city sad (stative/resultative). Without knowing the aspectual intention of the author, it is difficult to be certain about the intended interpretation.

However, the token in (18) shows a clear durative use of the PA. There is also agreement between the participle and the object.

- (18)

- Ora

- Now

- vos

- you

- queremos

- want.PRES.1P

- contar

- tell.INF

- quanto

- how.much

- tempo

- time

- o

- the

- muy

- very

- nobre

- noble

- rey

- king

- dom

- Dom

- Fernando

- Fernando

- teve

- have.AUX.PRET.3S

- cercada

- encircle.PTCP.f.s

- Sevilha.

- Seville

- ‘Now we would like to tell you for how much time the very noble Don Fernando had besieged Seville/Seville besieged’

- (Crónica Geral de Espanha de 1344 14th c.)

The only possible interpretation is a resultative-in-past, namely that Don Fernando had Seville under a state of siege for a certain amount of time. Seville was in a state of being under siege due to having been previously surrounded.

In contrast, token (19) exemplifies the PA used for an eventive predicate.

- (19)

- E

- And

- entam

- then

- alçou

- raise.PRET.3S

- a

- the

- espada

- sword

- e

- and

- talhou-lhe

- cut.PRET.3S-to.him

- a

- the

- cabeça.

- head.

- Depois

- After

- que

- that

- esto

- this

- houvo

- have.AUX.PRET.3S

- feito…

- do.PTCP…

- ‘And then he raised the sword and chopped off his head. After he had done this…’

- (A Demanda do Santo Graal (cópia do século XV))

There is no durative interpretation possible here. The act of “performing a head-chopping” is telic and incompatible with anything but an eventive reading.

1.3. Summary of the Portuguese pluperfect

The -ra pluperfect is maintained in modern Galician, and still exists in Portuguese but is restricted to formal literary registers. The Portuguese PA was originally the most frequent compound form, but it was restricted and lost relatively early on. Portuguese has developed a CPP which still exhibits slight auxiliary variation, but generally prefers ter over haver. As in many other Romance varieties, there were conditional/modal interpretations of the -ra form, but in Portuguese these fell into disuse by the 19th century. The Portuguese -ra forms and the CPP were not exactly in complementary distribution, but rather could make use of different aspectual interpretations at different points in the history of the language. Finally, unlike the unique Portuguese CP, there is no iterative interpretation for the CPP.

2. Diachronic evolution of the Portuguese pluperfect

Portuguese is unlike other Romance varieties, like French and Spanish, in that the CPP did not become the generalized perfective-in-past form until very late (within the last two hundred years). There was still a variety of pluperfect forms available in Portuguese long after other Romance varieties had coalesced around one (usually the CPP). Here the goal is to show as clearly as possible the evolution of the pluperfect using quantitative data collected from the Corpus do Português (Davies & Ferreira, 2006).

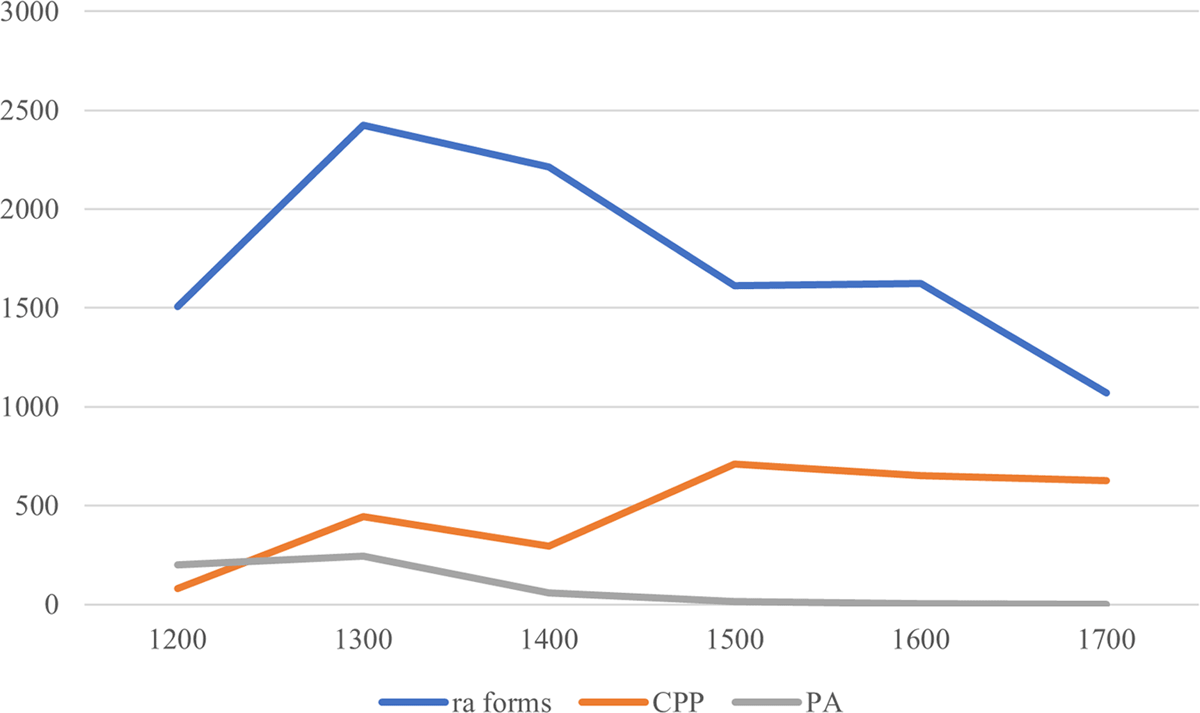

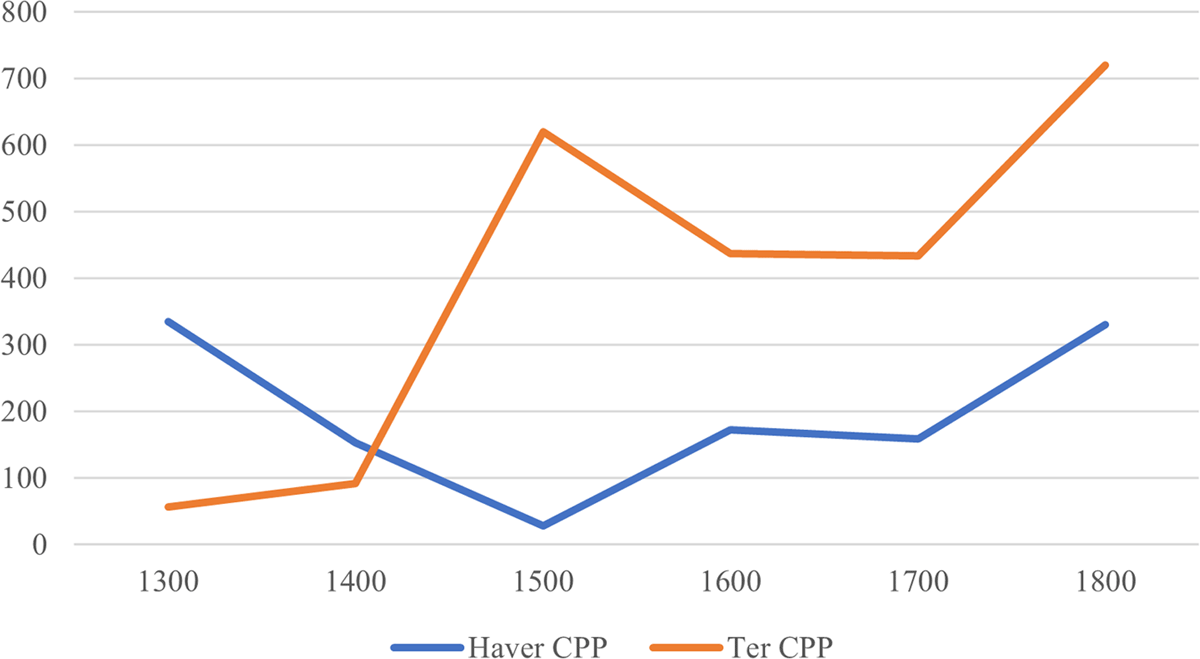

In order to quantitatively display the evolution of the Portuguese pluperfect, several examinations of Portuguese verb forms were conducted using the Corpus do Português. First, a general picture of the diachronic development of the pluperfect verb form is presented for the CPP, the PA, and the indicative (as opposed to modal) -ra pluperfect forms. Next, the auxiliary selection patterns of the CPP and the PA are examined. These results together serve to place 13th and 14th century Portuguese at stage 1 or 2 in the process of pluperfect aspectual development displayed in Figure 3. Even modern Portuguese has not reached stage 5, namely the stage of Old French in c.1200 (Buridant, 2000). During the intervening centuries, Portuguese did progress into stages 3 and 4, with Squartini (1999) clearly establishing 19th c. Portuguese at stage 4.

