1. Introduction

External possession structures are found in most modern European languages (Nikolaeva 2002)1 and in many Bantu languages.2 Typically, they show up with transitive or unaccusative eventive verbs. These structures are puzzling insomuch as the constituent interpreted as the possessor is semantically dependent on the possessum, but exhibits the behavior of a syntactic dependent of the verb.

- (1)

- (a)

- Q:

- Partiste

- broke.1sg

- o

- the

- braço

- arm

- ao

- to.the

- João?

- João

- ‘Did you break João’s arm?’

- A:

- Sim,

- yes,

- parti-lhe

- broke-3sg.dat

- o

- the

- braço.

- arm

- ‘Yes, I broke his arm.’

- (b)

- Q:

- As-tu

- have-you.sg

- cassé

- broken

- le

- the

- bras

- arm

- à

- to.the

- Jean?

- Jean

- ‘Did you break Jean’s arm?’

- A:

- Oui,

- yes,

- je

- I 3sg.dat

- lui

- have

- ai

- broken

- cassé

- the

- le

- arm

- bras.

- ‘Yes, I broke his arm.’

The examples in (1) illustrate possessor dative structures (henceforth PDSs) in European Portuguese (henceforth, EP) and French, that is, structures where the possessor is either a dative clitic or a full DP introduced by the dative Case marker a/à and the possessum surfaces as the direct object of the verb.3 Importantly, the questions in (1) have as their paraphrases internal possession structures where the full DP preceded by a/à is spelled out as a genitive DP, introduced by de ‘of’: Partiste o braço do João?, As-tu cassé le bras de Marie?.

Comparative research on external possession structures led to the proposal of an acceptability hierarchy of possessors, with pronouns higher than full DPs (Payne & Barshi, 1999). Romance languages comply with this hierarchy, since possessors surfacing as full DPs introduced by the Dative Case marker are more restricted than dative clitics, as discussed below. In French, possessors surfacing as dative clitics are fine (2a), whereas PDSs with full DPs are ungrammatical (2b), internal possession being the only grammatical option (2c).4

- (2)

- (a)

- Le

- the

- médecin

- doctor

- lui

- 3sg.dat

- a

- has

- sauvé

- saved

- la

- the

- mère.

- mother

- ‘The doctor saved his/her mother.’

- (b)

- *Le

- the

- médecin

- doctor

- a

- has

- sauvé

- saved

- la

- the

- mère

- mother

- à

- to

- Jean.

- Jean

- (c)

- Le

- the

- médecin

- doctor

- a

- has

- sauvé

- saved

- la

- the

- mère

- mother

- de

- of

- Jean.

- Jean

- ‘The doctor saved Jean’s mother.’

Classical studies on PDSs in French (Kayne, 1975; Guéron, 1985; Vergnaud & Zubizarreta, 1992) highlighted the following two conditions on PDSs: (i) the relation between possessum and possessor should be one of parts-body; (ii) the possessor should be affected by the eventuality expressed by the verb. The first condition was quickly rephrased as one of inalienability between the possessum and the possessor. The second condition entailed not only that the possessor had to be sentient, hence typically human, but also that the verb had to be eventive, since affectedness usually involves change. These requirements on PDSs have generally prevailed in the literature on Romance languages, in spite of the amount of evidence collected meanwhile, which argues against this restricted view (see Kempchinsky, 1992; Lamiroy & Delbecque, 1998; Lamiroy, 2003; Pujalte, 2009; Miguel, Gonçalves & Duarte, 2011; Duarte & Oliveira 2018, a.o.; specifically for French, Rooryck, 1988, 2017; Authier & Reed, 1992; Boneh & Nash, 2012).5 A good example of this restrictive view is work by Cinque and Krapova (2008), where data which are not accounted for by the classical analysis are dismissed or else considered to be instances of some other construction.

On the other hand, in work on the Bantu language group dating back to the 1970s, external possession structures akin to possessor datives have also been described: the possessor is raised to object position, giving rise to a double object construction. According to Hyman (1977, p. 101), the syntactic process of possessor promotion or possessor raising “transforms the possessor into a direct object, if the verb is transitive” or, as we would put it nowadays, transforms the possessor into the primary object of the verb. This process is illustrated in (3) for Haya, and we will call the resulting structure the possessor double object construction (henceforth, PDOC).

- (3)

- ŋ-ka-hénd’

- 1sg-P3-break

- ómwáán’

- child

- ómukôno.

- arm

- ‘I broke the child’s arm.’

- Haya (J22), Hyman (1977, p. 100)

Almost a decade later, based on data from Kimenyi (1980) on Kinyarwanda, a north-eastern Bantu language, Massam (1985) distinguished two types of PDOCs: those where the relationship between possessor and possessum is alienable, and those where it is inalienable. She argues that the different behavior of the two structures with respect to some syntactic processes is a consequence of distinct derivations: in the former, the possessor remains inside the Theme DP, getting its Case externally from the verb “via the applied morpheme -ir-”, in a process akin to Exceptional Case Marking (ECM); in the latter, the possessor is moved before it is ECM’d to a peripheral position, where it receives “a kind of ‘floating’ dative case from the verb” (Massam, 1985, p. 337).

Massam’s proposal that a language may exhibit two different syntactic structures underlying PDOCs was later adopted by, for instance, Cinque and Krapova (2008) for Bulgarian and, more relevant for our purpose here, by Van de Velde (2020) for Bantu languages. He considers PDOCs nuclear or prototypical when possessor and possessum bear a body-part relation, and non-nuclear or applied when other possession relations obtain, although he does not propose a specific derivation for any of the structures. According to him, this distinction is expressed morphosyntactically in Bantu: “no applicative suffix can be used when the concern [our possessum] is an affected body part, whereas in other circumstances the use of the applicative may be either optional or obligatory” (Van de Velde, 2020, p. 11). The following examples from Chichewa and Tswana illustrate this difference:6

- (4)

- (a)

- Mphatso

- Mphatso

- a- na-thyol-a

- sm-pst-break-fv

- mwana

- child

- mwendo.

- leg

- ‘Mphatso broke the child’s leg.’

- (b)

- Tadala

- Tadala

- a- na-thyol-er-a

- sm-pst-break-appl-fv

- mwana

- child

- ndodo.

- stick

- ‘Tadala broke the child’s stick.’

- Chichewa, Simango (2007, p. 928)

- (5)

- (a)

- Ngw-ana

- 1-child

- o-tlaa-go-gat-a

- sm1-fut-om2sg-crush-fv

- letsogo.

- 5-hand

- ‘The child will crush your hand.’

- (b)

- Ngw-ana

- 1-child

- o-tlaa-go-j-el-a

- sm1-fut-om2sg-eat-appl-fv

- dinawa.

- 8/10.bean

- ‘The child will eat your beans.’

- Tswana, Creissels (2006, p. 108)

We will propose that the distinction between nuclear and non-nuclear also plays a role in Romance PDSs, based mainly on evidence from Portuguese.

In pursuing this goal, we aim at presenting a comparative survey of the range of variation found in Romance PDSs, whilst assessing the role of inalienability and affectedness in the light of the key distinction between nuclear and non-nuclear external possession structures in this language group. We will substantiate the claim that PDSs are subject to microvariation in Romance, like PDOCs in Bantu: in particular, we will argue that different values for a formal feature [ipart], indicating that the possessum bears a mereological relation with the possessor, distinguish nuclear from non-nuclear external possession structures in Romance (section 2.1). We will also follow Cuervo’s hypothesis that these structures express a “non-dynamic possession relation” (Cuervo, 2020, p. 16), hence that they share properties with ditransitive structures headed by give-type verbs. However, our implementation of this hypothesis will diverge from Cuervo’s proposal (section 2.2).

Our second goal is to provide a preliminary description of these structures in urban MozP. As far as we know, there is no work focusing on external possession structures in African varieties of Portuguese (AVPs) or on assessing the role of their contact languages. In order to do so, we will present and discuss MozP data extracted from the spoken corpus of the project Possession and Location: microvariation in African varieties of Portuguese (PALMA), as well as data collected in an exploratory elicitation task carried out in Maputo. The statistical analysis of the results confirm two emerging trends: a trend towards convergence with the VP structure of EP and a tendency towards transfer of the value for the [ipart] from Changana, with significant consequences for the nuclear/non-nuclear boundary (section 3).

Section 4 summarizes the main findings of this research.

2. Microvariation in Romance possessor dative structures

2.1 Nuclear and non-nuclear PDSs

In classical analyses of French, PDSs were restricted to inalienable possession relations, inalienability covering solely body-part relations and, by extension, items of clothing when the possessor is wearing them (e.g., Guéron, 1985).

The term ‘inalienable’ in these studies was not used in the sense it has in typology. In fact, in typological studies, the terms ‘alienable’ and ‘inalienable’ are labels which identify alternative morphological encodings of adnominal possession, that is, of internal possession. On the contrary, in studies on Romance, ‘inalienable’ is used to identify relations between possessum and possessor in external possession structures and goes back to Bally (1926), who built it on the loose notion of personal domain and on the logical property of indivisibility. In other words, objects and beings associated in an intimate way to a person (body and its parts, clothes, family, …) are an integral part of that person. This notion has an important conceptual consequence, namely, what counts as inalienable may differ from culture to culture and from language to language.

If one considers, along with Van de Velde (2020), that inalienable possession relations give rise to nuclear external possession structures, then the range of nuclear external possession structures will vary from language to language as a function of what counts as inalienable in the language. Particularly in what concerns us here, PDSs will show microvariation with respect to which types of possession relations count as inalienable, hence with respect to which PDSs are construed as nuclear. Suppose Romance languages draw the morphosyntactic distinction between nuclear and non-nuclear through the possibility vs. impossibility of PDSs with full DPs (introduced by the dative Case marker). Our hypothesis then predicts that when a nuclear PDS occurs in Romance, the possessor can occur as a full DP introduced by a dative Case marker or by a dative clitic. On the contrary, possessors in non-nuclear PDSs can only be spelled out as dative clitics.

We will test this hypothesis against data from French and EP. In French, “inalienability” excludes kinship and most ownership relations, so only body-part PDSs may be construed as nuclear, that is, either with full DPs introduced by the dative Case marker (à, ‘to’) or with dative clitics (see (1b), repeated here as (6)).

- (6)

- Q:

- As-tu

- have-you.sg

- cassé

- broken

- le

- the

- bras

- arm

- à

- to.the

- Jean?

