1 Introduction

The impersonal verb custar ‘cost’ in European Portuguese presents us with an interesting puzzle.1 At first sight, all that needs to be said about it is that its infinitival complement may be optionally preceded by the preposition a ‘to’, with a corresponding subtle difference in meaning, as illustrated in (1) below. That is, custar may select for either a prepositionless or a prepositional infinitival as a matter of lexical subcategorization.

- (1)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- escrever

- write-INF

- o

- the

- relatório.

- report

- ‘Writing the report was hard on me.’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- escrever

- write-INF

- o

- the

- relatório.

- report

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in writing the report.’

Curiously, however, a reflexive clitic in the infinitival clause co-referring with the matrix experiencer must sometimes be deleted in the prepositional version but not in its prepositionless counterpart, as exemplified by the contrast in (2).

- (2)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- sentar-*(me)

- sit-INF-CL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘To sit on the ground pained me.’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentar-(*me)

- sit-INF-CL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in sitting on the ground.’

The sentences in (3) below present additional attested examples of this unexpected availability of deletion of the reflexive clitic in the prepositional complement of custar. In each of the examples, the infinitival verb should in principle be associated with a reflexive clitic (levantar-me, adaptar-me, integrar-me and convencer-me, respectively).

- (3)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- levantar,

- raise

- pois

- because

- estava

- was

- cansado

- tired

- do

- of-the

- dia

- day

- de

- of

- ontem.

- yesterday

- ‘It was hard for me to get up because I was tired from yesterday.’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- adaptar

- adapt

- ao

- to-the

- modo

- way

- de

- of

- jogar

- play

- do

- of-the

- Barcelona.

- Barcelona

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in playing in the manner of the Barcelona team.’

- c.

- não

- not

- sei

- know

- bem

- well

- porquê,

- why

- custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- integrar

- integrate

- na

- in-the

- universidade.

- university

- ‘I don’t know why, it was hard for me to adapt to the university.’

- d.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- convencer

- persuade

- de

- of

- que

- that

- nada

- nothing

- faria

- would-do

- como

- as

- viageiro (…)

- homing-pigeon

- mas

- but

- tive

- had

- de

- of

- me

- myself

- render

- render

- à

- to-the

- evidência.

- evidence

- ‘I very much resisted to recognize that it would not be successful as homing pigeon but I eventually had to accept it.’ (Google search, 03-07-2016)

This process of reflexive deletion in European Portuguese involves a plethora of complexities. First of all, the availability of deletion is sensitive to the type of verb involved in the embedded clause. Putting aside lexical idiosyncrasies which may affect speakers’ judgements, three general patterns can be identified, as outlined in (4).2

- (4)

- ● Deletion is impossible if the reflexive clitic can alternate with a non-reflexive argument with no significant changes in the meaning of the verb:

- a.

- Custou-nos

- cost-usCL.DAT

- a

- to

- ver-*(nos)

- see-REFL1PL

- na

- in-the

- fotografia.

- picture

- ‘It was hard for us to succeed in spotting ourselves in the picture.’

- a’.

- Custou-nos

- cost-usCL.DAT

- a

- to

- vê-los

- see-themCL.ACC

- na

- in-the

- fotografia.

- picture

- ‘It was hard for us to succeed in spotting them in the picture.’

- ● Deletion is optional with verbs that always require a reflexive clitic, regardless of whether or not they are semantically reflexive (that is, verbs that are traditionally classified as intrinsically “pronominal”):

- b.

- Custou-te

- cost-youCL.DAT

- a

- to

- arrepender-(te)

- repent-REFL2SG

- de

- of

- tudo

- everything

- o

- the

- que

- what

- fizeste.

- did-2SG

- ‘It was hard for you to succeed in repenting everything you did.’

- b’.

- *Custou-te

- cost-youCL.DAT

- a

- to

- arrependê-la

- repent-herCL.ACC

- de

- of

- tudo

- everything

- o

- the

- que

- what

- fez.

- did-3SG

- *‘It was hard for you to make her repent everything she did.’

- ● Deletion is obligatory for some speakers (and possible for others) if alternation between reflexive and non-reflexive arguments leads to (slight) changes with respect to thematic properties of the arguments involved:3

- c.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- levantar-(*me)

- raise-REFL1SG

- da

- from-the

- cadeira.

- chair

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in rising from the chair.’

- c’.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- levantá-la

- raise-herCL.ACC

- da

- from-the

- cadeira.

- chair

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in raising her from the chair.’

Second, custar is, to the best of our knowledge, the only verb in European Portuguese that allows both types of impersonal constructions illustrated in (1) and correlates deletion of the reflexive clitic in (2)/(3) with the presence or absence of the preposition. However, this deletion process is not necessarily dependent on the presence of the preposition a in the embedded clause, as the contrast between (2a) and (2b) could lead one to think. This phenomenon is also found with the (prepositionless) infinitival complement of perception and causative verbs, as shown in (5).

- (5)

- a.

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- viu-te

- saw-youCL.ACC

- desequilibrar-(*te)

- lose-balance-REFL2SG

- e

- and

- não

- not

- te

- youCL.ACC

- agarrou.

- grabbed

- ‘Maria saw you lose your balance and did not grab you.’

- b.

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- sentiu-se

- felt-REFL3SG

- desequilibrar-(*se)

- lose-balance-REFL3SG

- e

- and

- caiu.

- fell

- ‘Maria felt herself lose her balance and fell.’

- c.

- O

- the

- professor

- professor

- mandou-me

- ordered-meCL.ACC

- sentar-(*me)

- sit-REFL1SG

- na

- in-the

- fila

- row

- da

- of-the

- frente.

- front

- ‘The professor ordered me to sit in the front row.’

- d.