In order to collect the -ra forms, I created a query in the Corpus do Português which returned every -ra form appearing therein grouped by century (13th–18th). The corpus is able to morphologically identify these forms but has not been built to differentiate between the indicative and various other modal uses. Therefore, within each century I generated a random sample of 50 tokens of verbs appearing in the -ra form. These were each read carefully and classified according to their use. The indicative -ra forms were counted and recorded. The number of indicative forms was divided by the number of tokens in the sample (50). That number was then multiplied by the number of -ra forms per million that occur within that century to find the adjusted number of tokens-per-million for the indicative -ra forms. This value is plotted below for each century. This adjusted tokens-per-million value can then be used to compare frequencies of differing forms within one century and the frequency of a single form across several centuries where the size of the corpus is vastly different.

Collecting the CPP and the PA required a different approach since the corpus does not identify compound verb forms as such, rather it only tags their individual components (ex. instead of havia cantado tagged as a CPP, the havia is a verb in the imperfect and cantado is a past participle). Therefore, the CPP and the PA needed to be consulted individually in the following way. First, a query was created using the collocates function of the corpus which returned all verbs appearing in the imperfect followed by a past participle. Then, a random sample of 100 tokens was generated (a larger sample of 100 was used here to be able to record the differences in auxiliary selection). All active tokens of the CPP (i.e., haver/ser/ter in the imperfect with a past participle) were collected. Passives and any other verbal periphrases were excluded to minimize more complex variables. The same process described for the -ra forms above was used to determine the adjusted number of tokens-per-million based on the ratio found in the sample. This entire process was repeated for the PA, querying forms of the simple past (rather than the imperfect) occurring with the past participle. The results are shown below in Figure 3.

Unlike the rest of western European Romance varieties, the CPP in Portuguese is not the generalized form of the pluperfect indicative even into the 18th century. The -ra forms are greatly preferred even though they show gradual decreases in their use from the 14th century on. The PA initially is more frequent than the CPP in the 13th century, but then almost disappears entirely by the 16th century. The trend lines of the -ra forms and the CPP continue, and they will eventually cross in the following centuries since the CPP is the preferred pluperfect form in modern Portuguese, with the -ra forms restricted to formal written contexts.

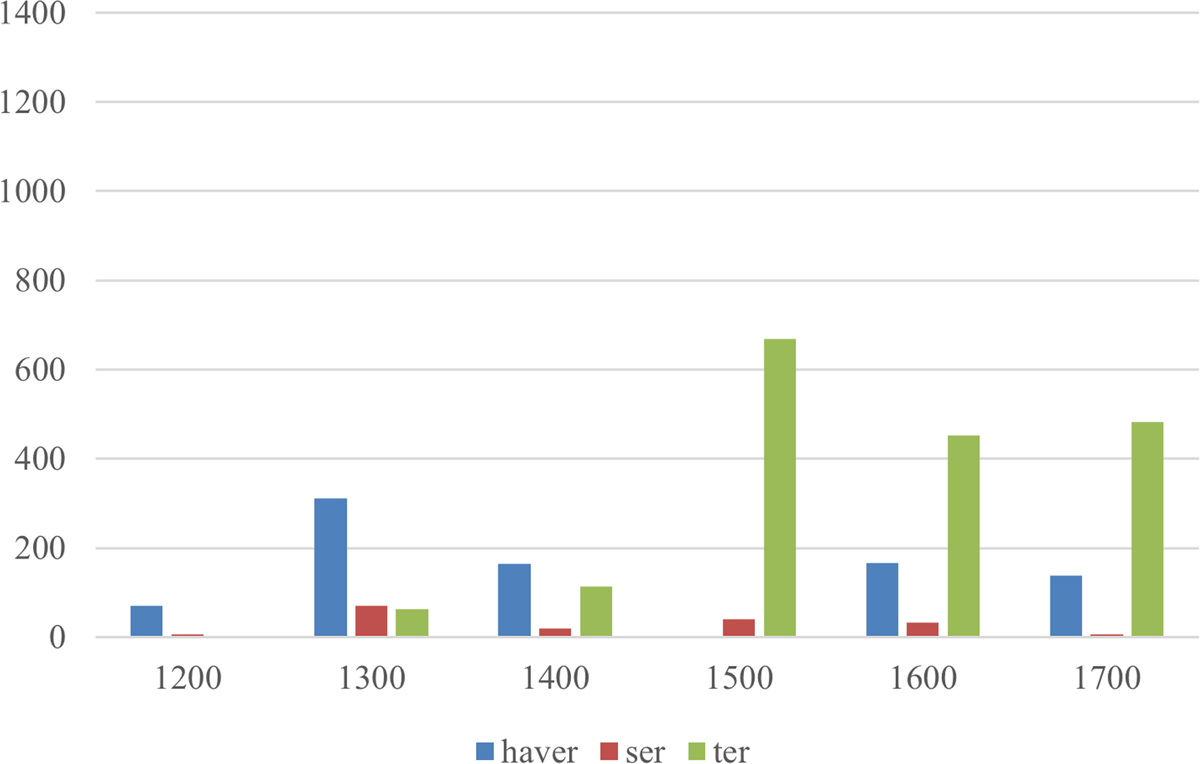

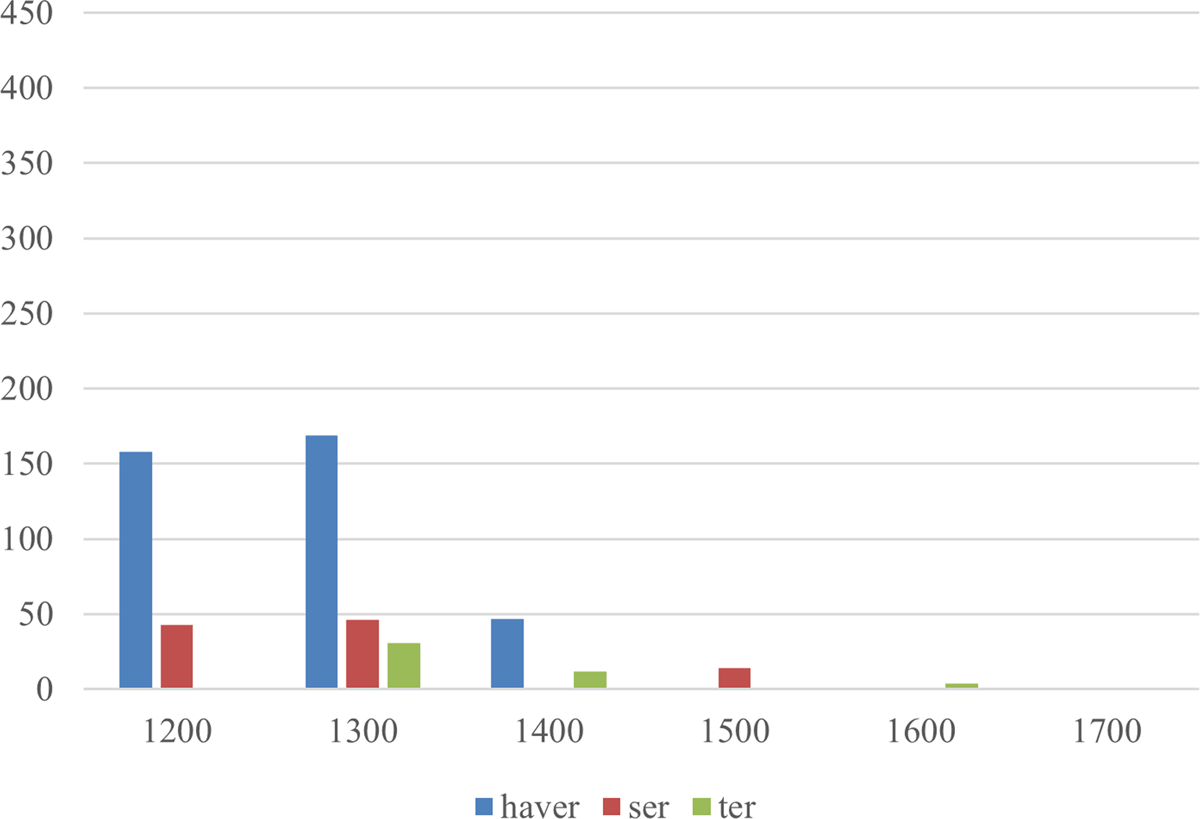

Within the aggregated data showing the frequency of the CPP and the PA, there is important variation in diachronic auxiliary selection. The Figures 4 and 5 below show the distribution of the various auxiliaries used for the CPP and the PA, respectively, in Portuguese.