- Jean

- ‘Did you break Jean’s arm?’

- A:

- Oui,

- yes,

- je

- I

- lui

- 3sg.dat

- ai

- have

- cassé

- broken

- le

- the

- bras.

- arm

- ‘Yes, I broke his arm.’

Instead, when ownership and kinship relations are at stake, PDSs with full DPs introduced by the dative Case marker are not accepted, as shown in (7).

- (7)

- (a)

- *Les

- the

- policiers

- policemen

- ont

- have

- fouillé

- searched

- les

- the

- poches

- pockets

- au

- to.the

- voleur. (ownership)

- robber

- (b)

- *Le

- the

- médecin

- doctor

- a

- has

- sauvé

- saved

- la

- the

- soeur

- sister

- à

- to

- Jean. (kinship)

- Jean

However, as pointed out by several authors referred to in section 1, the counterparts of (7) with dative clitics are fine (see (8)). According to our hypothesis, these are instantiations of non-nuclear PDSs in French.

- (8)

- (a)

- Les

- the

- policiers

- policemen

- m’ont

- 1sg.dat.have

- fouillé

- searched

- les

- the

- poches.

- pockets

- ‘The policemen searched my pockets.’

- Rooryck (2017, p. 2)

- (b)

- Le

- the

- médecin

- doctor

- lui

- 3sg.dat

- a

- has

- sauvé

- saved

- la

- the

- mère.

- mother

- ‘The doctor saved his/her mother.’

If we now consider the pairs in (9) and (10) in EP, differences in what counts as inalienable immediately emerge. Indeed, judgements on examples (9) contrast with the French examples in (7), since situations expressing ownership relations may give rise to nuclear PDSs in EP (9a) and judgements on nuclear PDSs with kinship relations are not as sharp as in French (9b). The corresponding examples with dative clitics in (10) are, as expected, fully grammatical.

- (9)

- (a)

- Os

- the

- polícias

- policemen

- revistaram

- searched

- os

- the

- bolsos

- pockets

- ao

- to-the

- ladrão.

- robber

- ‘The policemen searched the robber’s pockets.’

- (b)

- ?O

- the

- médico

- doctor

- salvou

- saved

- a

- the

- irmã

- sister

- ao

- to.the

- João.

- João

- ‘The doctor saved João’s sister.’

- (10)

- (a)

- Os

- the

- polícias

- policemen

- revistaram-lhe

- searched-3sg.dat

- os

- the

- bolsos

- pockets

- ‘The policemen searched his pockets.’

- (b)

- O

- the

- médico

- doctor

- salvou-lhe

- saved-3sg.dat

- a

- the

- irmã.

- sister

- ‘The doctor saved his sister.’

According to our hypothesis, example (9a) shows that inalienability extends to ownership relations in EP. In other words, entities such as clothes, cell phones, computers, glasses, pens, or cars are included in the personal domain of the possessor, hence the possessor may occur as a syntactic dependent of the verb in a nuclear PDS, as in (11a).

- (11)

- (a)

- O

- the

- miúdo

- kid

- estragou

- ruined

- o

- the

- telemóvel

- cell phone

- ao

- to.the

- Pedro.

- Pedro

- ‘The kid ruined Pedro’s cell phone.’

- (b)

- O

- the

- miúdo

- kid

- estragou-lhe

- ruined-3sg.dat

- o

- the

- telemóvel.

- cell phone

- ‘The kid ruined his cell phone.’

In contrast, acceptability judgements on PDSs conveying kinship relations show greater diversity (12a-13a), verb class being a factor that contributes to the acceptance or rejection of the structure. Thus, nuclear PDSs with transitive verbs (12a) are considered more degraded than those with unaccusative verbs (13a). Still, as predicted by our hypothesis, PDSs with dative clitics are grammatical (12b, 13b), that is, these qualify as non-nuclear PDSs.

- (12)

- (a)

- ??/*O

- the

- raptor

- kidnapper

- matou

- killed

- o

- the

- filho

- son

- ao

- to.the

- João.

- João

- ‘The kidnapper killed John’s son.’

- (b)

- O

- the

- raptor

- kidnapper

- matou-lhe

- killed-3sg.dat

- o

- the

- filho.

- son

- ‘The kidnapper killed his son.’

- (13)

- (a)

- ?Morreu

- died.3.sg.dat

- a

- the

- mãe

- mother

- ao

- to.the

- Pedro.

- Pedro

- ‘Pedro’s mother died.’

- (b)

- Morreu-lhe

- died-3sg.dat

- a

- the

- mãe.

- mother

- ‘His mother died.’

Indeed, if we consider unaccusative verbs, nuclear PDSs expressing both body/whole-part and ownership relations are fully accepted, as shown in (14) and (15), respectively.

- (14)

- (a)

- Caiu

- fell.3sg

- um

- one

- dente

- tooth

- ao

- to.the

- bebé.

- baby

- ‘One of the baby’s teeth fell out.’

- (b)

- Caiu-lhe

- fell-3sg.dat

- um

- one

- dente.

- tooth

- ‘One of his teeth fell out.’

- (15)

- (a)

- Desapareceu

- disappeared

- outra

- another

- vez

- time

- o

- the

- telemóvel

- cell.phone

- ao

- to.the

- João.

- João

- ‘João’s cell phone disappeared again.’

- (b)

- Desapareceu-lhe

- disappeared-3sgdat

- outra

- another

- vez

- time

- o

- the

- telemóvel.

- cell.phone

- ‘His cell phone disappeared again.’

Under our hypothesis that two types of PDSs are available in Romance languages and that these languages show microvariation dependent upon what counts as part of the personal domain of the possessor, the distribution of nuclear and non-nuclear PDSs in EP, in sentences with eventive verbs, is shown in Table 1 below.

Distribution of nuclear and non-nuclear PDSs with eventive verbs in EP.

| Verb classes | Eventive | |||

| Transitive | Unaccusative | |||

| PDS type | Nuclear | Non-nuclear | Nuclear | Non-nuclear |

| Body – part Whole – part | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Ownership | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Kinship | ??/*yes | yes | ?yes | yes |

Up to now, we have been considering the property of inalienability in Romance PDSs. But in the classical studies on external possession structures, another property was taken to be a requirement on external possession structures: affectedness.

Affected arguments of a verb refer to conscious, sentient entities causally changed (in a broad sense) by the eventuality the sentence describes (see Hole, 2005, p. 220). Under this definition, affectedness is a property restricted to human entities – at the very best, extended to some animals.

Indeed, affectedness seems to be a mandatory condition on PDSs in French, as its violation results in ungrammatical sentences independently of the form of the possessor: dative clitic (16a) or full DP introduced by the dative Case-marker (16b).

- (16)

- (a)

- *La

- the

- table,

- table

- je

- I

- lui

- 3sg.dat

- ai

- have

- astiquée

- polished

- toute

- whole

- la

- the

- surface.

- surface

- Van de Velde & Lamiroy (2017, p. 369)

- (b)

- *J’ai

- I have

- repeint

- repainted

- les

- the

- murs

- walls

- à

- to

- la

- the

- maison

- house

- de

- of

- mes

- my

- parents.

- parents

Again, this requirement is subject to variation in Romance. Thus, nuclear PDSs with unaffected possessors are grammatical in Western Romance languages, as shown in (17) for Spanish and in (18) for EP.

- (17)

- (a)

- Marta

- Marta

- le

- 3sg.dat

- arrancó

- tore

- una

- a

- página

- page

- al

- to.the

- libro.

- book

- ‘Marta tore a page out of the book.’

- Kempchinsky (1992, p. 136)

- (b)

- Le

- 3sg.dat

- fregué

- wiped

- las

- the

- manchas

- stains

- al

- to.the

- tablero.

- table

- ‘I wiped the stains off the table.’

- Demonte (1995, p. 23)

- (18)

- (a)

- O

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- lavou

- washed

- os

- the

- vidros

- windows

- ao

- to.the

- carro

- car

- e

- and

- aspirou-lhe

- vacuumed-3sg.dat

- a

- the

- bagageira.

- trunk

- ‘Pedro washed the car windows and vacuumed its trunk.’

- (b)

- Já

- already

- caíram

- fell

- pétalas

- petals

- às

- to.the

- rosas.

- roses

- ‘Petals have already fallen off the roses.’

Moreover, the concept of affectedness entails that only eventive verbs occur in PDSs. Although this seems to be the case for French, as the ungrammaticality of (19) illustrates, Western Romance languages and even Italian exhibit PDSs with non-eventive verbs, as illustrated in (19) to (23) below.7 However, except for Spanish, only non-nuclear PDSs – that is, PDSs restricted to dative clitic possessors –, are possible in Catalan, Italian, and EP.

- (19)

- *Je

- I

- lui

- 3sg.dat

- ai vu

- have seen

- le visage/la maison.

- the face/the house

- Lamiroy (2003, p. 2)

- (20)

- Pablo

- Pablo

- le

- 3sg.dat

- miró/estudió/observó

- saw/studied/observed

- los

- the

- pies

- feet

- a

- to

- Valeria.

- Valeria

- ‘Pablo saw/studied/observed Valeria’s feet.’

- Spanish, Cuervo (2003, p. 84)

- (21)

- Encara

- yet

- no

- not

- li

- 3sg.dat

- conec

- know

- la

- the

- dona.

- wife

- ‘I do not know his wife yet.’

- Catalan, Picallo & Rigau (1999, p. 1016)

- (22)

- Le

- 3sg.dat

- ho

- have

- visto

- seen

- le

- the

- gambe.

- legs

- ‘I have seen her legs.’

- Italian, Cinque & Krapova (2008, p. 68)

- (23)

- (a)

- *Agora

- now

- já

- already

- conheço

- know

- os

- the

- defeitos

- flaws

- ao

- to.the

- Pedro.

- Pedro

- (b)

- Speaking about Pedro:

- Agora

- now

- já

- already

- lhe

- 3sg.dat

- conheço

- know

- os

- the

- defeitos.

- flaws

- ‘Now I am aware of his flaws.’

Non-eventive verbs do not affect their Theme argument, as the sentences describe states, that is, eventualities where none of the entities referred to by the relevant DPs suffer any type of change (either change of state, place, or possession).8 Thus, data like those in (19) to (23) again show that the requirement of affectedness is subject to variation in Romance, as many authors have remarked (e.g., Dumitrescu, 1990; Lamiroy, 2003; Cuervo, 2003, 2020). Indeed, it further suggests that affectedness of the external possessor is not a consequence of theta-assignment (Henderson, 2014) or, more importantly, that it is not structurally encoded in PDSs. We will get back to this issue in section 3.