- O

- the

- João

- João

- fez-nos

- made-usCL.ACC

- queixar-(*nos)

- complain-REFL1PL

- à

- to-the

- polícia.

- police

- ‘João made us complain to the police.’

It is worth observing that the data in (5) do instantiate biclausal bare infinitival ECM structures and should not be confused with restructuring faire-infinitive constructions, which independently exclude reflexive clitics associated with the infinitival verb (see Kayne 1975; Gonçalves 1999; among others). The preverbal vs. postverbal position of the embedded subject in (6) below, for instance, respectively signals an ECM and a faire-infinitive construction. Notice that the reflexive clitic associated with the infinitival verb is licensed in the ECM configuration in (6a), but not in the faire-infinitive counterpart in (6b).

- (6)

- a.

- {Mandei/Vi}

- ordered-1SG/saw-1SG

- o

- the

- menino

- boy

- deitar-se.

- lie-down-INF-REFL3SG

- b.

- *{Mandei/Vi}

- ordered-1SG/saw-1SG

- deitar-se

- lie-down-INF-REFL3SG

- o

- the

- menino.

- boy

- ‘I sent the boy to bed/I saw the boy go to bed.’

A confounding factor is that for some speakers (including the first author, but not e.g. Gonçalves 1999), suppressing the reflexive can save faire-infinitive sentences with causative verbs but, crucially, not with perception verbs. Thus, these speakers allow a reflexive reading for (7a) below, for instance, but not for (7b), which can only have a nonreflexive interpretation in which the infinitival subject is a null pronoun with arbitrary interpretation. This shows that the deletion of reflexives seen in (5), for example, is not the rescue strategy available for some speakers in faire-infinitive constructions such as (7a), for it involves not only causative (see (5c-d)), but also perception verbs (see (5a-b)).

- (7)

- a.

- Mandei

- ordered-1SG

- deitar

- lie-down-INF

- o

- the

- menino.

- boy

- ‘I sent the boy to bed.’ or ‘I made someone put the boy to bed.’

- b.

- Vi

- saw-1SG

- deitar

- lie-down-INF

- o

- the

- menino.

- boy

- ‘I saw someone put the boy to bed.’ but not ‘I saw the boy go to bed.’

Finally, deletion of reflexives also seems sensitive to the finiteness specifications of the clause separating the two clitics. In a sentence such as (8) below, for instance, where the clitics are separated by a finite clause, deletion is not allowed.

- (8)

- Eu

- I

- pergunto-me

- ask-REFL1SG

- se

- if

- devo

- should-1SG

- queixar-*(me)

- complain-REFL1SG

- à

- to-the

- polícia.

- police

- ‘I wonder if I should complain to the police.’

This brief survey of the complexities involving reflexive deletion in European Portuguese raises the question of what property the prepositional infinitival of custar in (1b) has that makes it bluntly contrast with (1a) regarding the phenomenon of reflexive deletion illustrated in (2b) and (3). As we have just seen, it cannot be just a matter of lexical subcategorization. Crucially, we cannot say that reflexive deletion is somehow licensed by the preposition subcategorized by custar, for it can also be licensed in the prepositionless complement of perceptual and causative verbs (see (5)). Thus, we seem to be forced to either take the preposition a and perceptual and causative verbs to form a natural class or assume a construction specific condition tied to custar a banning the co-occurrence of the relevant clitics. Needless to say, neither of these options is conceptually appealing.

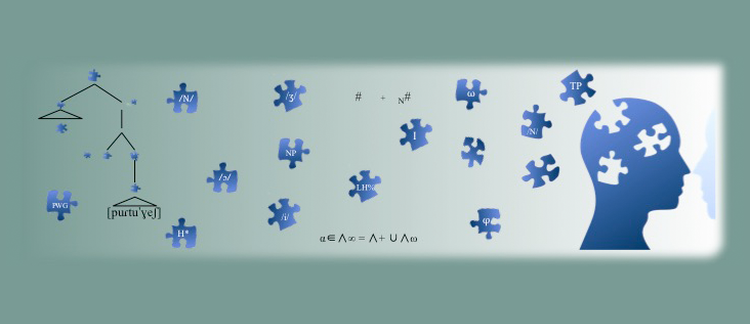

Our approach to this puzzle has two parts. Building on work by Martins and Nunes (2005), we first argue that the relevant difference between (1a) and (1b) involves obligatory control. Once this is established, we then proceed to show how the contrast between (2a) and (2b) may receive a natural account under the movement theory of control (MTC; see e.g. Hornstein 1999, 2001; Boeckx, Hornstein, and Nunes 2010). We should point out at the outset that it is not our goal to undertake a comparative evaluation of different theories of control with respect to the data presented here. Our main reason for framing the discussion in terms of the MTC is that one of its key ingredients – namely, the assumption that obligatorily controlled PRO is a deleted copy of the “controller” – provides a straightforward way to handle reflexive deletion within the prepositional complement of custar. We leave for another opportunity an adequate investigation of whether and how non-movement approaches to control can replicate the results obtained under the MTC (see Martins and Nunes forthcoming).

Before we move to the discussion proper, some clarification remarks are in order. What matters for the argument to be developed below is the existence of contrasts like (2), relative to the availability of deletion of the embedded reflexive clitic. Whether deletion may be forbidden, optional, or mandatory for different speakers is irrelevant for the ensuing discussion. What is important is that whenever deletion is possible (for a given speaker), it takes place in the prepositional, but not in the prepositionless, infinitival complement of custar. It is also worth noting that the relevant contrast only arises if the infinitival verb does not allow an intransitive use. Speakers that independently allow the verbs sentar ‘sit’ or levantar ‘to raise’, for example, to be intransitive do not identify the contrast in (2) or see anything especial about (4c), but do so in analogous sentences with verbs that disallow an intransitive option in their grammars.