In the CPP, the auxiliary haver is most frequent until the 16th century, when ter becomes generalized as the preferred CPP auxiliary. Variation between ter and haver nevertheless is shown to persist into the 18th century. In fact, variation between these two auxiliaries has been virtually lost in the CP structure, but it still exists in the modern CPP. Table 2 below shows the results of a series of queries in the modern texts (approximately 1 billion words) in the Corpus do Português. Each auxiliary was searched for in the present and the imperfect followed immediately by a past participle. The tokens were not individually examined, but the general trend is quite clear.

Modern variation between haver and ter in Portuguese CP and CPP.

| Tomar | Chegar | |||||||

| Compound Past | CPP | Compound Past | CPP | |||||

| haver | ter | haver | ter | haver | ter | haver | ter | |

| Token n | 3 | 1428 | 728 | 1190 | 4 | 1491 | 1777 | 3118 |

| Tokens per million words | 0.00 | 1.42 | 0.72 | 1.19 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 1.77 | 3.12 |

| Percent of total N | 0.2% | 98.8% | 38% | 62% | 0.3% | 99.7% | 36% | 64% |

Why auxiliary haver has survived (albeit in a limited fashion) in the CPP is unclear and requires further research. Nevertheless, in the 20th century texts queried here, auxiliary ter is clearly preferred. This generalization of auxiliary ter in the CPP will be appealed to as a crucial factor in the unique evolutionary path taken by the Portuguese CPP.

Finally, the PA almost completely disappears by the 16th century. Haver is the preferred auxiliary for the three centuries where it is found with any frequency, as shown below in Figure 5.

In sum, the Portuguese data show that the -ra forms were not lost and the CPP did not become the generalized perfective-in-past until very recently in the history of the language. Particularly, the -ra forms were maintained far longer as a pluperfect indicative in Portuguese than in the other Romance languages, most notably French or Spanish. The question of why this grammaticalization process lasted so much longer in Portuguese than in the other western European Romance varieties will be addressed next. In the following section, auxiliary ter selection is proposed as the precise cause of the delayed evolution and eventual generalization of the Portuguese CPP.

3. Portuguese auxiliary ter

In this section, the selection of auxiliary ter > Lat. tenere ‘hold’ over haver > Lat. habere ‘have’ as the generalized auxiliary to form the CPP will be analyzed. A hypothesis appealing to this generalization of ter coupled with Markedness Theory is then detailed for why the Portuguese pluperfect differs from the rest of Western European Romance. Briefly put, this change in auxiliary selection in the compound form favored the aspectual reading of resultative-in-past (as opposed to an eventive reading), thus delaying the ultimate semantic shift into the perfective-in-past leading to the loss of the -ra forms. This is not a radical proposal, given the recent work by Amaral and Howe (2009, 2012), who find that auxiliary ter selection in the CP helped maintain a resultative structure, out of which was born the iterative/durative interpretation unique to the Portuguese CP.