2.2. The formal features [ipart] and [uposs]

In the remainder of the section, we will try to answer two questions about the data from EP. The first question concerns the way grammar copes with the variation in the concept of the personal domain, either restricting or widening the property of inalienability, which, as we argued, has a direct bearing on the distinction between nuclear and non-nuclear PDSs.

Our answer to this question is built upon the proposal in Baker (1996, 1999) to account for the licensing of structures akin to PDSs in the polysynthetic language Mohawk. He considers that body-part nouns and other nouns share an argument structure containing an R-argument (Williams, 1981) and a possessor argument. The difference between them, he claims, is that the latter is obligatory in body-part nouns (Ri, Poss’ri) while it is optional in all the other nouns (Ri, (Poss’ri)), where its presence depends on cultural factors. Baker’s proposal circumvents the problems of other accounts which consider that the licensing of external possession structures depends upon possessa being relational nouns. Indeed, as abundantly illustrated above, in many Romance languages, body parts license possessor datives freely but other relational nouns denoting parts or kinship do not. Capitalizing on Baker’s proposal, we propose that nuclear PDSs depend on the presence of the formal feature [ipart: yes] in the possessum noun, whereas the value ‘no’ for this formal feature can only yield non-nuclear PDSs. We assume that this feature is indeed obligatory in body parts, but its presence in other nouns referring to physical objects is constrained by cultural aspects, specific to each language community, and encoded in the lexicon. In this sense, we consider the assignment of this feature value to nouns that do not refer to body parts a case of what Hale (1986) calls World View-2, that is, a property “embodied in the system of lexico-semantic themes or motifs which function as integral components in a grammar (…).” (Hale, 1986, p. 234). Thus, if [ipart: yes] is not present in the possessum noun, only a non-nuclear PDS can be derived (or else an internal possession structure).

This analysis accounts for the microvariation found in Romance PDSs. Thus, in French, [ipart: yes] is only present in body parts nouns denoting entities that can be affected (and in items of clothing in contact with the possessor’s body), hence the range of nuclear PDSs in this language is very restricted. On the contrary, in EP, as well as in other Romance languages like Spanish (e.g., Kempchinsky 1992), nuclear PDSs are less restricted, as [ipart: yes] is also present in nouns which are parts of wholes, as well as in many nouns denoting physical objects included in the personal domain, but not in relational kinship nouns in general. We therefore propose that the possessum constituent in a nuclear PDS enters the derivation with the following property: the possessum N has the sublabel [ipart: yes]. However, both in French and in the other Romance languages considered here, non-nuclear PDSs also occur, where the possessor can only surface as a dative clitic. These are cases where the possessum noun is merged from the lexicon with the formal feature [ipart: no].

The second question we need to address is the structure of the VP where both possessum and possessor are first merged. Since the 1980s, several analyses have sought to bring together Romance PDSs and sentences with secondary predication domains. Thus, it has been proposed that the constituent containing possessum and possessor is a predication domain, although proponents of this approach do not share the same view with respect to the category of the head (e.g., for French, Guéron, 1985; Rooryck, 2017; for Spanish, Sanchez, 2007; for EP, Miguel, 2004; Miguel, Gonçalves & Duarte, 2011). Some of these authors, elaborating on work by Freeze (1992) and den Dikken (2006), consider that the possession relation is encoded syntactically as a locative predication. Others, seeking a syntactic structure generalizable to “partitives, inalienable and alienable possession, and also the notion of location” (Manzini & Franco, 2016), consider that the possession relation in Romance and in many other languages is encoded in syntax by means of the inclusion operator (⊆); this operator, a subtype of category P or Q, would select the possessum constituent, which would also present the sublabel [+ ⊆].

Our proposal that [ipart: yes] in nuclear PDSs is a sublabel of the possessum DP, as well as of the head that selects it, is in line with Manzini & Franco’s proposal, with the added benefit that it circumvents the inadequacy of treating the part-whole relation as a subset relation.9 Besides, we do not adopt their proposal of a new category ‘inclusion’ in the catalogue of syntactic heads available for Merge operations of the CHL. Instead, we consider that the head of the small clause in PDSs is of D or Q category.

In short, we also adopt the idea that the Theme DP in Romance PDSs is merged as a small clause, although departing from the analyses that consider it a locative predication. Instead, we follow Cuervo’s (2003, 2020) hypothesis that external possession structures in Romance express a “non-dynamic possession relation” (Cuervo, 2020: 16). However, we do not follow her use of low and high applicative heads for the analysis of nuclear and non-nuclear PDSs in Romance.

In fact, Cuervo (2020) considers that in the derivation of PDSs expressing body/whole-part relations a low applicative head, LowApplAT, selects a DP (the possessum), the possessor being the applied argument. However, as argued elsewhere with respect to core datives (see Gonçalves, Duarte & Hagemeijer, 2022), Portuguese as well as other Romance languages lack dedicated applicative morphology, whereas Bantu languages, for instance, exhibit overt applicative morphology in the verb structure to encode optional arguments and adjuncts as core-objects (Peterson, 2007; Polinsky, 2013). An additional empirical argument against the use of applicatives in the analysis of nuclear PDSs in Romance comes from Bantu languages which do not resort to applicative heads in the derivation of nuclear PDOCs (see section 3).

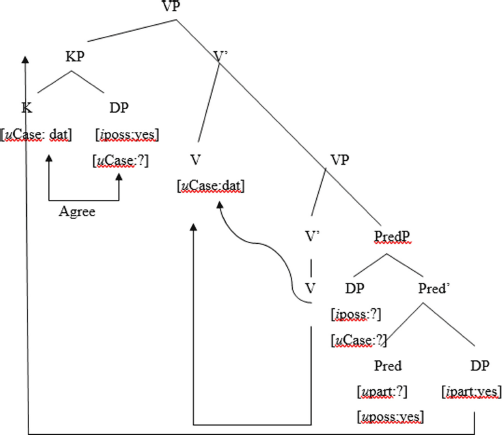

Hence, we implement Cuervo’s (2003, 2020) idea that PDSs express a non-dynamic possession relation with the help of a second sublabel, present in the head of the predication domain hosting both the possessum and the possessor, namely the feature [uposs(essor): yes], which must be valued through local agree. The possessor, endowed with the feature [iposs: ?], moves to the edge of the small clause for valuation purposes. Therefore, we assign the substructure presented in (24) to the predication domain of a nuclear PDS selected by transitive Vs.

- (24)

The representation in (24) has the form of a Larsonian shell, that is, a VP with an extra V-layer. We take the nodes labelled as ‘Pred’ to be of category D or Q, as stated before. The possessum DP must move upwards to a position where its Case feature gets valued by v. Suppose the upper V is the locus of dative Case valuation in Romance, by allowing a KP to occur in its Spec, or a clitic to Head-move to this position. The upper V, endowed with the sublabel [uposs:?] attracts the possessor DP to value this feature. If the possessor is a clitic, assuming clitics are D’s, the clitic further Head-moves to v for independent reasons. Due to MLC, the upper V first attracts the possessor DP, and only then movement of the possessum DP to value accusative Case in Spec, Voice follows.10

The VP structure of non-nuclear PDSs differs minimally from the one in (24). We claim that, in this case, as the possessum is first merged with the formal feature [ipart:no], the possessor is a constituent that exhaustively dominates a clitic head. Hence, there is no Spec position available in the upper VP which might host a full DP.

Thus, contrary to classical analyses of PDSs in Romance, our analysis of nuclear and non-nuclear PDSs in EP involves movement of the possessor. However, it is in line with other analyses which also claim that the possessor DP moves out of the V complement (e.g., Landau, 1999 for Hebrew; Sanchez, 2007 for Spanish; Henderson, 2014 for Chimwiini).11

With this partial derivation in mind, we can now address the similarities between PDSs and ditransitive structures with give-type verbs. Both have a Larsonian VP shell, as both involve complex predicate structures in the sense of Marantz (1993), Pesetsky (1995), or Bruening (2001) and, in both, the locus of dative Case is the upper V. Furthermore, according to our analysis, structures headed by give-type verbs and PDSs share another property, the formal feature [uposs: yes] as a sublabel of the relevant predicate (Gonçalves, Duarte & Hagemeijer, 2022): V in the former, D/Q in the latter. Hence, [uPoss: yes] in give-type verbs accounts for the transfer of possession relation between Theme and Goal arguments (Gonçalves, Duarte & Hagemeijer, 2022), whilst [uPoss: yes] in the D/Q predicate of the small clause in PDSs accounts for the non-dynamic possession relation established between possessum and possessor.

However, as is well known, the striking difference between PDSs and sentences with give-type verbs lies in the fact that in the former the dative constituent is not theta-dependent on the verb, whereas in the latter it is.

3. PDSs in Mozambican Portuguese – a first sketch

Mozambican Portuguese (henceforth MozP) has been at the core of research on emergent African varieties of Portuguese (henceforth AVPs) since the 1990s, in extensive work by P. Gonçalves (1991, 2002, 2004, 2010). However, although ditransitive structures with give-type verbs have been widely addressed, as far as we know, there is no work focusing on external possession structures in this or other AVPs.

Maputo MozP is historically in contact with Changana, also referred to as Xichangana,12 a Bantu language of the Tswa-Ronga group (Guthrie’s Code Number S53).13 This historical situation of contact between MozP and Changana can be traced back to the last decade of the 15th century and is currently attested in Maputo, where an increasing number of speakers have Portuguese as their L1 or L2. Indeed, according to the 2017 Mozambican national census, Changana is spoken as L1 by 1,919,217 people over five years of age; in turn, MozP is spoken as L1 by 3,686,890 people over five years of age (INE 2019), especially in urban areas and the capital Maputo in particular.

The first kind of data we will discuss in this section is based on a spoken subcorpus of urban corpora from three African varieties of Portuguese (Angolan, Santomean, and Mozambican Portuguese) that were prepared within the PALMA project (1,154,265 tokens, see Hagemeijer et al. 2022). The MozP corpus comprises 70 semi-structured interviews, which correspond to 42 hours of recording and 423,344 tokens. It was collected between 2010 and 2020 by researchers of the Center of Linguistics of the University of Lisbon in the capital Maputo, and it was as much as possible calibrated according to level of education, age, and sex. The speakers are monolingual in Portuguese or bilinguals in Portuguese and a Bantu language, with Changana standing out.