The following attested examples involving the verb habituar ‘get used to’ (Google search, 03/07/2016) illustrate the relevant aspects of this variation:

- (9)

- no

- in-the

- início

- beginning

- custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- habituar-me

- get-used-INF-REFL1SG

- a

- to

- esta

- this

- realidade

- reality

- ‘(Coming from a small village to the city), it was hard for me to succeed in adapting to this new reality.’

- (10)

- No princípio

- in-the beginning

- custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- habituar, (…)

- get-used-INF

- mas

- but

- agora

- now

- já

- already

- me

- REFL1SG

- habituei

- got-used

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in accepting it (i.e. having diabetes) but now I can deal with it.’

- (11)

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- habituar

- get-used-INF

- a

- to

- esta

- this

- coisa

- thing

- de

- of

- ser

- be-INF

- só

- only

- eu.

- I

- Mas

- but

- habituei.

- got-used

- E

- and

- gosto.

- like

- ‘It was hard to get used to being alone. But I got used to it. And I enjoy it.’

- (12)

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- habituar-me

- get-used-INF-REFL1SG

- ao

- to-the

- Tom

- Tom

- mas

- but

- lá

- eventually

- me

- REFL1SG

- habituei.

- got-used

- ‘It was hard on me to get used to Tom but eventually I did.’

Speakers that allow sentences like (9) may simply not have the relevant ban on identical clitics in their grammars and deletion is not an option. Thus, (9) contrasts with (10), where the reflexive of the first conjunct has been deleted. That this indeed involves a case of reflexive deletion and not an intransitive use of habituar is shown by the fact that the reflexive clitic is present in the second conjunct of (10). Furthermore, notice that the infinitival complement in (10) is prepositional, which conforms with the generalization that deletion is only licensed when the preposition is present (see (2)). In turn, (11) apparently contradicts what we have just said, for there is no reflexive in the infinitival complement and the preposition is not present either. However, when we examine the second conjunct of (11), we see that this speaker independently treats habituar as intransitive. Hence, (11) is not at odds with (2), for the first conjunct does not involve deletion, but an intransitive use of habituar. Finally, the second conjunct of (12) shows that this other speaker takes habituar to be reflexive, but the reflexive in the first conjunct cannot be deleted because the infinitival is not prepositional. The grammar that we will be discussing throughout the paper is the one illustrated in (2), (3), and (10), that is, the grammar where deletion of reflexive clitics is enforced in the prepositional complement of custar.

The paper is organized as follows. In section 2 we make some brief remarks regarding the deletion process illustrated in (2b)/(3)/(4b’)/(4c’)/(5)/(10). It should be pointed out that our goal is not to account for the deletion process itself, but to use it as an independent criterion of empirical adequacy to test structures assigned to (1a) and (1b). In section 3 we show that the two infinitival complements in (1) sharply contrast with respect to obligatory control diagnostics and that the type of deletion seen in (2b) is limited to the obligatory control structure. Given this result, in section 4 we show that this correlation between obligatory control and deletion can receive a straightforward account if the obligatorily controlled infinitival subject is analyzed as copy of the “controller”, as postulated by the MTC. Section 5 presents some concluding remarks.

2 Some remarks on the deletion of reflexive clitics with custar a

Bearing in mind that only the prepositional complement of custar may allow for deletion (see (2a) vs. (2b)), let us consider the data in (13) and (14).

- (13)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentar-(*me)

- sit-REFL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in sitting on the ground.’

- b.

- Custou-te

- cost-youCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentar-(*te)

- sit-REFL2SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘It was hard for you to succeed in sitting on the ground.’

- (14)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentá-lo

- seat-himCL.ACC

- naquele

- on-that

- banco.

- bench

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in seating him on that bench.’

- b.

- Custou-lhe

- cost-himCL.DAT

- a

- to

- pagar-lhe

- pay-himCL.DAT

- toda

- all

- a

- the

- dívida.

- debt

- ‘It was hard for [him/her]i to succeed in paying [him/her]k all the debt.’

At first sight, the contrast between the sentences in (13), on the one hand, and (14a), on the other, simply indicates that deletion is triggered when the clitic in the embedded clause is identical to the clitic attached to custar; hence, deletion takes place in (13a) and (13b), but not in (14a). However, the contrast between the two sentences of (13) and (14b) shows that phonological identity is not sufficient, for the two clitics in (14b) are identical, but deletion is not triggered. Upon close inspection, we can see that deletion targets reflexive clitics; hence, it is possible in (13), but not in (14).4

For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that some speakers may allow deletion of reflexive se in the presence of a third person dative clitic, as illustrated in (15) and the attested example in (16).5

- (15)

- Custou-lhe

- cost-himCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentar-%(se)

- sit-REFL3SG

- naquele

- on-that

- banco.6

- bench

- ‘It was hard for him/her to succeed in sitting on that bench.’

- (16)

- Diogo

- Diogo

- também

- also

- acordou

- woke-up

- cedo

- early

- e

- and

- custou-lhe

- cost-himCL.DAT

- a

- to

- levantar!7

- raise

- ‘Diogo also woke up early and it was hard for him to get up.’

This seems to suggest that for some speakers, se and lhe are to be computed as morphologically similar enough to trigger deletion of the reflexive. As pointed out to us by Renato Lacerda (personal communication), this may be less unexpected than it looks if one takes into consideration that in Spanish, the reflexive se may be a suppletive form of the dative le in “spurious”-se constructions, as shown in (17) (see e.g. Perlmutter 1971; Bonet 1995).

- (17)

- Se/*Le

- SE/himCL.DAT.3SG

- lo

- itCL.ACC

- diste.

- gave.2SG

- (Spanish)

- ‘You gave it to him/her.’