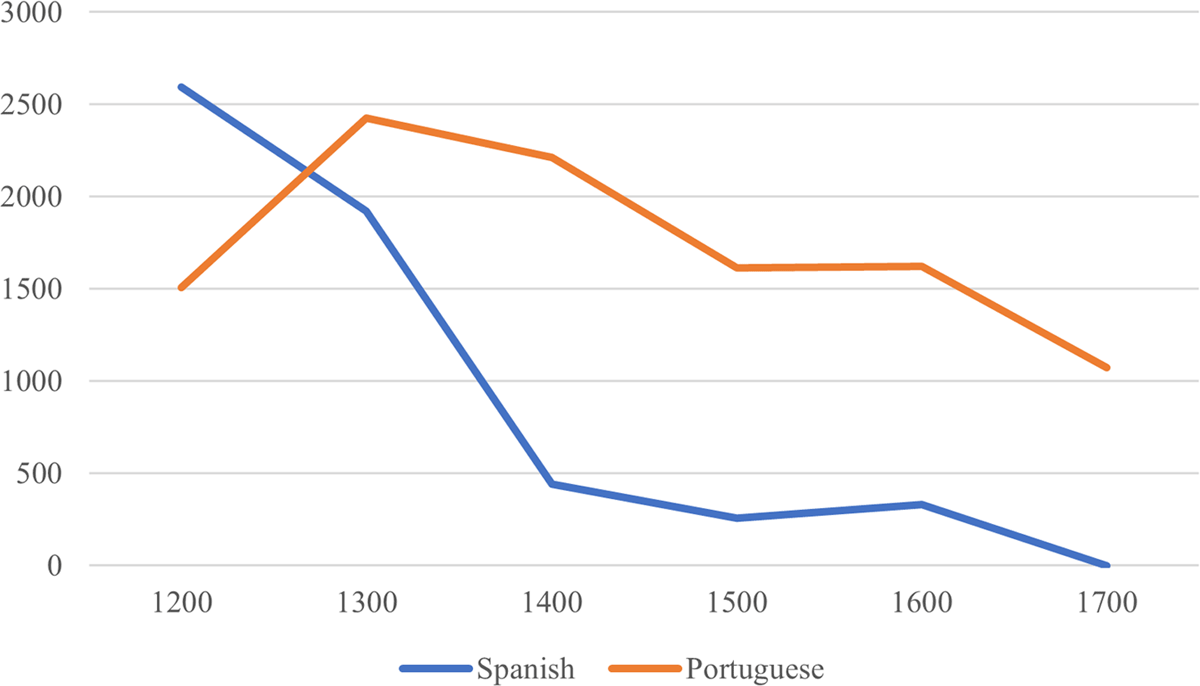

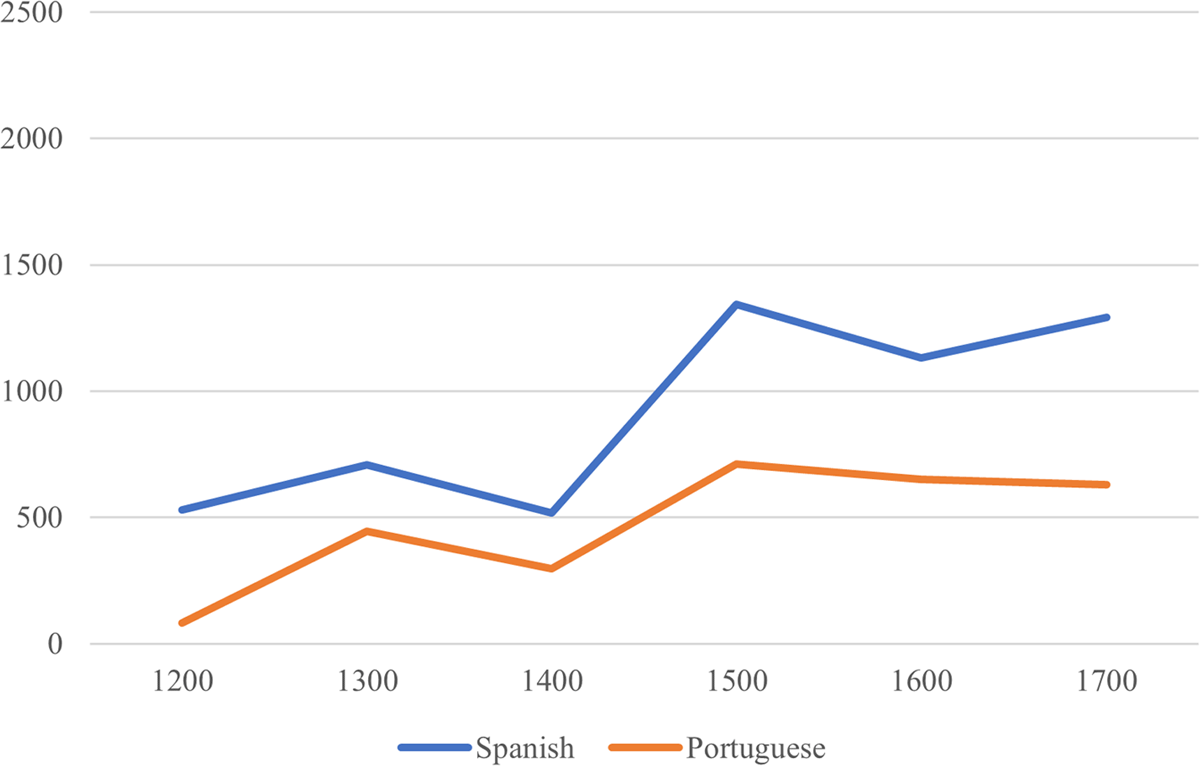

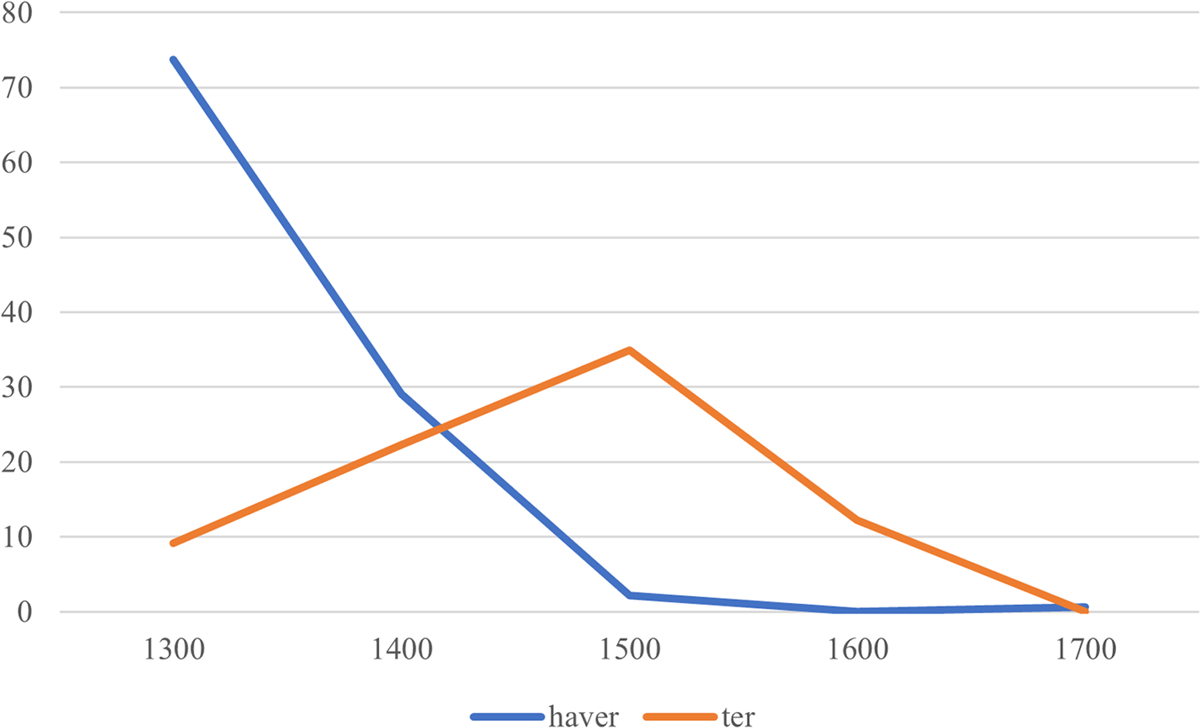

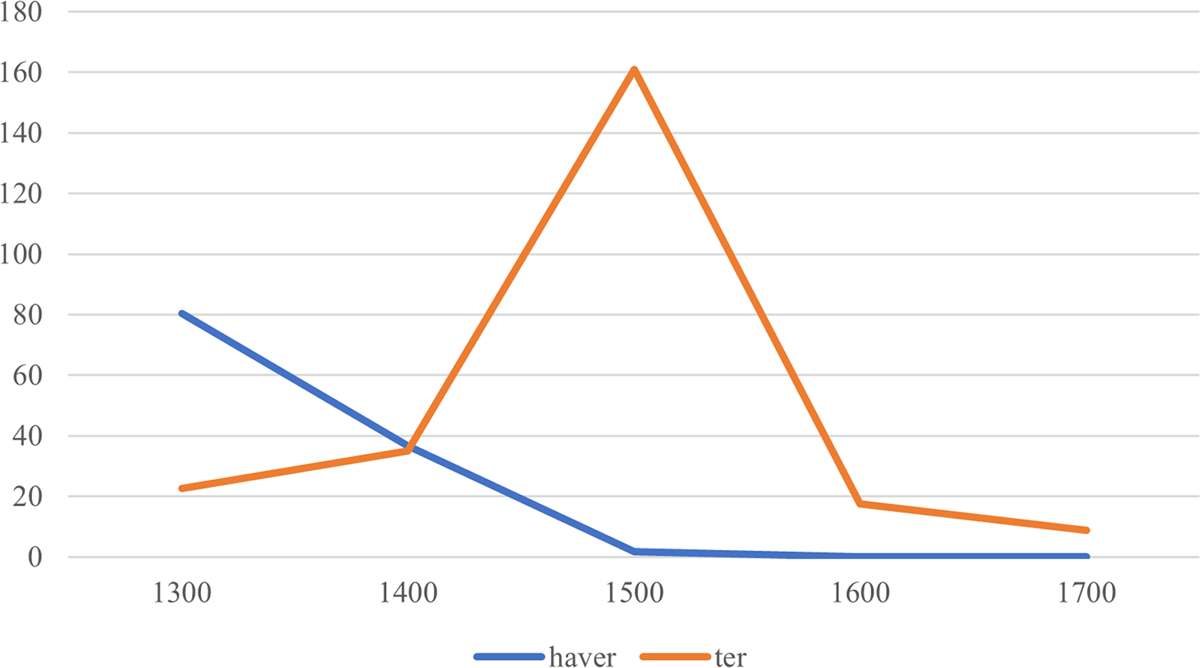

To begin, let us compare the Portuguese pluperfect to that of the closely related variety of Spanish. The figures below show the comparison between the Portuguese data and Spanish data gathered according to the same methodology from the Corpus del Español (Davies, 2002). Each graph shows the diachronic development of one form in the two languages. Figure 6 shows the indicative -ra pluperfects and Figure 7 shows the growth of the CPP on a similar scale.

As is evident, the frequency of the Spanish indicative -ra pluperfect forms decline sharply by the 15th century. In Portuguese, the -ra forms experience a slower decline in frequency and are still found in the modern language, though mostly in elaborate or literary genres. The CPP forms are consistently used more frequently in Spanish than in Portuguese, although both languages show a strong increase from the 15th century on. In sum, throughout the historical period Portuguese has (almost) always used more indicative pluperfect -ra forms than Spanish, and Spanish has used more CPP.