A corpus search for MozP PDSs was carried out on the CQPweb platform; the search targeted transitive and unaccusative verbs, as well as the type of possession relation between possessor and possessum (body-part, ownership, and kinship). Although infrequent, PDSs are attested in the analyzed urban MozP oral corpus. The utterances below describe body-part (see (25)) and ownership (see (26)) situations with the following transitive verbs: bater ‘hit’; cortar ‘cut’; partir ‘break’; pegar ‘take’; and tirar ‘take away’.14

- (25)

- (a)

- … amarrou-me

- tied-1sg.dat

- os

- the

- pés,

- feet,

- amarrou

- tied

- [-]

- [-]

- na

- in.the

- corrente.

- chain

- ‘He tied my feet, tied them with a chain.’

- (b)

- se

- if

- eu

- I

- te

- 2sg.dat

- cortasse

- cut.subj

- o

- the

- coração

- heart

- agora, …

- now

- ‘If I would cut your heart now, …’

- (c)

- então

- so

- disse

- said.3.sg

- que

- that

- partiram-lhe

- broke-3sg.dat

- a

- the

- costela

- rib

- ‘So he said that they broke his rib.’

- (d)

- peguei-lhe

- took-3sg.dat

- a

- the

- mão,

- hand

- começámos

- started

- a

- to

- correr…

- run.inf

- ‘I took her hand, we started to run…’

- (e)

- ele

- he

- até

- even

- nem

- not

- conseguiu

- managed

- bater-me

- hit.inf-1sg.dat

- bem

- well

- o

- the

- pé.

- foot

- ‘He was not even able to hit my foot well.’

- (26)

- (a)

- umas idosas (…)

- some oldies

- que

- whom

- estão

- are

- a

- to

- lhes

- 3pl.dat

- tirar

- take_away

- a

- the

- terra

- land

- para

- to

- construir

- build

- condomínios.

- condos

- ‘some old ladies whose land is being taken away to build condos.’

- (b)

- Como

- as

- me

- 1.sg.dat

- castigaram,

- punished,

- tiraram-me

- took-1sg.dat

- toda

- all

- a

- the

- roupa.

- clothes

- ‘As they punished me, they took off all my clothes.’

Importantly, of the dozen PDSs attested in the corpus, none displayed possessors spelled out as full DPs introduced by the dative Case marker. Moreover, the few cases of PDSs with a possession relation other than body/whole-part found in the corpus suggest that this type of external possession structure is infrequent in urban MozP.

However, we revised this conclusion, as informants let us know that sentences like the ones in (27) are often heard in this variety.

- (27)

- (a)

- Este

- this

- bêbado

- drunkard

- bateu-lhe

- hit-3sg.dat

- o

- the

- carro.

- car

- ‘This drunkardi hit his/herj car.’

- (b)

- O

- the

- miúdo

- kid

- riscou-me

- scratched-1sg.dat

- o

- the

- carro.

- car

- ‘The kid scratched my car.’

- (c)

- O

- the

- amigo

- friend

- está

- is

- a

- to

- comer-lhe

- eat-3sg.dat

- a

- the

- mulher.

- woman

- ‘Hisi friend is f*ing hisi wife.’

Again, in all the data provided by our informants, the possessor is expressed by a dative clitic. Moreover, no external possession structures have been attested in the corpus with unaccusative verbs. Further, PDOCs were not attested in MozP, although DOCs are found in this variety with core ditransitive structures (e.g., P. Gonçalves, 1991, 2002, 2004, 2010; Gonçalves, Duarte & Hagemeijer, 2022).

The data above point toward a more restricted use of external possession structures in MozP than in EP, as well as to a different set of conditions these structures comply with. The first hypothesis that comes to mind with respect to the non-convergence with EP is the influence of the grammar of Bantu languages spoken in the Maputo area, in particular, Changana.

Changana displays external possession structures with the form of PDOCs, where the possessor precedes the possessum. As Chimbutane (2002, pp. 108–109) points out, two postverbal NPs may follow the verb in sentences with “inherently monotransitive verbs (…) describing situations in which one of the postverbal NPs represents the possessor and the other a part of such a possessor” (see (28)).15

- (28)

- (a)

- Juwawa

- Juwawa

- a-tshov-ile

- 1sm-1om-break-pst

- Pedru

- Pedru

- voko.

- 5.arm

- ‘Juwawa broke Pedru’s arm.’

- (b)

- Juwawa

- Juwawa

- a-hlampsi-ile

- 1sm-wash-pst

- Mariya

- Mariya

- mi-sisi.

- 4-hair

- ‘Juwawa was washing Mariya’s hair.’

Thus, in sentences describing body/whole part relations, a DOC structure with the possessor as the primary object occurs; these are instances of nuclear PDOCs.

However, when an ownership relation is at stake, Changana must resort to the grammatical process available in many other Bantu languages for licensing non-nuclear external possession structures: the introduction of an applicative head, -el-, as shown in (29), a sentence where the constituent referring to the possessor is foregrounded and behaves as a syntactic dependent of the verb.16

- (29)

- Mufana

- 1.boy

- a-davul-el-ile

- 1SM-tear-appl-pst

- n’wana

- 1.child

- banci.

- 5.shirt

- ‘The boy tore the child’s shirt.’ (while he was not wearing it)

Summarizing, Changana exhibits both nuclear (without applicative head) and non-nuclear (with applicative head) PDOCs. The former are restricted to body/whole part while the latter show up with ownership possession relations. This clearly contrasts with EP, where, as it was shown, nuclear PDSs are extended to situations expressing ownership relations. Moreover, EP and Changana also differ in the VP structure, since only the latter exhibits PDOCs. However, both allow the possessor to be recovered, either by a dative clitic, in EP, or by prefixation to the verb root, in Changana, as shown in (30).

- (30)

- (a)

- Juwawa

- Juwawa

- a-mu-tshov-ile

- 1sm-1om-break-pst

- voko

- 5.arm

- (, Pedru).

- Pedru

- ‘Juwawa broke his arm (,Pedru’s arm).’

- (b)

- Juwawa

- Juwawa

- a-mu-hlampsi-ile

- 1sm-1om-wash-pst

- mi-sisi

- 4-hair

- (, Mariya).

- Mariya

- ‘Juwawa washed her hair (, Mariya’ s hair).’

In order to overcome the infrequency of external possessor structures attested in the urban MozP corpus, as well as to assess the role played by contact with Changana, we designed an exploratory Acceptability Judgement Task, which was applied in Maputo. This task included three factors, taken as independent variables, and the spell out of the possessor (as a full a DP, a dative clitic, or a DP in a DOC), taken as a dependent variable.

In what concerns the spell out of the possessor, we aimed to find out whether MozP behaves as EP, where the possession relation body/whole-part or ownership has no bearing on the acceptability of a full DP introduced by the dative Case-marker. Additionally, as Changana exhibits PDOCs, we wanted to assess the acceptability of these VP structures in MozP, to obtain evidence with respect to the role of language contact.

As for the three factors considered in the elicitation task, the type of possession relation seemed to us of particular relevance. As shown, Changana exhibits two distinct PDOCs, depending on whether the sentence describes a body/whole-part relation (nuclear PDOCs, without an applicative head) or an ownership one (non-nuclear PDOCs, with an applicative head), differently from EP. If MozP converges with the target grammar, i.e. EP, it is expected that no difference is observed between the sentences describing body/whole-part and ownership possession relations. On the other hand, if MozP tends to converge with Changana, it is expected that, in PDSs with ownership possession relations, full DPs introduced by the dative Case marker are excluded.

A second factor we considered was the interpretation of the possessor as malefactive or benefactive, because our informants informed us that sentences containing Changana non-nuclear PDOCs are ambiguous between a PDOC reading and a benefactive/malefactive DOC reading of the foregrounded constituent (see (31a) and (31b)).

- (31)

- (a)

- Mamani a-hlamps-el-ile

- 1.mother 1SM-wash-appl-pst

- n’wana

- 1.son

- wakwe

- poss

- mimeya. (kinship)

- 4.sock

- Int 1: ‘Mommy washed her son’s socks.’

- Int 2: ‘Mommy washed the socks for the benefit of her son.’

- (b)

- Juwawa

- Juwawa

- a-fay-el-ile

- 1sm-break-appl-pst

- Pedru

- Pedru

- wachi (ownership)

- 5.watch

- ‘Juwawa broke Pedru’s watch / Juwawa broke the watch to the detriment of Pedru.’

So, if the ambiguity exhibited by Changana with non-nuclear PDOCs were also present in MozP, acceptability scores for partir ‘break’ and lavar ‘wash’ would be different, depending on how high the informants rate the beneficiary or the maleficiary readings.

The third factor we considered was the schooling level of the subjects, as more years of schooling normally imply more access to the target language. In fact, studies on morphosyntactic features of AVPs generally conclude that schooling leads to increased convergence with EP. Although we were aware that PDSs with a DP would be scarce, if any, in the input of the informants and, additionally, that this type of structures is not the object of explicit instruction, we still decided to consider the schooling level. Therefore, the elicitation task was applied in Maputo to 56 informants, divided in two groups of 28, according to schooling level. The informants of group SEC (17 years old, on average) were students from a Maputo high school, whereas those from group UNIV (23 years old, on average) were university students. If schooling level played a role in the grammar of PDSs, we would expect students from the SEC group to present an acceptance pattern which converges less with EP than that of the UNIV group.