What matters for the purposes of our discussion is that for speakers who allow deletion of se in sentences such as (15), they only permit it in the prepositional version. In the following discussion we will abstract away from the variation regarding sentences like (15), for it does not interfere with the distinction between the two types of infinitival complements associated with custar.

3 Differences between the two infinitival complements of custar

Let us now return to the intriguing puzzle in (2), repeated below in (18), and discuss differences between the two types of complement of custar that may provide a basis for us to account for why deletion is triggered in (18b) and blocked in (18a).

- (18)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- sentar-*(me)

- sit-REFL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘To sit on the ground pained me.’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentar-(*me)

- sit-REFL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in sitting on the ground.’

3.1 Some interpretive differences

Despite their similarities, the two infinitival complements of custar contrast in many aspects (see Martins and Nunes 2005). Although the experiencer argument of custar is interpreted as affected by the state of affairs described in the infinitival clause of both types of complements, in the prepositional version it is also interpreted as being more actively engaged in carrying out the events described in the infinitival. This is very clear in the pair of sentences in (19) below, where the speaker’s attitude towards the secretary goes in opposite directions depending on whether or not the infinitival is prepositional. Hence, the two structures may be pragmatically adequate with antonym verbs in the infinitival domain, as illustrated in (20). (20b), in particular, would be pragmatically odd with perder (‘lose’) instead of ganhar (‘win’).

- (19)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- despedir

- fire-INF

- a

- the

- secretária.

- secretary

- ‘I felt pity that the secretary was fired’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- despedir

- fire

- a

- the

- secretária.

- secretary

- ‘It took a lot of effort on my side for me to succeed in firing the secretary.’

- (20)

- a.

- Custou-lhes

- cost-themCL.DAT

- muito

- much

- perder

- lose-INF

- o

- the

- jogo.

- game

- ‘It was very painful for them to lose the game.’

- b.

- Custou-lhes

- cost-themCL.DAT

- muito

- much

- a

- to

- ganhar

- win

- o

- the

- jogo.

- game

- ‘It took them a lot of continued effort to succeed in winning the game.’

Also telling is the pragmatic oddness of b-sentences in (21) and (22) below, as people are not normally engaged in bringing about the kind of events described in their embedded clauses.

- (21)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- ver

- see-INF

- morrer

- die-INF

- o

- the

- cachorro.

- dog

- ‘Seeing the dog die was painful for me.’

- b.

- #Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- ver

- see-INF

- morrer

- die-INF

- o

- the

- cachorro.

- dog

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in the goal of seeing the dog die.’

- (22)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- muito

- much

- perder

- lose-INF

- o

- the

- meu

- my

- amigo.

- friend

- ‘Losing my friend was very painful for me.’

- b.

- #Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- muito

- much

- a

- to

- perder

- lose-INF

- o

- the

- meu

- my

- amigo.

- friend

- ‘It took some effort on my side in order for me to lose my friend.’

This engagement by the experiencer in the prepositional version may also correlate with duration, as illustrated by the different interpretations of (23a) and (23b) below. It is also behind the oddness of (24a) against the felicity of (24b).8

- (23)

- a.

- Todas

- all

- as

- the

- manhãs

- mornings

- me

- meCL.DAT

- custa

- costs

- acordar.

- wake-up-INF

- ‘Every morning waking up upsets me.’

- b.

- Todas

- all

- as

- the

- manhãs

- mornings

- me

- meCL.DAT

- custa

- costs

- a

- to

- acordar.

- wake-up-INF

- ‘Every morning it takes some time for me to get awake.’

- (24)

- a.

- #Por

- for

- causa

- cause

- da

- of-the

- greve

- strike

- dos

- of-the

- transportes,

- transportation

- custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- chegar

- arrive-INF

- a

- on

- horas

- time

- ao

- to-the

- trabalho.

- work

- ‘Due to the strike in public transportation, I felt bad about getting to work on time.’

- b.

- Por

- for

- causa

- cause

- da

- of-the

- greve

- strike

- dos

- of-the

- transportes,

- transportation

- custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- chegar

- arrive-INF

- a

- on

- horas

- time

- ao

- to-the

- trabalho.

- work

- ‘Due to the strike in public transportation, it took me a lot of effort and time to get to work on time.’

3.2 Some differences in structural complexity

The two infinitival complements also contrast in terms of structural complexity, as the prepositional version does not license auxiliaries (see (25)), modals (see (26)), or independent time adverbials (see (27)):

- (25)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- ter

- have-INF

- estado

- been

- em

- on

- pé

- foot

- tanto

- much

- tempo.

- time

- ‘Having been standing up for so long was painful for me.’

- b.

- *Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- ter

- have

- estado

- been

- em

- on

- pé

- foot

- tanto

- much

- tempo.

- time

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in having stood up for so long.’

- (26)

- a.

- Custa-me

- costs-meCL.DAT

- só

- only

- poder

- can-INF

- beber

- drink

- água.

- water

- ‘Being allowed to drink only water is hard for me’

- b.

- *Custa-me

- costs-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- só

- only

- poder

- can

- beber

- drink

- água.

- water

- ‘It is hard for me to succeed in being allowed to drink only water.’

- (27)

- a.

- Custa-me

- costs-meCL.DAT

- só

- only

- ter

- have-INF

- folga

- day-off

- amanhã.

- tomorrow

- ‘Being off duty only tomorrow upsets me.’

- b.

- *Custa-me

- costs-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- só

- only

- ter

- have

- folga

- day-off

- amanhã.

- tomorrow

- ‘It has been hard for me to succeed in being off duty only tomorrow.’

3.3 Standard Control diagnostics

The interpretive and structural differences reported above suggest that the prepositional infinitival but not its prepositionless counterpart may instantiate obligatory control. This is further confirmed when unequivocal diagnostics of obligatory control are examined, as we will show below.