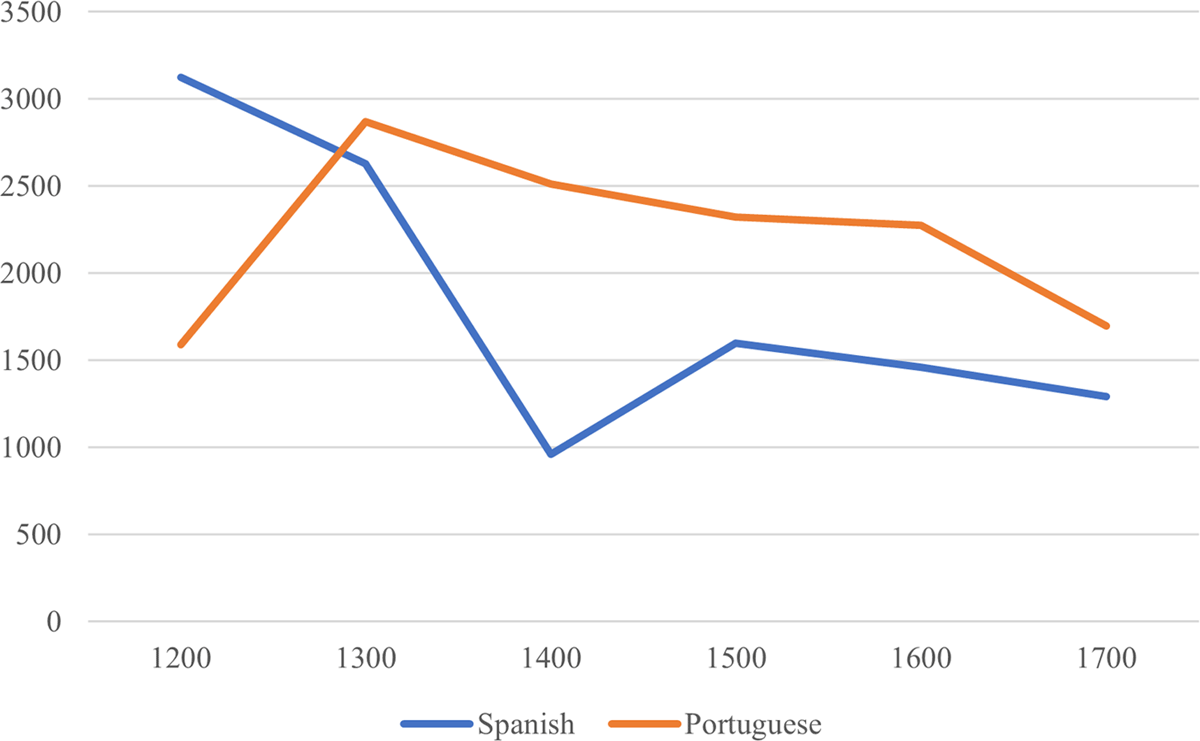

One possible explanation for the divergent behaviors is that the pluperfect in Spanish and Portuguese use different rates of the pluperfect in general. However, Figure 8 below shows the sum of the CPP and the -ra forms for both Portuguese and Spanish across six centuries.

With the exception of the 13th and the 15th centuries, the pluperfect as a general category appears to be used at fairly similar rates in the two languages. There is no vast difference between the overall rates of pluperfect use between the two languages. Because the pluperfect is used in these languages at roughly the same rate their differences are not because of some discrepancy in how often these languages express a past action prior to another.

Despite the diachronically offset similarity of the trends, Portuguese is not simply several centuries behind Spanish in the evolution and generalization of the compound forms. Portuguese differs from Spanish in that auxiliary ter ousted haver as the generalized auxiliary of the compound forms (in contrast to Spanish where haber was preferred over tener). Additionally, the Portuguese CP developed an iterative interpretation, rather than extending its semantic domain into the territory of the simple past (as is happening/has happened in Spanish). These two facts will be shown to be related, but first the generalization of ter will be examined.

3.1. Diachronic expansion of auxiliary ter

Auxiliary ter was generalized as the compound tense auxiliary over haver and ser. Figure 3 above shows this diachronic development (in the CPP) using adjusted token-per-million values calculated from random samples of 100 CPP tokens per century. This data shows the auxiliary ter was clearly the preferred auxiliary by the 16th century.

Although that figure shows the CPP, the CP follows a similar trajectory. Ter is the most frequently preferred auxiliary by the 16th century, although diminished variation with haver is maintained in the CPP into the present (see Table 2).

Since it has been shown that the development of the compound tenses in Portuguese was indeed different than that of Spanish, let us turn to the question of how exactly they differ and what consequences this has had for the development of the aspectual interpretations of the CP and CPP in Portuguese. First, let us examine the chronology of the generalization of auxiliary ter over haver as a past auxiliary.

In order to generate a visual representation of the changing auxiliary preferences in Portuguese, a query was crafted in the Corpus do Português to return tokens of the CPP and the CP using the auxiliaries haver and ter. Ser was not examined. Given that the PA all but disappears and thus does not seem to participate in the change in auxiliary selection in Portuguese, it will not be examined here. Using the corpus query interface, I searched for the auxiliary followed immediately by the participle, with no separation between the two. It would have been possible to add separation using the collocates feature, but this would not return a century’s tokens which could be sampled randomly. Moreover, this was not found to be a problem because the vast majority of the tokens of a compound verb form appear in exactly that order with no intervening material. Excluding other structures may have missed some relevant tokens, but it also minimized the chance of false inclusions where the participle is not associated with the auxiliary (ex. when the participle and auxiliary are not in the same sentence). To illustrate this, Table 3 below shows the number of additional tokens returned when the query is extended up to four lexical slots in each direction for a frequent verb (tomar ‘take’) in the Portuguese CPP. The column labeled +1 represents the tokens which were included in the token pool and then sampled randomly for the investigations to follow.

Portuguese compound pluperfect tomar tokens returned in collocate search by century and number of spaces removed.

| –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 | |

| 1200 | |||||||||

| 1300 | 1 | 26 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1400 | 3 | 3 | haver/ter | 24 | 1 | 5 | 1 | ||

| 1500 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 107 | 6 | 9 | 4 | ||

| 1600 | 2 | 58 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 1700 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

In the 15th and 16th century there are some additional tokens found between two and four spaces to the right of the auxiliary, while the same is true for the 15th century to the left. These are not enough to have a large confounding effect on the overall trends shown by the token counts returned by the corpus in Figure 9. Note that the results of these searches are presented in the exact tokens-per-million, not adjusted tokens-per-million as was generated by the random sample examinations. This method of display was chosen due to the varied number of words included in each of the centuries (i.e., comparing raw token counts between the 2.8 million words of the 15th century and the 4.3 million of the 16th would be unhelpful).

Several observations can be made from the data displayed here. First and most importantly, haver is used at a higher rate than ter in the 15th century, but the opposite is true in the 16th. It was in the 16th century that ter became the generalized auxiliary for the CPP. Continuing, the use of haver with the CPP is shown to rise after almost disappearing in the 16th century. Why there is so little haver CPP in the 16th century is unclear and may be a peculiarity of this specific corpus.

3.2. Auxiliary ter’s impact on the development of the Portuguese compound tenses

Whatever was the exact cause of this generalization of auxiliary ter, the fact that it maintained its full lexical meaning of ‘hold/possess’ into this period (and also into the present) led to an increase in the amount resultative (stative) interpretations of the CP and the CPP, while these related structures were used as perfects (and increasingly perfectives) in neighboring Spanish. This can be imperfectly shown at scale by examining the trends in participle–complement agreement with each auxiliary.

In order to do this, another series of queries were crafted and run in the Corpus do Português. The auxiliary followed by the past participle was queried, for both auxiliaries in the CP and the CPP for five centuries, beginning with the 14th.9 Each of these queries was entered into the chart search option, which returned in one group every token which fit the criteria (ex. haver in the present followed immediately by any past participle, etc.). Both the absolute number of tokens and the tokens-per-million value was recorded. Within the group of tokens, I used the random sample generator to obtain a 50-token sample, which were then extracted and examined thoroughly. This resulted in a total of 987 tokens used for the following analyses (the ter CP in the 14th century only returned 37 tokens. This was the only category with less than 50 tokens collected).

First, since the clearest agreement between participle and complement is able to be recognized when the participle appears in a form other than the masculine singular, Tables 4 and 5 show the breakdown of the participle morphology for each auxiliary in first the CP and then the CPP. Again, note that for the auxiliary ter in the 14th century, there were not 50 tokens to collect. Only 37 were gathered so the percent, not the token number should be used in comparing that century’s data with the others.