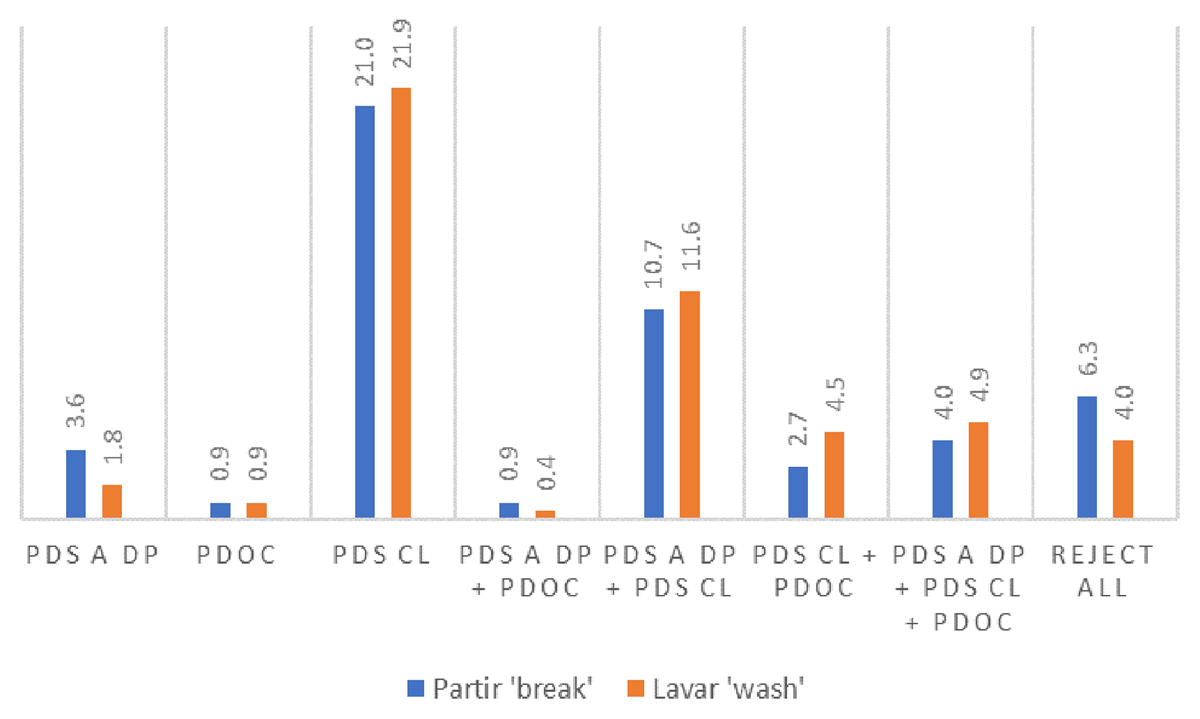

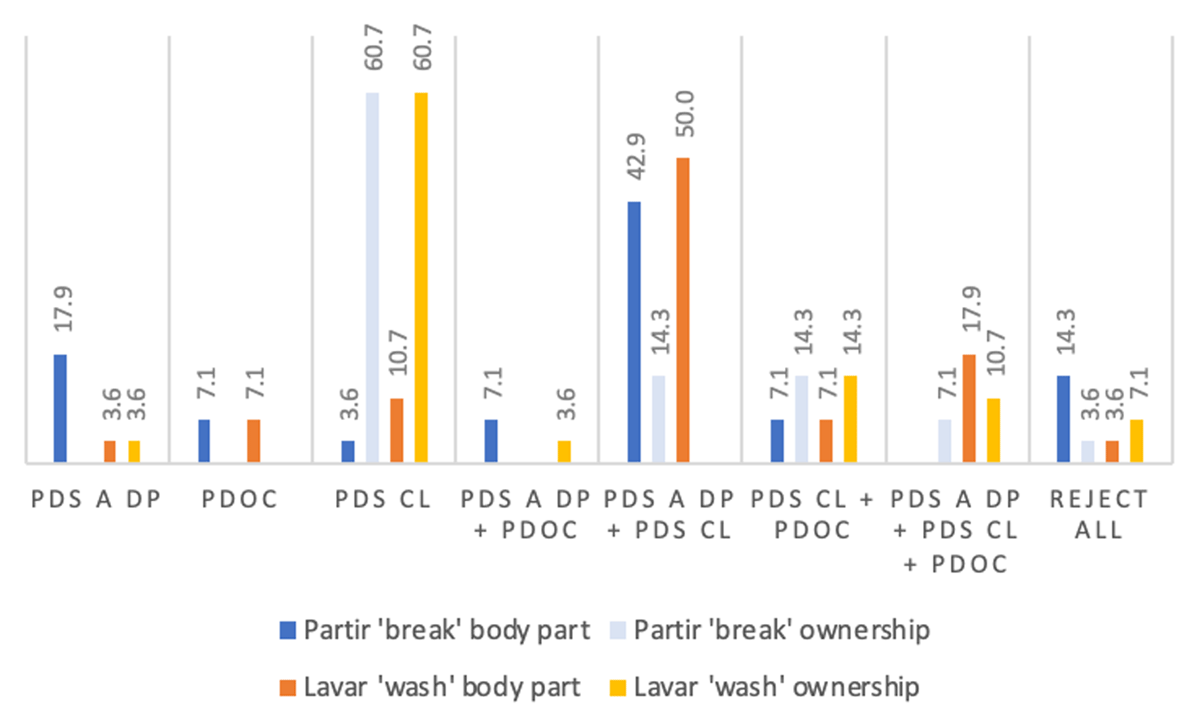

The results for the form of the possessor (PDSs with full DPs introduced by the dative Case marker, henceforth a DPs, PDSs with a dative clitic, henceforth PDSs CL, and/or PDOC) are shown in Figure 1, where the numbers represent the percentage of each of the forms out of the total test items (N. 224) (accepted and rejected) by both groups. Results are organized by subclass of the transitive verb (partir ‘break’ and lavar ‘wash’).

As the data underscores, the higher number of accepted items corresponds to PDSs with clitics, with percentages ranging from 21.0% to 21.9%, respectively for the verb partir ‘break’ and lavar ‘wash’ (cf. (45–46)).

- (45)

- (a)

- Ontem,

- yesterday,

- o

- the

- João

- João

- chocou

- bumped

- com

- into

- o

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- e

- and

- partiu-lhe

- broke-3sg.dat

- o

- the

- braço.

- arm

- ‘Yesterday, João bumped into Pedroi and broke hisi arm.’

- (b)

- As

- the

- crianças

- children

- estavam

- were

- a

- at

- brincar

- play.inf

- com

- with

- o

- the

- avô

- granddad

- e

- and

- partiram-lhe

- broke-3sg.dat

- os

- the

- óculos.

- glasses

- ‘The children were playing with their granddad and broke his glasses.’

- (46)

- (a)

- A

- the

- criança

- child

- chegou

- arrived

- muito

- very

- suja

- dirty

- e

- and

- a

- the

- mãe

- mother

- lavou-lhe

- washed-3sg.dat

- as

- the

- mãos

- hands

- e

- and

- a

- the

- cara.

- face

- ‘The child got home very dirty and his/her mother washed his/her hands and face.’

- (b)

- Para

- to

- ajudar

- help

- o

- the

- primo,

- cousin,

- o

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- lavou-lhe

- washed-3sg.dat

- o

- the

- carro.

- car

- ‘In order to help his cousini, Pedro washed hisi car.’

The category corresponding to informants who accept both PDSs with a DPs as well as dative clitics was the one with the second highest rates, with percentages of respectively 10.7% and 11.6% for partir ‘break’ and lavar ‘wash’ (cf. (47–48)). Moreover, the acceptability of PDSs with a DPs exclusively is quite marginal (3.6% with partir ‘break’, and 1.8% with t lavar ‘wash’).

- (47)

- (a)

- O

- the

- jogador

- player

- deu

- gave

- um

- a

- pontapé

- kick

- com tanta

- with such

- força

- strength

- que

- that

- partiu

- broke

- um

- a

- dedo

- finger

- ao

- to.the

- guarda-redes.

- goalkeeper

- ‘The player’s kick was so strong that he broke one of the goalkeeper’s fingers.’

- (b)

- O

- the

- nosso

- our

- filho

- son

- faz

- makes

- muitas

- many

- asneiras;

- blunders;

- ontem

- yesterday

- partiu

- broke

- o

- the

- relógio

- watch

- ao

- to.the

- pai.

- father

- ‘Our son screws up a lot; yesterday he broke his father’s watch.’

- (48)

- (a)

- Antes de

- before

- irem

- go.3.pl.inf

- comer,

- eat.inf,

- a

- the

- Ana

- Ana

- lavou

- washed

- as

- the

- mãos

- hands

- ao

- to.the

- irmão

- brother

- mais

- more

- novo.

- young

- ‘Before eating, Ana washed her younger brother’s hands.’

- (b)

- Quando

- when

- chegou,

- arrived,

- a

- the

- mãe

- mother

- lavou

- washed

- as

- the

- meias

- socks

- ao

- to.the

- filho.

- son

- ‘When she got home, the mother washed her son’s socks.’

In what concerns PDOCs, the most important observation arising from the data is that informants who accept PDOCs also accept PDSs with both a DPs and the dative clitic. The acceptability of both PDOCs and PDSs is respectively 4.0% and 4.9% for transitive verbs partir ‘break’ and lavar ‘wash’, showing its marginal availability. With percentages as lows as 0.4%, with the verb lavar ‘wash’ and 0.9% with the verb partir ‘break’, the acceptability of both PDOCs and PDSs with a DPs is almost inexistent; also, the acceptability of both PDOCs exclusively is extremely low, independently of the transitive verb (0.9%).

- (51)

- (a)

- Apareceu

- showed-up

- um

- a

- carro

- car

- a

- at

- toda

- all

- a

- the

- velocidade

- speed

- e

- and

- partiu

- broke

- o

- the

- meu

- my

- irmão

- brother

- as

- the

- pernas.

- legs

- ‘A car showed up at full speed and broke my brother’s legs.’

- (b)

- Os

- the

- bandidos

- bandits

- roubaram

- robbed

- o

- the

- dinheiro

- money

- e

- and

- partiram

- broke

- o

- the

- homem

- man

- o

- the

- computador.

- computer

- ‘The bandits stole the man’s money and broke his computer.’

- (52)

- (a)

- Antes

- before

- de lhe

- 3sg.dat

- pôr

- apply.inf

- um

- a

- adesivo,

- patch,

- o

- the

- treinador

- coach

- lavou

- washed

- o

- the

- jogador

- player

- a

- the

- testa.

- forehead

- ‘Before applying a patch, the coach washed the player’s forehead.’

- (b)

- O

- the

- Pedro

- Pedro

- lavou

- washed

- o

- the

- avô

- granddad

- o

- the

- boné,

- cap,

- que

- which

- estava

- was

- muito

- very

- sujo.

- dirty

- ‘Pedro washed his granddad’s cap, which was very dirty.’

Finally, it is worth noting that a few subjects reject every possessor form for one of the verbs (6.3% with partir ‘break’ and 4.0% with lavar ‘wash’), although no speaker rejects every possessor form for both verbs.