3.3.1 Licensing of independent subjects

The two infinitivals differ in their ability to license an overt subject. The attested prepositionless example in (28a), for instance, sharply contrast with its prepositional counterpart in (28b) in allowing an overt subject (which indicates that the prepositionless sentence displays an inflected infinitive, a matter we will return to in section 3.3.5).

- (28)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- ele

- he

- levar

- take-INF

- o

- the

- exercício

- exercise

- em

- in

- branco.

- white

- ‘It upset me that he went to school without his homework assignment done.’

- (http://paranoias-de-mae.blogs.sapo.pt/2012/10/, 04/07/2016)

- b.

- *Custou-meCL.DAT

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- ele

- he

- levar

- take

- o

- the

- exercício

- exercise

- em

- in

- branco.

- white

The contrast in (28) can be accounted for if the prepositional but not the prepositionless infinitival involves obligatory control. Accordingly, only prepositionless infinitivals can license a (null) expletive, as illustrated in (29).

- (29)

- a.

- Custa-nos

- costs-usCL.DAT

- [expl

- haver

- exist-INF

- pessoas

- people

- com

- with

- fome]

- hunger

- ‘That there are hungry people pains us.’

- b.

- *Custou-nos

- cost-usCL.DAT

- a

- to

- [expl

- haver

- exist

- estudantes

- students

- preparados

- prepared

- para

- for

- o

- the

- exame]

- exam

If the prepositionless infinitival can license an independent subject within its clause, as the combination of the data in (28) and (29) clearly shows, we are led to expect that in sentences such as (30), the null subject of the prepositionless infinitival need not correfer with the matrix experiencer, whereas the null subject of the prepositional version (as an instance of obligatory control) must.

- (30)

- a.

- Custou-mei

- cost-meCL.DAT

- [eci/k

- reprovar

- fail-INF

- esse

- that

- aluno]

- student

- ‘That I/other people failed that student pained me.’

- b.

- Custou-mei

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- [eci/*k

- reprovar

- fail

- esse

- that

- aluno]

- student

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in failing that student.’/*‘It was hard for me to succeed in having other people fail that student.’

We take this prediction to be essentially correct, but it should be observed that there is a very strong bias for the embedded null subject to take the experiencer of custar as its antecedent, which leads some speakers (including one of the anonymous reviewers) to reject (30a) with index k and other analogous structures. We do not have an account of why this bias is stronger for some speakers and not others, but we would like to mention two points that support our description of the data. First, the non-correferential interpretation in out-of-the-blue sentences such as (30a) may become more salient if an appropriate pragmatic context is provided. This is illustrated in (31) below, for instance, where the context set by the question in (31A) pragmatically precludes the correferential reading for the null subject of the infinitival in (31B). Crucially, no pragmatic context is able to license the non-correferential reading with prepositioned infinitivals.9

- (31)

- A:

- O

- the

- que

- what

- achas

- think

- do

- of-the

- Mário?

- Mario

- ‘What do you think of Mario?’

- B:

- Custa-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- ter

- have-INF

- tanto

- such

- talento

- talent

- e

- and

- não

- not

- o

- it

- aproveitar.

- profit-INF

- ‘It pains me that he is so talented and does not take advantage of it.’

More importantly, the bias towards the correferential interpretation can be turned around via contrastively focused pronouns. In a subject control construction such as (32) below, for instance, the postverbal pronoun in the infinitival is interpreted as imposing a contrastive focus on the embedded subject (for relevant discussion, see e.g. Costa 2004; Barbosa 2009; Szabolcsi 2009). When a contrastively focused pronoun is added to (30), as shown in (33), the contrast now becomes crystal clear: the pronoun can impose a contrastive focus interpretation on an embedded subject linked to a discourse antecedent in the prepositionless complement of custar, but not in its prepositional counterpart.10

- (32)

- [o

- the

- João]i

- João

- quer

- wants

- [eci

- resolver

- solve-INF

- elei/*k

- he

- o

- the

- problema.

- problem

- ‘João wants to solve the problem himself.’

- (33)

- a.

- Custou-mei

- cost-meCL.DAT

- [eck

- resolver

- solve-INF

- elek

- he

- o

- the

- problema]

- problem

- ‘That he himself solved the problem pained me.’

- b.

- *Custou-mei

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- [eck

- resolver

- solve

- elek

- he

- o

- the

- problema]

- problem

3.3.2 The requirement of a local antecedent

(34a) below shows that to the extent that the null subject of the prepositionless infinitival may take an antecedent, it need not be local, whereas (34b) shows that the antecedent of the subject of the prepositional infinitival must be local. Like what we saw in section 3.3.1, the contrast becomes more salient if contrastive focus is added to the picture, as shown in (35).

- (34)

- a.

- [O

- the

- Rui]k

- Rui

- acha

- thinks

- que

- that

- mei

- me

- custou

- cost

- [eci/k

- escrever

- write-INF

- o

- the

- relatório]

- report

- ‘Rui thinks that my/his writing the report pained me.’

- b.

- [O

- the

- Rui]k

- Rui

- acha

- thinks

- que

- that

- mei

- me

- custou

- cost

- a

- to

- [eci/*k

- escrever

- write

- o

- the

- relatório]

- report

- ‘João thinks that it was hard for me to succeed in writing the report.’

- (35)

- a.

- [O

- the

- Rui]k

- Rui

- acha

- thinks

- que

- that

- mei

- me

- custou

- cost

- [eck

- escrever

- write-INF

- elek

- he

- o

- the

- relatório]

- report

- ‘Rui thinks that his writing the report (himself) pained me.’

- b.