Participle number/gender of the Portuguese CP with haver and ter from 14th–18th century.

| Auxiliary | Participle morphology | 1300 | 1400 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| haver | masc sg | 35 | 70 | 40 | 80 | 47 | 94 | 50 | 100 | 49 | 98 |

| other | 15 | 30 | 10 | 20 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| ter | masc sg | 25 | 68 | 38 | 76 | 43 | 86 | 49 | 98 | 50 | 100 |

| other | 12 | 32 | 12 | 24 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

Participle number/gender of the Portuguese CPP with haver and ter from 14th–18th century.

| Auxiliary | Participle morphology | 1300 | 1400 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| haver | masc sg | 35 | 70 | 34 | 68 | 45 | 90 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 |

| other | 15 | 30 | 16 | 32 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ter | masc sg | 28 | 56 | 31 | 62 | 37 | 74 | 48 | 96 | 49 | 98 |

| other | 22 | 44 | 19 | 38 | 13 | 26 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

The results in Table 4 show very similar rates in the participle morphology of the Portuguese CP between the two auxiliaries. The largest discrepancy is eight percentage points (four tokens in the random sample of fifty) between the non-masculine singular participles in the 16th century. Ter is shown to appear slightly more with a masculine plural or feminine participle, which is more likely to be resultative as signaled by the agreement.

The differences between the participle morphology of the auxiliaries are slightly more pronounced in the CPP. The ter CPP in the 14th century appears with non-masculine singular participles at a higher rate than either the haver CPP or the ter CP. There is also a larger difference in the 16th century CPP than in the CP. In Table 5, ter is recorded to appear with non-masculine singular participles 16% more (8/50 tokens) than haver. This is at the time when the overall rates of the ter CPP is about 16 times higher than the haver CPP. Thereafter, the haver CPP is only found with a masculine singular participle, whereas ter shows uses with other participle numbers and genders, albeit rarely.

However, while the morphology of the participle can be used as a proxy for agreement, there is not an exact correspondence between the two. More specifically, not all participles which appear in the masculine singular do not agree with their complement – many do agree. Therefore, the question is posed: Within the contexts of the collected tokens where there was an explicit NP or pronoun with which the participle could agree in number and gender, how often was agreement found?

Using the same data, overt participle and complement agreement was examined. Shown below are the numbers of tokens, divided by the morphology of the participle and the auxiliary, which show overt agreement (as in example (20)) or overt non-agreement (21).

- (20)

- e

- and

- sobre

- on

- todolos

- all.the

- outros

- other

- castelos

- castles

- da

- of

- Estremadura

- Extremadura

- que

- that

- ainda

- still

- não

- not

- tinha

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- tomados,

- take.PTCP.m.p

- ‘And about all the other castles in in Extremadura which he had not yet taken,’

- (Crónica de Portugal 1419)

- (21)

- o

- The

- Soldão

- soldier

- tinha

- have.AUX.IMPERF.3S

- recebido

- receive.PTCP.m.s

- cartas

- letters.f.p

- de

- of

- grandes

- large

- ofertas,

- offers,

- ‘The soldier had received letters of large offers,’

- (Décadas da Asia 16th c.)

Tokens which were classified as ambiguous were excluded since it could not be clearly established if there was participle–complement agreement or not, e.g. token (22).

- (22)

- E

- And

- pois

- then

- tenho

- have.AUX.PRES.1S

- dito

- say.PTCP.m.s

- ho

- that

- que

- which

- pude

- be.able.PRET.1S

- alcançar

- obtain.INF

- dos

- of.the

- casos

- cases

- ‘And then I have said that I could obtain of the cases…’

- (Crónica do Príncipe Dom João 16th c.)

Table 6 shows the results for the CP, when the auxiliary appears in the present, and Table 7 does the same for the CPP, with the auxiliary in the imperfect. The tokens were recorded from random samples of 50 per tense, per auxiliary, per century. Due to the exclusion of the ambiguous tokens which showed neither overt agreement nor overt non-agreement, there is not a consistent number of tokens shown in each century.

Diachronic participle agreement of the Portuguese CP with haver and ter from 14th–18th century.

| Auxiliary | Participle morphology | 1300 | 1400 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | |||||

| Agreement | |||||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| haver | masc sg | 14 | 1 | 14 | 5 | 11 | 17 | 22 | 14 | 11 | 19 |

| fem sg | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||||

| masc pl | 3 | 2 | |||||||||

| fem pl | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| ter | masc sg | 19 | 14 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 13 | 23 | |

| fem sg | 6 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| masc pl | 4 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||

| fem pl | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |||||||

Diachronic participle agreement of the Portuguese CPP with haver and ter from 14th–18th century.

| Auxiliary | Participle morphology | 1300 | 1400 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | |||||

| Agreement | |||||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| haver | masc sg | 14 | 2 | 14 | 7 | 15 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 20 |

| fem sg | 9 | 8 | 2 | ||||||||

| masc pl | 2 | 3 | |||||||||

| fem pl | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| ter | masc sg | 12 | 17 | 1 | 19 | 9 | 17 | 18 | 11 | 22 | |

| fem sg | 11 | 8 | 6 | 1 | |||||||

| masc pl | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |||||||

| fem pl | 4 | 8 | 3 | 1 | |||||||

These results show clearer trends. In general, overt non-agreement between the participle and an explicit complement began a century earlier with haver than with ter (14th and 15th c., respectively), and overt agreement between the participle and the complement persisted for about a century later in compound forms with ter rather than haver. This is demonstrated in Table 8 above where, in the 16th century, there were only three cases of agreement found in the CPP with haver (outside of the masculine singular), compared to 13 in the ter CPP. Next, cases of clear non-agreement do not clearly outnumber the cases of agreement until the 18th century. The actual cases of non-agreement are doubtlessly higher because it is impossible to establish with certainty when the number and gender of masculine singular participles cease to be determined by an overt masculine singular complement. For example, in (21) one cannot be sure if the participle simply appears in the masculine singular as the default form, or if it is controlled by the masculine singular relative pronoun ho que.

Overall distribution of construction types from the Tycho Brahe Parsed Corpus of Historical Portuguese (Amaral & Howe, 2009, p. 397).

| Construction type | 16th century | 18th century |

| Eventive | 24.1% (N = 68) | 74.8% (N = 410) |

| Ambiguous | 61.7% (N = 174) | 19.9% (N = 104) |

| Resultative/Stative | 16.3% (N = 46) | 1.7% (N = 9) |

| Total | 288 | 523 |

Finally, it is important to remember that these are artificially identically sized samples. Fifty tokens were collected for each auxiliary for each century for the sake of comparison. However, the raw results show: (i) the CP is much more frequent than the CPP, and (ii) auxiliary ter is much more frequent than haver in both the CP and the CPP after the year 1500. The trends seen in the tables, like for there to be more agreement (and in particular more non-masculine singular agreement) in ter than haver, become exacerbated when taking the overall frequencies of these auxiliaries into account (shown for the CPP in Figure 9). For example, in the 16th century, 13 out of the 50 possible CPP ter tokens show participle–complement agreement, while only 3 of the 50 haver tokens do. This is already a large difference in the samples (20%), but when applied to the actual number of occurrences per-million it becomes even clearer. The 6% of haver CPP tokens which show participle–complement agreement in the non-masculine singular equates to 1.69 tokens-per-million (.06 × 28.15 total haver CPP tokens-per-million), while the 26% agreement with the ter CPP translates into 161.05 tokens-per-million (.26 × 619.41 total ter CPP tokens-per-million). This 20% difference in the sampled tokens represents the ter CPP actually appearing with non-masculine singular participle–complement agreement almost one hundred times as frequently as the same agreement in the haver CPP. The values presented in Tables 6 and 7 are shown converted into the estimated tokens-per-million according to the method explained above, below in Figures 10 and 11. Due to the difficulty of knowing whether the cases of a masculine singular participle appearing with a masculine singular complement are true cases of agreement (described above), these tokens have been excluded. It bears repeating that the CP (Figure 10), especially in the later centuries is much more frequent than the CPP (Figure 11).