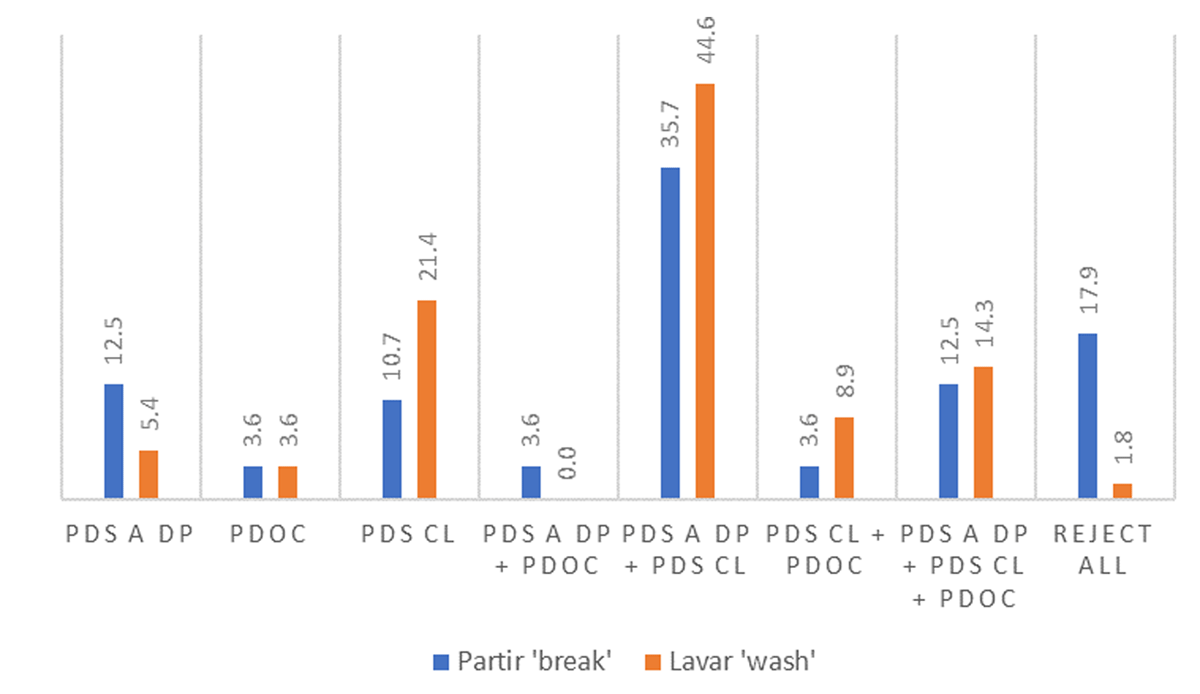

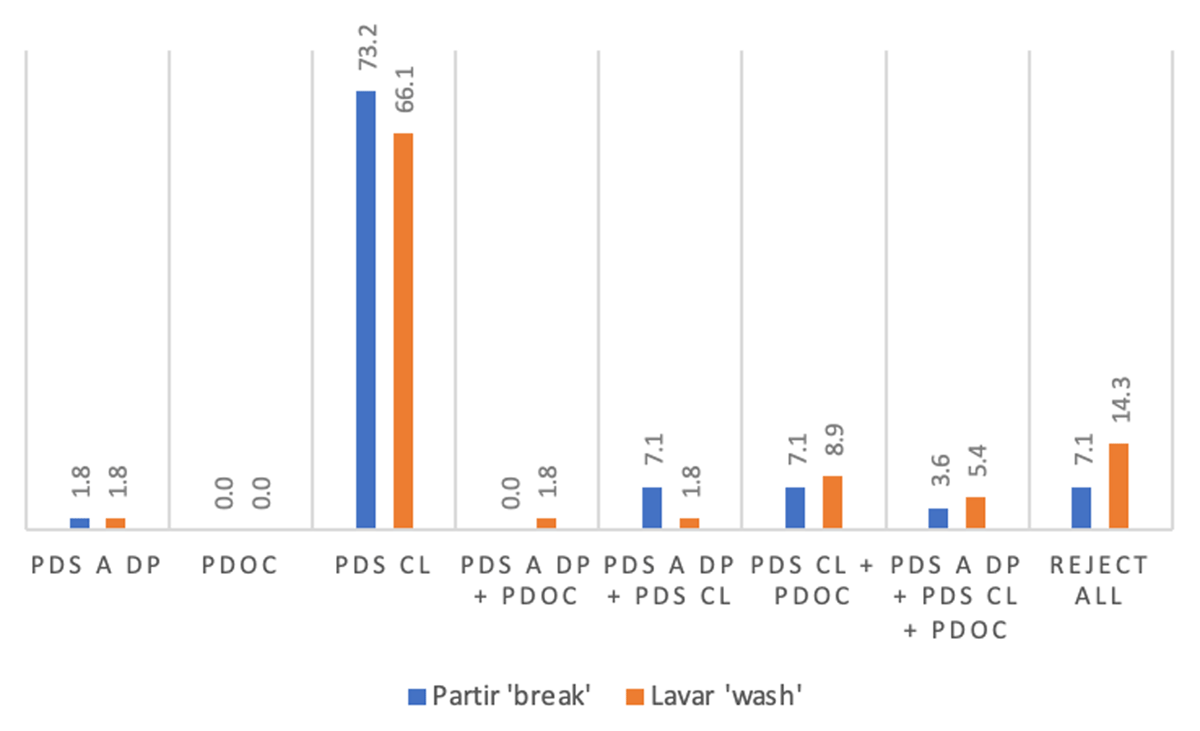

Let us now consider the results by possession relation (body-part vs. ownership). Figures 2 and 3 present the data organized by subclass of transitive verb (partir ‘break’ vs. wash ‘lavar’) and the possession relation. The numbers in the figures represent the percentage of informants out of the total (N. 56) that either accepted or rejected the test items.

Two main observations arise from the data. First, as Figure 2 shows, when the body-part relation is at stake, a higher percentage of informants accept PDSs with both a DP and dative clitics, with percentages of respectively 35.7% (partir ‘break’) and 44.6% (lavar ‘wash’). There is also a group of informants that prefer PDSs with a dative clitic, with a higher preference for the transitive verb lavar ‘wash’ (21.4%), contrasting with 10.7% for partir ‘break’. Also, some informants accept both PDSs (with a DPs and dative clitics) and PDOCs (12.5% and 14.3% for each transitive verb), which could indicate responses given by chance or else instability in the internal grammar of these speakers; however, as shown in Figure 3, these rates are considerably lower (3.6% and 5.4% for each transitive verb) when the ownership relation is at stake. Second, considering the ownership relation, the dative clitic is the most accepted possessor form with both transitive verbs, with scores of respectively 66.1% (lavar ‘wash’) and 73.2% (partir ‘break’). Moreover, not only are PDOCs rejected by every subject, but also PDSs which occur exclusively with a DPs show very low levels of acceptance (1.8% for each verb).

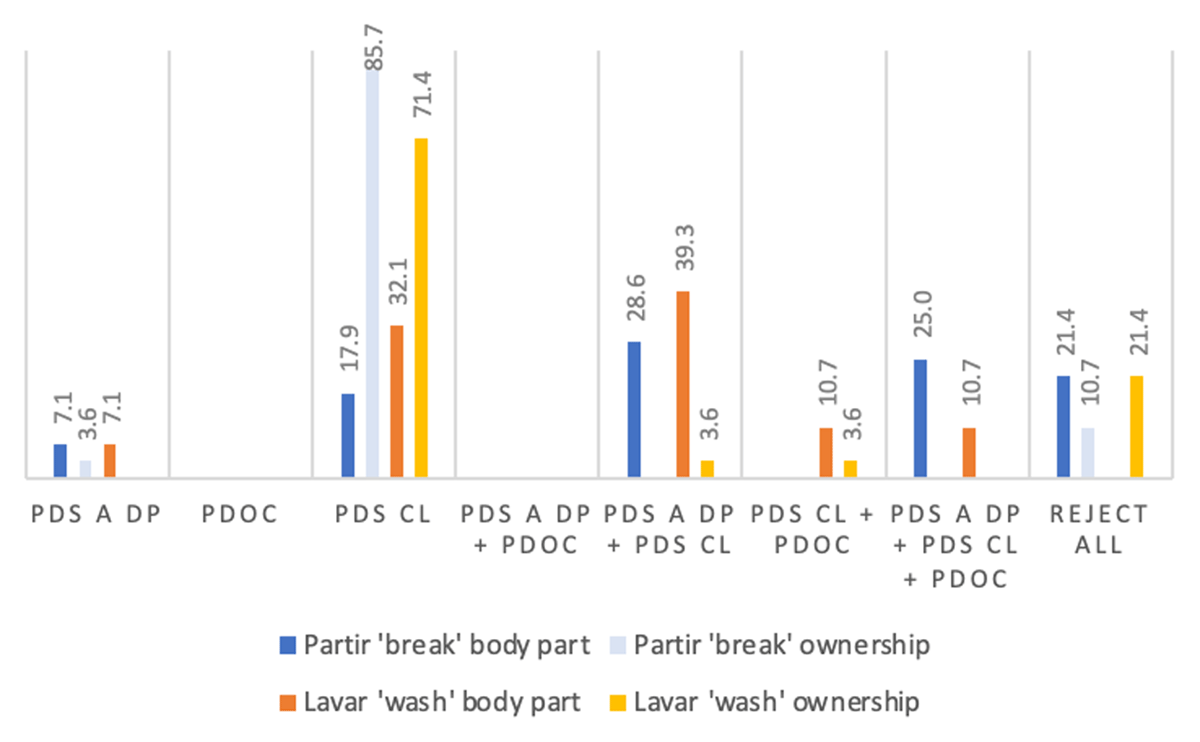

Finally, Figures 4 and 5 present the results for the third factor, that is the schooling level (SEC vs. UNIV), separating by transitive verb (partir ‘break’ vs. wash ‘lavar’) and possession relation. Again, the numbers in the figures represent the percentage of informants out of the total (N. 56) that accepted PDSs and/or PDOCs.