- *[O

- the

- Rui]k

- Rui

- acha

- thinks

- que

- that

- mei

- me

- custou

- cost

- a

- to

- [eck

- escrever

- write-INF

- elek

- he

- o

- the

- relatório]

- report

3.3.3 On the c-command condition and the nature of the antecedent

The argument that the null subject in (34b)/(35b) requires a local antecedent presupposes that the dative argument of custar sits in a c-commanding position. That this holds true is shown by the Principle C effect illustrated in (36).

- (36)

- *Custou-lhei

- cost-himCL.DAT

- a

- to

- criticar

- criticize

- [o

- the

- João]i

- João

- *‘It was hard for himi to succeed in criticizing Joãoi.’

That being so, one predicts that a DP within the experiencer should not count as a proper antecedent for the null subject of a prepositional infinitival, due to lack of c-command. Unfortunately, this prediction cannot be tested because the experiencer argument of custar can be realized by a dative clitic, but not by a full DP, as illustrated in (37). We speculate that this idiosyncrasy is related to the inherent nature of the Case assigned by custar to its experiencer.

- (37)

- *Custou

- cost

- ao

- to-the

- João

- João

- a

- to

- escrever

- write

- o

- the

- relatório.

- report

- ‘It was hard for João to succeed in writing the report.’

The fact that custar assigns (inherent) dative Case to its specifier yields an additional contrast between the two infinitival complements of custar. As shown in (38) below, the indefinite clitic se is not licensed in the prepositionless infinitival. However, some speakers (including the first author) allow it with the prepositional infinitival, as illustrated by (39a) and the attested example in (39b). Interestingly, these speakers also allow constructions such as (40), where custar functions as a raising verb.

- (38)

- *Custa-se

- costs-SEIND

- acreditar

- believe-INF

- numa

- in-a

- coisa

- thing

- dessas.

- of-these

- ‘It is hard for one to believe in such a thing.’

- (39)

- a.

- Custa-se

- costs- SEIND

- a

- to

- acreditar

- believe

- numa

- in-a

- coisa

- thing

- dessas.

- of-these

- ‘It is hard for one to believe in such a thing.’

- b.

- Já

- already

- se

- SEIND

- custa

- cost

- a

- to

- encontrar

- find

- mas

- but

- aparece. (CORDIAL-SIN, MIG26)

- appears

- ‘It is difficult to find it nowadays but you can still catch it (that fish).’

- (40)

- Custei

- cost-PAST-1SG

- a

- to

- acreditar

- believe

- numa

- in-a

- coisa

- thing

- daquelas.

- of-those

- ‘It was hard for me to believe in such a thing.’

Under the standard assumption that indefinite se is intrinsically nominative, the ungrammaticality of (38) (for all speakers) and (39) for speakers who do not allow (40) is due to a feature clash, as the verb custar assigns inherent dative Case to its specifier (see section 3.3.2). For speakers who also admit a raising construction for custar, (39) is to be derived on a par with (40), with se being raised from the embedded clause directly to the subject position of the matrix clause, where nominative Case is available.11

3.3.4 Only-DP antecedents, VP-ellipsis, and de se readings

Additional confirmation for distinguishing the two infinitival complements of custar in terms of obligatory control is provided by the interpretive properties of sentences such as the ones in (41)-(43) below. The null subject of the prepositionless infinitival allows coreferential and bound readings when anteceded by an only-DP (see (41a)), permits strict and sloppy readings under ellipsis (see (42a)), and is compatible with a non-de se reading in contexts of lack of self-awareness (see (43a)). By contrast, the null subject of the prepositional infinitival displays the opposite behavior: it enforces a bound reading when anteceded by an only-DP (see (41b)), triggers a sloppy interpretation under ellipsis (see (42b)), and only allows de se readings, thus being pragmatically infelicitous in the context provided in (43) (see (43b)).

- (41)

- a.

- [Só

- only

- a[o

- to-the

- capitão]k]i

- captain

- lhe

- him

- custou

- cost

- [eci/k

- abandonar

- abandon-INF

- o

- the

- navio]

- ship

- ‘The captain’s abandoning the ship pained no one else other than him.’ (coreferential reading) or ‘[The captain]i regretted hisi leaving the ship, but nobody else regretted leaving the ship.’ (bound reading)

- b.

- [Só

- only

- a[o

- to-the

- capitão]k]i

- captain

- lhe

- him

- custou

- cost

- a

- to

- [eci/*k

- abandonar

- abandon

- o

- the

- navio]

- ship

- ‘The captain had problems to leave the ship, but nobody else did.’ (bound reading only)

- (42)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- [ec

- dar

- give-INF

- a

- the

- notícia]

- news

- e

- and

- ao

- to-the

- João

- João

- custou-lhe

- cost-him

- também.

- too

- ‘It pained both me and João that I had to deliver the news.’ (strict reading) or ‘It pained me that I had to deliver the news and it also pained João that he had to deliver the news.’ (sloppy reading).

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- [ec

- dar

- give

- a

- the

- notícia]

- news

- e

- and

- ao

- to-the

- João

- João

- custou-lhe

- cost-him

- também

- too

- ‘I was hard for me to succeed in delivering the news and it was hard for João to succeed in delivering the news, too.’ (sloppy reading only)

- (43)

- Context: An amnesiac soldier sees a documentary in which he is the protagonist, but he doesn’t remember that he himself is the protagonist

- a.

- Custou-lhe

- cost-him

- [ec

- depor

- lay-down-INF

- as

- the

- armas]

- weapons

- ‘It pained him that the protagonist laid down his weapons.’

- b.

- #Custou-lhe

- cost-him

- a

- to

- [ec

- depor

- lay-down-INF

- as

- the

- armas]

- weapons

- ‘It was hard for him to succeed in laying down his weapons.’