These two figures show that as haver declines in frequency, it also declines in showing overt agreement between the participle and complement. In contrast, ter shows an increase in overall tokens showing this overt agreement between the 14th and 16th centuries. However, this agreement declines sharply and is much less frequent in the 17th century, and all but disappeared in the 18th. Therefore, as the compound forms with ter increase, so does the number of CPP tokens showing agreement. However, even though ter continues its rise in frequency from the 16th century on (shown in Figure 9), participle–complement agreement is quickly lost.

The logical question arises, is participle–complement agreement a reliable indication of a state of lesser grammaticalization? This is a tricky issue since there are varieties (such as French and standard Italian) where the CP and the CPP are clearly fully grammaticalized and yet there are still environments where participle–complement agreement is present. Therefore, recently an idea has been proposed that it is not the presence or lack of agreement (a synchronic notion) which signals advanced grammaticalization, but rather the loss of agreement (a diachronic notion) which can show progression towards a more grammaticalized state (Smith, 2022). In Portuguese, there is a loss of participle–complement agreement with auxiliary haver, but a retention of it for at least another century in constructions with ter. This retention of agreement, breaking the trend seen with haver and extant in the neighboring variety of Spanish, I propose can safely be taken as a signal of lesser grammaticalization.

Therefore, if one can accept that the participle–complement agreement is a proxy (albeit an imperfect one) for stative/resultative semantics of the compound forms, then the data presented above show clearly the generalization of the ter auxiliary did lead to a resultative interpretation of the CP and CPP being maintained longer (into the 17th century) than in other languages. This fact has affected the development of both the CP and the CPP in Portuguese, the former being the more extreme case. These will be examined in turn.

First of all, the development of the CPP in Portuguese was thoroughly treated in Sections 1 and 2. The Portuguese -ra forms persisted as a perfect-in-past longer than in Spanish and French. Then, after being restricted to the perfective-in-past, the -ra forms existed there in variation with the CPP. The restriction happened later in Portuguese than in Spanish. In Spanish, the CPP was expanding as the -ra forms were being used more and more frequently as a conditional or imperfect subjunctive. These two processes exerted both a push and pull effect which put pressure upon the aspectual system of the pluperfect to reorganize. Portuguese did not experience either of these pressures, at least at first. The -ra form did not overwhelmingly become a conditional/subjunctive, and the CPP was being pulled even further away from perfective-in-past uses due to the resultative interpretations associated with the new generalized auxiliary ter. Therefore, whereas languages like Spanish were experiencing two related pressures causing the CPP to become the sole eventive pluperfect, Portuguese lacked one of these (the default interpretation of -ra becoming a conditional/subjunctive) and was experiencing the exact opposite of the other (CPP used more with resultative-in-past meaning). Therefore, the CPP was not semantically extended all the way into the perfective-in-past category until much later than in Spanish and in French. This was, at least in part, due to the generalization of ter which reinforced a resultative reading in the 16th century. Finally, it was only recently that the use of the -ra forms as a pluperfect indicative has been restricted to formal written registers, leaving the CPP as the only unmarked form of the pluperfect indicative.

Second, the CP of Portuguese has developed in quite a unique way within Romance. Amaral and Howe (2009) offer the most thorough and convincing explanation for this innovation.

We claim that the resultative construction is the historical precursor of the [CP] in Portuguese. The emergence of the iterative interpretation of the [CP] requires that the construction ter + Past Participle entails the prior occurrence of the event denoted by the verb, as the [CP] in synchrony denotes event iteration over a time interval. As the prior occurrence of the event denoted by the verb becomes part of the encoded meaning of the form, we expect to see an expansion in the aspectual verb classes that may occur in the construction: the construction is no longer restricted to telic verbs, as was the case in the purely stative resultative construction. We argue that the aspectual shift from the entailment of existence of a single prior event to the entailment of existence of multiple prior events was induced by contexts in which the interpretation of the VP was compatible with both a single and multiple event interpretation (Amaral & Howe, 2009, p. 395, emphasis original).

In summary, according to Amaral and Howe (2009, 2012), this development of the iterative CP arose directly out of the resultative (not perfect) interpretation of the Portuguese CP construction. Therefore, the triumph of ter as the auxiliary of the CP and pluperfect yielded a higher proportion of resultative interpretations for the CP than in other languages (like Spanish). This persistence and reinforcement of the resultative interpretation provided the opportunity for a reanalysis into the modern iterative/durative perfect to take place. The generalization of ter and the development of the iterative CP are thus directly connected. The first change created conditions which allowed for the second to take place.

In order to support their proposal, Amaral and Howe (2009) examine participle agreement in particular as evidence of resultative constructions. Their results for agreement are reproduced below in Table 8. The construction type is classified as “eventive” if there was overt non-agreement between the participle and the complement, ‘resultative/stative’ if there overt agreement between the participle and the complement, and “ambiguous”.10 The final category contains tokens which have no overt complement or whose participle and complement both appear in the masculine singular (in which case it is unclear whether the participle is in its default form or if it is actually showing agreement with the complement).

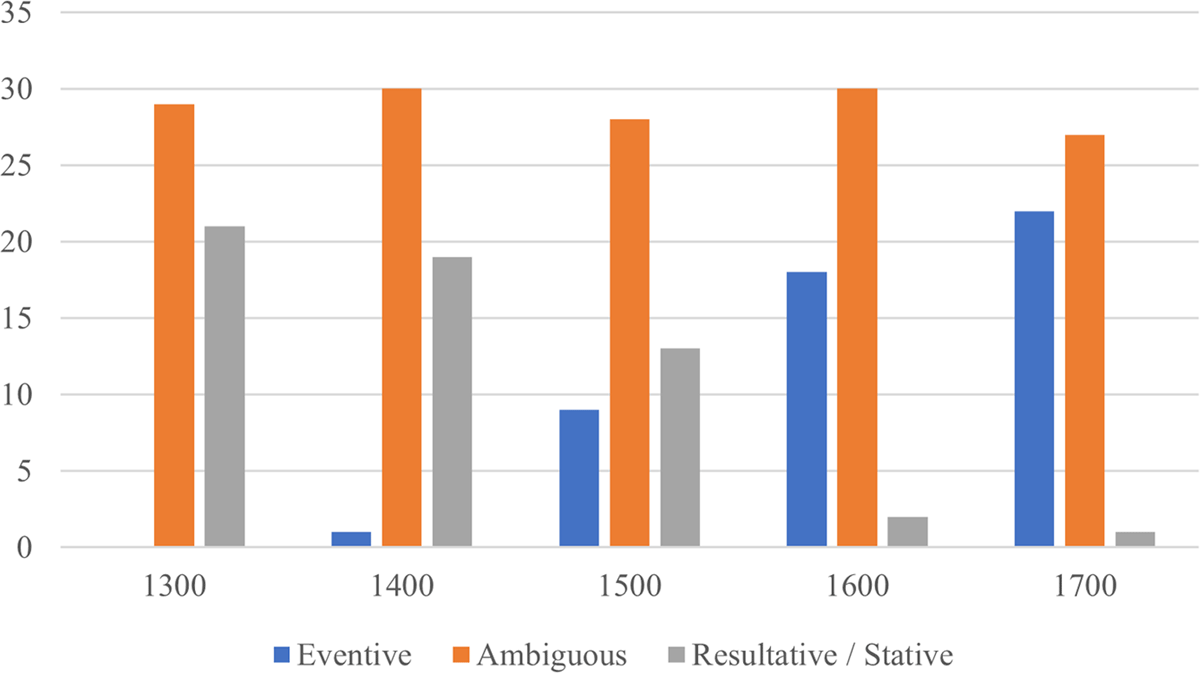

These results show a large increase in the eventive interpretations of the CP structure, based on overt non-agreement between the participle and the complement. Using the same criteria, I consulted my random samples of imperfect ter + participle structure from the Corpus do Português in the same way. My own results, shown here in Table 9 and Figure 12 display the same general pattern for the CPP that Amaral and Howe found for the CP.