Informants from both groups score higher regarding the acceptance of PDSs with dative clitics when the ownership relation is at stake, irrespective of the transitive verb (60.7% for each transitive verb, for the SEC group; 85.7%, with partir ‘break’, and 71.4%, with lavar ‘wash’, for the UNIV group). This contrasts with the rate of acceptance for the same structure with a body-part relation (respectively 17.9% with partir ‘break’, and 32.1%, with lavar ‘wash’). As shown in Figure 4, informants from the SEC group prefer PDSs with both a DPs and CLs when the body-part relation is involved (42.9% and 50.0% for each verb). Instead, as Figure 5 shows, those from the UNIV group score lower on the same condition (28.6% and 39.3%, for each verb). It is also noteworthy that none of the informants from group UNIV accept either PDOCs or both PDSs with a DPs and PDOCs, irrespective of the transitive verb and the possession relation. Finally, while some informants from group UNIV accept PDSs, with both a DP and CL, and PDOCs when the body-part relation is involved (25.0% and 10.7% for each verb), informants from group SEC tend to accept the same possessor form exclusively with the transitive verb lavar ‘wash’, although with low rates, independently of the possession relation (17.9% for body-part and 10.7% for ownership).

Further data exploration was pursued, aiming to fit a logistic regression model to the informants’ data. Thus, we tested models with three independent binary variables (verb class, possession relation and schooling level) and with the possessor form as a dependent variable. As the responses with the higher percentages included a DP and/or CL, the models only considered responses with (i) a DP, alone or with any other possessor form; (ii) CL, alone or with any other possessor form. The models were based on 224 responses for each of the possessor’s form tested: 224 responses for a DP and 224 responses for CL.

Concerning the choice of a DP, the best model fit was achieved by using the possession relation (p-value = 1,474e-13) and the schooling level (p-value=0,01512) as independent variables, which were found to be statistically significant. This model has acceptable predictive power and, additionally, the coefficient of the possession variable is coherent with our knowledge of the data: it is predicted that the more ownership sentences are accepted, the less a DP possessor forms we get. This is even more relevant within the UNIV group.

Concerning the choice of CL, no acceptable model fit was achieved. The possession relation variable was found to be statistically significant. However, its model coefficient was contrary to what was expected, that is, the model predicts that ownership sentences generate lower acceptance of clitic possessor forms; this prediction is not coherent with the initial hypothesis. Since no acceptable model fit was achieved using the selected independent variables and model type, more data exploration is needed before we find a model to fit the informants’ responses.

No model was found where the verb class was significant. Thus, our hypothesis that the semantics of the verb would influence the choice of the possessor’s form could not be validated.

To sum up, although these results indicate instability in the grammar of the informants, they point toward tendencies which, on the other hand, can be traced back to the languages urban MozP has been in contact with. Thus, influence from Changana appears to be at work in the acceptance of a DP possessors in the nuclear situation of body-part (see Figure 1), and in the rejection of this possessor form in non-nuclear ownership PDSs (Figure 2), in contrast with EP, where ownership PDSs qualify as nuclear, therefore being acceptable with a DP. This suggests that the value of the [ipart] feature, which we claimed to be the source of the microvariation exhibited in Romance languages, is also responsible for the variation between MozP and EP. Indeed, the fact that informants exclude PDSs with a DP when the possession relation is one of ownership suggests that the [ipart] feature is less widespread in the MozP lexicon than in EP. This is consistent with what we know about PDOCs in Changana and in other Southern Bantu languages, where only body/whole-part relations between possessor and possessum license nuclear PDOCs. This means that contact with Changana appears to be a factor in the rejection of a DP in ownership PDSs.

Also, the acceptability levels for PDOCs, although very low and existing solely in utterances describing body-part relations, might be traced back to the influence of Changana, being observed mainly among informants from the SEC group. Otherwise, informants’ acceptance of PDOCs might be the result of by chance responses.

The low level of acceptability of PDOCs in both groups as compared with that of PDSs suggests that most informants are converging with the VP structure of EP. This result is in line with previous work on sentences with core give-type verbs in MozP, where it was shown that “the expression of dative objects in urban MOP is increasingly transitioning toward the patterns found in EP” (Gonçalves, Duarte & Hagemeijer, 2022).

Finally, schooling level seems to be at work in the lower scores of acceptability of PDOCs and both PDSs and PDOCs in the UNIV group, which indicates greater convergence with the VP structure of EP or else less responses by chance. This is not unexpected, since it has been argued in previous research that schooling is the main source of dissemination of Portuguese in Mozambique, and that competing grammars associated to different levels of schooling co-exist in the country (Chimbutane, 2018).

4. Conclusion

The empirical data presented in this article brings about new insights on the topic of possessor dative structures. Indeed, data from Changana corroborate the validity of the distinction between nuclear and non-nuclear PDOCs previously proposed for other Bantu languages. Using mainly data from EP and from MozP, we showed that this distinction is also valid for (post-colonial varieties of) Romance languages.

To account for microvariation across Romance PDSs, we proposed that nouns come from the lexicon with the value ‘yes’ or the value ‘no’ for the formal feature [ipart], which encodes a cultural difference relevant for the grammar of external possession. Unlike in EP, the exploratory data from MozP informants suggests that the value ‘yes’ for this feature is a sublabel present exclusively in body-part nouns.

We proposed a movement analysis for PDSs in EP, which accounts for their formal similarities with ditransitive structures, implementing through the formal feature [uposs:?] as a sublabel of both V and D/Q, respectively, the idea that, whereas ditransitive structures with give-type verbs express a dynamic possession relation, PDSs express a non-dynamic one.

Finally, the fact that nuclear and non-nuclear PDSs coexist in the same language jeopardizes Deal’s (2017) proposal that the variation of external possession structures across languages can be accounted for by means of a hierarchy of parameters. Instead, it argues in favour of our hypothesis that the value for the [ipart] formal feature is responsible for such coexistence.

Notes

- PDSs occur in the Germanic languages German, Dutch, and Frisian; in Romance languages such as French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian; in the Slavic languages Russian, Czech, Polish, Slovenian, and Serbo-Croatian; in the Baltic languages Latvian and Lithuanian; in Greek, Basque, Maltese, Hungarian (Szabolcsi, 1983), and Hebrew (Landau, 1999). [^]

- Namely in Haya (Hyman, 1977), Swahili (Keach & Rochemont, 1994), Kinyarwanda (Kimenyi, 1980; Massam, 1985; Davies, 1997), Chichewa (Baker, 1988; Simango, 2007), Chimwiini (Henderson, 2014), and Changana (Hagemeijer, et al. 2021). [^]

- It is well known that Portuguese and French are languages without clitic doubling in these structures, contrary to what happens in Spanish and Romanian. [^]

- See the following generalization on French, where lexical dative means a dative argument of a give-type verb: “A lexical dative can freely occur in any sentence structure since it is part of the lexical definition of the verb. A non lexical dative is only perfectly acceptable as a clitic on the verb.” (Rooryck, 1988, p. 384). [^]

- With respect to the role played by inalienability in licensing PDSs, Romanian has been considered an exception to the “standard” view of PDSs in Romance. [^]

- It should be noticed that ditransitive sentences where the primary object of the verb and the Theme argument bear a possession relation distinct from body-part are often ambiguous between a reading as a PDOC and a reading as a DOC with a Beneficiary primary object. The following example from Kinyarwanda, translated by Massam (1985, p. 254) as a PDOC, may therefore also mean ‘The boy is reading the book for the girl.’:

On the same type of ambiguity in Romance, see section 2, and in Changana, see section 3. [^]

- Umuhuûngu

- boy

- a-ra-som-er-a

- he-pres-read-appl-asp

- umukoôbwa

- girl

- igitabo.

- book

- ‘The boy is reading the girl’s book.’

- However, not every stative verb is allowed. Picallo and Rigau (1999) consider PDSs with stative verbs ungrammatical in Spanish, mentioning specifically conocer ‘be acquainted with,’ and saber ‘to know’. In EP, non-nuclear PDSs are accepted with conhecer ‘to know, to be acquainted with’, a phase stative, but not with saber ‘to know’, a non-phase stative (see Duarte & Oliveira, 2018). [^]

- See Beavers (2011), who considers verbs like ‘to see’, ‘to ear’, and ‘to smell’ non-eventive verbs. [^]

- The notation ⊆ is used to indicate a subset relation. ‘A ⊆ B’ means that ‘∀x (x∈A ⇒ x∈B)’. In simple terms, if A = rose and B = flower, it follows that “a rose is a flower”. Now, in a parthood relation, that is, in a mereological relation, if A = finger and B = hand, one cannot infer that a finger is a hand. [^]

- The derivation of PDSs selected for by unaccusative verbs is similar, except for need of the possessum DP to value its Case against the T head, as no source for Accusative exists in the sentence spine of unaccusatives. [^]

- It should be noted that some analyses of nuclear PDOCs in Bantu not only assume movement of the possessor, but also reject the presence of an applicative head (see Henderson, 2014). [^]

- Changana is a pro-drop, SVO language (Ngunga & Simbine 2012), and, with respect to the position of object markers on the verb, it is a type 1 language, a classification that goes back to Beaudoin-Lietz et al. (2004) and refers to Bantu languages where one or more object markers immediately precede the verb stem (see also Nurse, 2007, 2008). Out of the existing documentation about Changana, Chimbutane (2002), in particular, discusses several aspects of Changana that are relevant to this paper. [^]

- Changana is also spoken in South Africa, Eswatini (former Swaziland), and Zimbabwe, where it is known as Tsonga or Xitsonga. [^]

- With remove verbs in general, it should be noticed that a possible source for sentences like (43) below could in fact be a derivation where the possessor is merged as one of the internal arguments of the verb (see Baker, 1996 for the same suggestion in his analysis of polysynthetic languages). [^]

- Changana also displays internal possession structures, in which we find the word order expected in a head-first language: the NP is a constituent where the head noun (the possessum) precedes the possessor, and their relation is mediated by a genitive marker. This marker, also mentioned in literature on Bantu as a connective or associative element (e.g., van de Velde, 2020), carries a morphological class marker agreeing with the possessum, as illustrated in (i).

- (i)

- (a)

- Juwawa

- Juwawa

- a-tshov-ile

- 1SM-break-pst

- voku

- 5.arm

- l-a

- 5-GEN

- Pedru.

- Pedru

- ‘Juwawa broke Pedru’s arm.’

[^]- (b)

- Juwawa

- Juwawa

- a-tsem-ile

- 1SM-cut-pst

- mi-sisi

- 4-hair

- y-a

- 4-GEN

- Mariya.

- Mariya

- ‘Juwawa cut Mariya’s hair.’

- In Chichewa and Tswana alike, an applicative extension is needed or allowed when the possession relation is not one of body-part (see (ia) vs. (ib)), although no applicative extension occurs otherwise, as shown in (iia) vs. (iib).

- (i)

- (a)

- Fisi

- hyena

- a-na-dy-er-a

- 1-pst-eat-appl-fv

- kalulu

- hare

- nsombra.