3.3.5 Differences regarding inflection

Finally, the two infinitival complements also contrast in terms of inflection. The prepositionless infinitival allows subject agreement morphology, but not the prepositional one:

- (44)

- a.

- Custou-nos

- cost-usCL.DAT

- [ec

- reprovar(mos)

- fail-INF-1PL

- aquele

- that

- aluno]

- student

- ‘That we failed that student pained us.’

- b.

- Custou-nos

- cost-usCL.DAT

- a

- to

- [ec

- reprovar(*mos)

- fail-INF-1PL

- aquele

- that

- aluno]

- student

- ‘It was hard for us to succeed in failing that student.’

The availability of agreement morphology in (44a) is actually not surprising, for the prepositionless infinitival can license an independent subject, as discussed in section 3.3.1. As for (44b), there was not an a priori expectation, for in European Portuguese subject control verbs generally do not license overt agreement morphology, whereas object control optionally do so, as illustrated in (45). In this regard, what (44b) shows is that it patterns like subject rather than object control.

- (45)

- a.

- Nós

- we

- tentamos

- tried-1PL

- contratar(*mos)

- hire-INF-1PL

- o

- the

- Pedro.

- Pedro

- ‘We tried to hire Pedro.’

- b.

- O

- the

- João

- João

- convenceu-nos

- convinced-us

- a

- to

- contratar(mos)

- hire-INF-1PL

- o

- the

- Pedro.

- Pedro

- ‘João convinced us to hire Pedro.’

There is actually interesting indirect evidence that shows that it is not the case that the prepositional infinitival in (44b) has ф-features that do not get morphologically realized, but rather that it simply has no ф-features. The evidence is based on Raposo’s (1987) observation that only uninflected infinitives license tough-movement, as shown in (46).

- (46)

- Esses

- these

- livros

- books

- são

- are

- difíceis

- hard

- de

- of

- ler(*mos)

- read-INF-1PL

- ‘These books are hard to read.’

Interestingly, only the prepositional complement of custar allows a tough-like construction, as illustrated in (47) and (48).12 If the two infinitivals were featurally identical, one should in principle expect both of them to allow tough-movement in (47) and (48). The fact that this is not what happens may be taken to show that the prepositionless infinitival has ф-features, which may be morphologically realized or not, whereas the prepositional infinitival has no ф-features whatsoever.

- (47)

- a.

- *Aqueles

- those

- alunos

- students

- custaram

- cost-PAST-3PL

- reprovar.

- fail-INF

- b.

- Aqueles

- those

- alunos

- students

- custaram

- cost-PAST-3PL

- a

- to

- reprovar.

- fail

- ‘Those students were hard to fail.’

- (48)

- a.

- *Estas

- these

- caixas

- boxes

- custam

- cost-PAST-3PL

- imenso

- immense

- carregar.

- carry-INF

- b.

- Estas

- these

- caixas

- boxes

- custam

- cost-PAST-3PL

- imenso

- immense

- a

- to

- carregar.

- carry

- ‘These boxes are very hard to carry.’

3.4 Summary

In sum, the prepositional infinitival complement of custar involves obligatory control, whereas its prepositionless infinitival complement does not, as sketched in (49).

- (49)

- a.

- [… [CL.DAT [custar [pro V-INF… ]]]]

- b.

- [… [CL.DATi [custar [PROi a V-INF …]]]

(49a) involves a personal infinitive which may license a pro in the subject position; pro may – but need not – be bound by the experiencer argument in the specifier of the VP headed by custar (see section 3.3.1). By contrast, the embedded subject of (49b), as an instance of obligatorily controlled PRO, must be bound by the experiencer argument of custar, as it is the most local c-commanding antecedent.

Having characterized the infinitival complements of custar, we may now go back to the puzzle of why prepositional infinitivals may trigger the deletion of a reflexive clitic.

4 Back to the deletion puzzle

Once the fundamental control difference between the two types of infinitival complements selected by custar has been identified in section 3, the data in (2), repeated below in (50), can be taken to show that deletion of reflexives locally bound by an (identical) clitic (see section 2) is only operative within the obligatory control structure (i.e. the prepositional infinitival complement).

- (50)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- sentar-*(me)

- sit-INF-REFL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘To sit on the ground pained me.’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentar-(*me)

- sit-INF-REFL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in sitting on the ground.’

This conclusion is confirmed by standard object control constructions (with a transitive control verb and an accusative Case marked controller) such as (51) and the attested examples in (52) (CETEM-Público, 04/07/2016), which show that deletion of the reflexive is also possible if the controller is an (identical) clitic (see section 2).

- (51)

- a.

- Eles

- they

- obrigaram-nos

- forced-us

- a

- to

- afastar-(*nos)

- get-away-REFL1PL

- daquele

- from-that

- caminho.

- path

- ‘They forced us to get away from that path.’

- b.

- O

- the

- médico

- doctor

- vai

- goes

- forçar-te

- force-you

- a

- to

- sentar-(*te)

- sit-REFL2SG

- de

- of

- outra

- other

- maneira.

- manner

- ‘The doctor will force you to sit in another way.’

- (52)

- a.

- Uma

- a

- bala

- bullet

- passou

- passed

- rasante

- low

- sobre

- over

- a

- the

- minha

- my

- cabeça (…)

- head

- obrigando-me

- forcing-me

- a

- to

- deitar

- lie

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- floor

- ‘A bullet passed low over my head, forcing-me to lie on the floor.’

- b.

- Com

- with

- um

- a

- sorriso,

- smile

- convidaram-nos

- invited-3PL-us

- a

- to

- sentar.

- sit

- ‘With a smile, they invited us to take a seat.’

- c.