Portuguese ter CPP tokens by construction type from 14th–18th century.

| Construction Type | 1300 | 1400 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | |||||

| Eventive | 0 | 0% | 1 | 2% | 9 | 18% | 18 | 36% | 22 | 44% |

| Ambiguous | 29 | 58% | 30 | 60% | 28 | 56% | 30 | 60% | 27 | 54% |

| Resultative/stative | 21 | 42% | 19 | 38% | 13 | 26% | 2 | 4% | 1 | 2% |

Just as in Amaral and Howe (2009), the resultative/stative use decreases over time as the eventive uses increase. The 17th century is when the eventive use of the ter CPP becomes more frequent than the stative11 use. While logical, the documentation of this finding is an important piece in the picture of the Portuguese pluperfect.

This section has shown that the increase in frequency and generalization of ter as a compound form auxiliary led to a greater number of resultative interpretations, recognized by participle–complement agreement, of the CP and CPP than with haver. Quantitative evidence was provided, documenting a greater tendency for this participle–complement agreement in the CPP with ter than with haver until the 17th century. This larger proportion of resultatives was shown to affect the CP and the CPP in different ways. First, the CPP was delayed in its progression to become a generalized perfective-in-past. Second, the CP developed from the resultative interpretation into the modern iterative Portuguese CP (Amaral & Howe, 2009).

3.3. Markedness and Partial Blocking

It has been shown that the CPP with ter generalized over haver by the 16th century. The question remains: why would this generalization of ter lead to a strong persistence of the pluperfect indicative -ra forms? Namely, the haber CPP generalized in Spanish and the indicative -ra forms were mostly lost by the 15th/16th century. Why did this not happen contemporaneously in Portuguese? These different processes in Spanish and Portuguese will be addressed here by appealing to Markedness Theory.

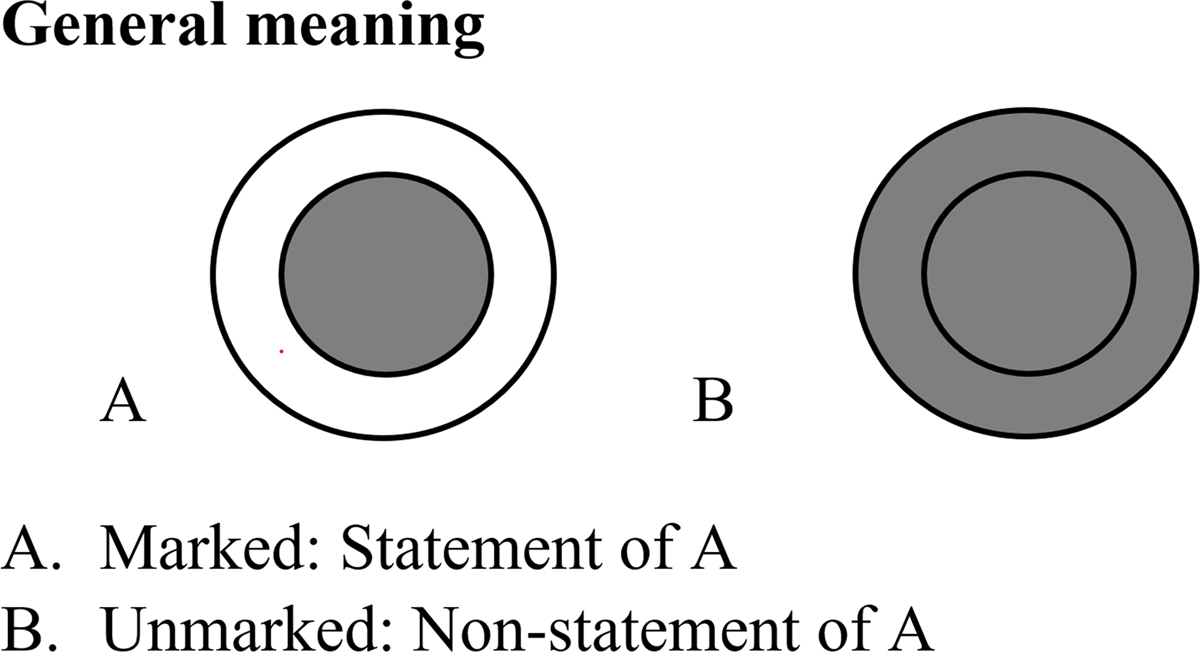

This idea was originally developed by Roman Jakobson in a series of articles, but in particular Jakobson (1957/1971). Andrews (1990) describes the original Markedness Theory proposed by Jakobson (1957/1971) thus: “The marked term gives the statement of a property A; the unmarked term can be divided into two components: (1) a general meaning = non-statement of A; (2) a specific meaning = statement of non-A” (Andrews, 1990, p. 10). The general meaning use is shown in Figure 13 below.

Jakobson’s theory of markedness with general meaning (Andrews, 1990, p. 10).

Horn’s Iconicity Principle states that (un)marked forms are mapped with (un)marked meanings (Grønn, 2007, p. 17). Therefore, meaning A would usually be expressed with a marked form. When “two morphological forms compete for the same semantic space (due to partial overlap in meaning) the more specific form may block the application of the less specific form wherever it can apply” (Hollenbaugh, 2019). Namely the hearer believes that there must be a reason the speaker used the specific form rather than the more general form, that is, the hearer expects that wherever the speaker can use the more specific form, the speaker will use the more specific form.

In historical Portuguese, the marked meaning of a resultative state (rather than an event) was most often represented with the marked form ter + participle which agrees with complement (marked form due to a higher morphological complexity), corresponding to meaning A in Figure 13 above. The -ra form was unmarked since it had a more general (larger range of) meaning and less complex morphology, corresponding to meaning B in Figure 13.

This situation of variation between the marked CPP and the unmarked -ra forms in the Portuguese pluperfect led to a delay in the semantic expansion of the former. Since the CPP originally had a more specific meaning (stative rather than eventive) it would have been reinforced in these contexts and disfavored in more general eventive interpretations. Since the CPP had this specific resultative interpretation available, the -ra forms would have been used less and less to express the same meaning because of the more specific available CPP form. Eventually, once the resultative meaning had given way to the eventive interpretation (seen in the sharp decline in participle–complement agreement in the CPP from the 17th century on), the CPP and the -ra forms overlapped in their use. It was not until the -ra form became restricted to formal written genres (ostensibly due to extra-linguistic factors dealing with language ideology and standardization of Portuguese since Galician maintains the -ra form) that the CPP generalized as the perfective-in-past. This process is called a markedness shift, where the originally marked (usually innovative) variant swaps places with the originally unmarked (usually traditional) variant, in this case the -ra form (Andersen, 2001). Visualized as the meanings in Figure 13, the CPP began as meaning A and the -ra forms as meaning B. As speakers generalized the CPP, that form became the unmarked (meaning B), leaving the -ra forms to be more restricted and only used in specific contexts for specific reasons (meaning A).

The exact opposite situation was found in the Spanish pluperfect. The use of the -ra form as a pluperfect indicative became marked since the -ra form was much more frequently used as a conditional/subjunctive by the 15th century. At this point, if a hearer heard a speaker use the -ra form, they would be forced to decide which meaning was intended. No such cognitive load would follow hearing a speaker use a CPP. Thus, the CPP was unmarked and the “better” form (“more economic; more harmonic; more salient etc.” (Grønn, 2008, p. 122)) to express the pluperfect.

Therefore, we see a different development between the Spanish and Portuguese CPP because between the 14th and 16th centuries, the marked Spanish -ra forms were increasingly blocked from occurring with the indicative pluperfect meaning since there was a more transparent option available (the CPP). During this same period, the marked Portuguese CPP was blocked from occurring with the perfective-in-past meaning until it lost the preference for resultativity (shown in participle–complement agreement). Simply put, the Spanish CPP generalized more quickly because it was the unmarked pluperfect form, and the Portuguese CPP took longer to generalize because it was originally the marked pluperfect form.

3.4. Summary

This section addressed the question of what role the generalization of auxiliary ter played in the development of the Portuguese pluperfect. Quantitative data from the Corpus do Português was collected to show that the generalization of ter was well established in both the CP and the CPP by the 16th century. It was then empirically shown that there was more participle–complement agreement in the constructions with ter than with haver, indicating a greater proportion of stative (i.e., resultative), rather than eventive, verbal meanings. This increased use of the resultative affected the CP and the CPP in different ways.