- fish

- ‘The hyena ate the hare’s fish.’

- Chichewa, Baker (1988, p. 11)

- (b)

- *Fisi

- hiena

- a-na-dy-a

- 1-pst-eat-fv

- kalulu

- hare

- nsombra.

- fish

- (ii)

- (a)

- Ngw-ana

- 1-child

- o-tlaa-go-gat-a

- sm1-fut-om2sg-crush-fv

- letsogo.

- 5-hand

- ‘The child will crush your hand.’

[^]- (b)

- Ngw-ana

- 1-child

- o-tlaa-go-j-el- a

- sm1-fut-om2sg-eat-appl-fv

- dinawa.

- 8/10.bean

- ‘The child will eat your beans.’

- Tswana, Creissels (2006, p. 108)

Acknowledgements

The research in this paper was developed within project PALMA (Possession and location: microvariation in African varieties of Portuguese, PTDC/LLT-LIN/29552/2017), funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT). We are gratefully indebted to Tjerk Hagemeijer for his participation in an early version of this research, to project grantees Catarina Cornejo and Raquel Madureira, who carried out the elicitation task, and to Joana Costa, who helped us with the exploration of the data from the elicitation task and the application of statistical models. We are indebted to two anonymous reviewers as well as to the editors of JPL for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Authier, J.-M., & Reed, L. (1992). On the syntactic status of French affected datives. The Linguistic Review, 9(4), 295–312. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/tlir.1992.9.4.295

Baker, M. (1988). Incorporation: A Theory of Grammatical Function Changing. University of Chicago Press.

Baker, M. (1996). The Polysynthesis Parameter. Oxford University Press.

Baker, M. (1999). External Possession in Mohawk: Body Parts, Incorporation, Argument Structure. In D. L. Payne & I. Barshi (Eds.), External possession (pp. 293–323). John Benjamins Publishing Company. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.39.17bak

Bally, C. (1926). L’expression des idées de sphère personnelle et de solidarité dans les langues indo-européennes [The expression of ideas in the personal sphere and solidarity in Indo-European languages]. In F. Fankhauser & J. Jud (Eds.), Festschrift Louis Gauchat (pp. 68–78). Sauerlander.

Beaudoin–Lietz, C., Nurse, D., & Rose, S. (2004). Pronominal Object Marking in Bantu. In A. Akinlabi & O. Adesola (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th World Congress of African Linguistics. New Brunswick, 2003 (pp. 175–188). Rüdiger Köppe.

Beavers, J. (2011). On affectedness. Natural language & Linguistic Theory, 29(2), 335–370. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-011-9124-6

Boneh, N., & Nash, L. (2012). Core and non-core datives in French. In B. Fernández & R. Etxeparre (Eds.), Variation in Datives: A Microcomparative perspective (pp. 22–49). Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199937363.003.0002

Bruening, B. (2001). QR obeys superiority: Frozen scope and ACD. Linguistic Inquiry, 32, 233–273. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/00243890152001762

Chimbutane, F. (2002). Grammatical functions in Changana: Types, properties and function alternations [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Australian National University. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/151216

Chimbutane, F. (2018). Portuguese and African Languages in Mozambique. In L. A. López, P. Gonçalves & J. O. Avelar (Eds.), The Portuguese Language Continuum in Africa and Brazil (pp. 89–110). John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/ihll.20.05chi

Cinque, G., & Krapova, I. (2008). The two ‘possessor raising’ constructions of Bulgarian. University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics, 18, 65–88.

Creissels, D. (2006). Syntaxe Générale. Une introduction typologique [General syntax. A typological introduction] (Vols. 1–2). Lavoisier.

Cuervo, M. C. (2003). Datives at Large. The MIT Press.

Cuervo, M. C. (2020). Datives as Applicatives. In A. Pineda & J. Mateu (Eds.), Dative Constructions in Romance and Beyond (pp. 1–39). Berlin: Language Science Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3776531

Davies, W. D. (1997). Relational succession in Kinyarwanda possessor ascension. Lingua 101(1–2), 89–114. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(96)00037-X

Deal, R. A. (2017). External possession and possession raising. In M. Everaert & H. C. van Riemsdijk. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Syntax (2nd edition). John Wiley & Sons. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9781118358733.wbsyncom047

Demonte, V. (1995). Dative alternation in Spanish. Probus, 7, 5–30. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/prbs.1995.7.1.5

Den Dikken, M. (2006). Relators and Linkers. Cambridge. The MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5873.001.0001

Duarte, I., & Oliveira, F. (2018). External Possession in Portuguese. In A. Leal (Ed.), Verbs, movement and prepositions (pp. 75–102). CLUP/FLUP. https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/114003

Dumitrescu, D. (1990). El dativo en español y en rumano [The dative in Spanish and Romanian]. Revista Española de Linguistica, 20(2), 403–429. http://www.sel.edu.es/pdf/jul-dic-90/04%20Dumitrescu.pdf

Freeze, R. (1992). Existentials and other locatives. Language, 68(3), 553–595. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/415794

Gonçalves, P. (1991). A construção de uma gramática de português em Moçambique: aspetos da estrutura argumental dos verbos [The construction of a grammar of Portuguese in Mozambique: aspects of the argument structure of verbs] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Lisbon. http://www.repositorio.uem.mz/handle/258/348.

Gonçalves, P. (2002). The role of ambiguity in second language change: the case of Mozambican African Portuguese. Second Language Research, 18(4), 325–347. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1191/0267658302sr209oa

Gonçalves, P. (2004). Towards a unified vision of classes of language acquisition and change: arguments from the genesis of Mozambican African Portuguese. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 19(2), 225–259. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/jpcl.19.2.01gon

Gonçalves, P. (2010). A génese do português de Moçambique [The genesis of Mozambican Portuguese]. INCM.

Gonçalves, R., Duarte, I., & Hagemeijer, T. (2022). Dative microvariation in African varieties of Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 21(6), 1–39. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/jpl.8488

Guéron, J. (1985). Inalienable possession, PRO-inclusion, and lexical chains. In J. Guéron, J.-Y. Pollock & H.-G. Obenauer (Eds.), Grammatical Representation (pp. 43–86). Foris. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783112328064-004

Hagemeijer, T., Chimbutane, F., Duarte, I., & Gonçalves, R. (2021, May, 27–29). Possessor datives in contact: a case-study of African varieties of Portuguese [Conference presentation]. New Issues in Language Contact Studies (NILCS), Aquila, Italia.

Hagemeijer, T., Mendes, A., Gonçalves, R., Cornejo, C., Madureira, R., & Généreux, M. (2022). The PALMA corpora of African varieties of Portuguese. In N. Calzolari, F. Béchet, P. Blache, K. Choukri, C. Cieri, T. Declerck, S. Goggi, H. Isahara, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, H. Mazo, J. Odijk & S. Piperidis (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2022) (pp. 5047–5053) European Language Resources Association (ELRA). https://aclanthology.org/2022.lrec-1.539.pdf

Hale, K. (1986). Notes on world view and semantic categories: some Warlpiri examples. In P. Muysken & H. van Riemsdijk (Eds.), Features and Projections (pp. 233–254). Foris. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110871661-009

Henderson, B. (2014). External possession in Chimwiini. Journal of Linguistics, 50(2), 297–321. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24583305. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226714000036

Hole, D. (2005). Reconciling “possessor” datives and “beneficiary” datives – Towards a unified voice account of dative binding in German. In C. Maienborn & A. Wöllstein (Eds.), Event Arguments: Foundations and Applications (pp. 213–242). Max Niemeyer Verlag. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110913798.213

Hyman, L. (1977). The syntax of body parts in Haya. In E. R. Byarushengo, A. Duranti & L. Hyman (Eds.), Haya Grammatical Structure (pp. 99–117). University of Southern California. https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/56/docs/SCOPIL6-Haya_grammatical_structure.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). (2019). IV Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação 2017: Resultados definitivos [IV general population and housing census 2017]. Instituto Nacional de Estatística.

Kayne, R. (1975). French syntax. The MIT Press.

Keach, C. M., & Rochemont, M. (1994). On the Syntax of Possessor Raising in Swahili. Studies in African Linguistics, 23, 81–106. DOI: http://doi.org/10.32473/sal.v23i1.107418

Kempchinsky, P. (1992). Syntactic Constraints on the Expression of Possession in Spanish. Hispania, 75(3), 697–704. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/344150

Kimenyi, A. (1980). A relational grammar of Kinyarwanda. University of California Press. https://linguistics.ucla.edu/images/stories/Kimenyi.1976.pdf

Lamiroy, B. (2003). Grammaticalization and external possessor structures in Romance and Germanic languages. In M. Coene & Y. D’hulst (Eds.), From NP to DP: Volume 2: The expression of possession in noun phrases (pp. 257–280). John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/la.56.15lam

Lamiroy, B., & Delbecque, N. (1998). The possessive dative in Romance and Germanic languages. In N. Delbecque, K. Lahousse & W. van Langendonck (Eds.), Case and Grammatical Relations across Languages. The Dative (Vol. 2) (pp. 29–74). John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/cagral.3.04lam

Landau, I. (1999). Possessor raising and the structure of VP. Lingua, 107, 1–37. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3841(98)00025-4

Manzini, M. R., & Franco, L. (2016). Goal and DOM Datives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 34(1), 197–240. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43698471. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9303-y

Marantz, A. (1993). Implications of asymmetries in double object constructions. In S. Mchombo (Ed.), Theoretical Aspects of Bantu Grammar (pp. 113–150). CLSI Publications.

Massam, D. (1985). Case Theory and the Projection Principle. [Doctoral dissertation, MIT]. MIT. http://www.ai.mit.edu/projects/dm/theses/massam85.pdf

Miguel, M. (2004). O Sintagma Nominal em Português Europeu: Posições de Sujeito. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Lisbon.

Miguel, M., Gonçalves, A., & Duarte, I. (2011). Dativos não argumentais em português [Non-lexical dative arguments in Portuguese]. In A. Costa, I. Falé & P. Barbosa (Eds.), Textos seleccionados do XXVI Encontro Nacional da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística (pp. 388–400). APL/Colibri. https://apl.pt/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Miguel_Goncalves_Duarte.pdf

Ngunga, A., & Simbine, M. C. (2012). Gramática Descritiva do Changana [Descriprive grammar of Changana]. Centro de Estudos Africanos (CEA)–Universidade Eduardo Mondlane.