- Após

- after

- ter

- have-INF

- caído

- fallen

- de

- on

- costas

- back

- num

- in-a

- pântano,

- swamp

- apressou-se

- hastened-REFL3SG

- a

- to

- levantar

- raise

- e

- and

- a

- to

- pedir

- ask

- desculpas

- apologies

- ao

- to-the

- instrutor

- instructor

- pelo

- for-the

- erro.

- mistake

- ‘After falling on his back in a swamp, he hastened to get back to his feet and apologize to the instructor for the mistake.’

It is worth noting another parallel. Recall that standard object control in European Portuguese allows the infinitival to optionally carry overt agreement morphology, whereas the prepositional complement of custar bans such inflection (see section 3.3.5). Interestingly, only the non-agreeing version licenses deletion of reflexive clitics, as illustrated by the contrast between the uninflected infinitives of (51) and their inflected counterparts in (53).

- (53)

- a.

- Eles

- they

- obrigaram-nos

- forced-us

- a

- to

- afastarmo-*(nos)

- get-away-1PL-REFL1PL

- daquele

- from-that

- caminho.

- path

- ‘They forced us to get away from that path.’

- b.

- O

- the

- médico

- doctor

- vai

- goes

- forçar-te

- force-you

- a

- to

- sentares-*(te)

- sit-2SG-REFL2SG

- de

- of

- outra

- other

- maneira.

- manner

- ‘The doctor will force you to sit in another way.’

However, deletion of reflexives when bound by an (identical) local clitic is not restricted to object control configurations. Recall that this phenomenon is also found with the infinitival complement of perception and causative verbs (see section 1), as illustrated in (54) (= (5)).

- (54)

- a.

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- viu-te

- saw-you

- desequilibrar-(*te)

- lose-balance-REFL2SG

- e

- and

- não

- not

- te

- you

- agarrou.

- grabbed

- ‘Maria saw you lose your balance and did not grab you.’

- b.

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- sentiu-se

- felt-REFL3SG

- desequilibrar-(*se)

- lose-balance-REFL3SG

- e

- and

- caiu.

- fell

- ‘Maria felt herself lose her balance and fell.’

- c.

- O

- the

- professor

- professor

- mandou-me

- ordered-me

- sentar-(*me)

- sit-REFL1SG

- na

- in-the

- fila

- row

- da

- of-the

- frente

- front

- ‘The professor ordered me to sit in the front row.’

- d.

- O

- the

- João

- João

- fez-nos

- made-us

- queixar-(*nos)

- complain-REFL1PL

- à

- to-the

- polícia.

- police

- ‘João made us complain to the police.’

The contrast between sentences such as the ones in (54), where deletion is available, and (55) below (= (8)), where deletion is blocked, suggests that the co-occurrence restriction that triggers reflexive deletion is clause bound. Hence, the two clitics in (55) do not interact with each other because they belong to different clauses.

- (55)

- Eu

- I

- pergunto-me

- ask-REFL1SG

- se

- if

- devo

- should-1SG

- queixar-*(me)

- complain-REFL1SG

- à

- to-the

- polícia.

- police

- ‘I wonder if I should complain to-the police.’

Importantly, what matters is not exactly where the higher clitic ends up, but where it is generated. In (54) the upper clitic is generated in the embedded clause and later cliticizes to the matrix verb (see e.g. Gonçalves 1999; Martins 2000), as becomes clearer with sentences such as (56) below, which involves proclisis to the matrix verb. To put it in different terms, the higher clitic of (54) and (56) has a chance to interact with the reflexive, triggering the deletion of the latter, before it moves to the matrix clause. In (55), on the other hand, there is no derivational step where the two clitics appear in the same clausal domain.

- (56)

- A

- the

- Maria

- Maria

- não

- not

- me

- me

- viu

- saw

- desequilibrar-(*me).

- lose-balance-REFL1SG

- ‘Maria didn’t see me lose my balance.’

Bearing these observations in mind, let us examine the (simplified) structures associated with (50), as respectively sketched in (57).

- (57)

- a.

- [proexpl custou-me [pro sentar-me no chão]]

- b.

- [proexpl custou-mei [PROi a sentar-me no chão]]

As discussed in section 3, the empty category in the embedded subject position is pro in the case of the prepositionless infinitival complement of custar (see (57a)), but an obligatorily controlled PRO in the prepositional version (see (57b)). However, this difference does not seem to be of much help. Given that deletion of the reflexive is triggered in (57b), but blocked in (57a), one would like to treat (57a) on a par with (55), which also blocks deletion, and (57b) with (54) and (56), which trigger deletion. In this sense, (57a) and (55) may be taken to form a natural class in the sense that its clitics are generated and surface in different clauses. Hence, it may be expected that they do not interact – a correct result. However, (57b) and (54)/(56) do not seem to form a natural class, for the higher clitic is generated in the embedded clause in the latter, but in the higher clause in the representation in (57b). In other words, if the co-occurrence restriction under discussion is indeed clause bound, the representation in (57b) leads to the incorrect prediction that the two clitics do not interact and the reflexive cannot be deleted.

The intriguing contrast between (57a) and (57b) ceases to be puzzling, though, if the obligatorily controlled PRO in (57b) is actually a deleted copy of the “controller”, as postulated by the MTC (see e.g. Hornstein 1999, 2001; Boeckx, Hornstein and Nunes 2010). We have seen that custar assigns inherent dative Case to its specifier (see section 3.3.3) and selects for either a personal or an impersonal infinitival complement (see section 3.3.5). If the embedded infinitival is personal, it assigns nominative to its Spec, regardless of whether or not its ф-features are morphologically realized, i.e., whether or not it is inflected (see section 3.3.5). The embedded subject then gets frozen in the embedded clause and custar must assign its other θ-role to a new element selected from the numeration. By contrast, if the infinitival is impersonal, it does not assign Case to its subject. Under the MTC, the subject may then move to [Spec, custar], where it gets an additional θ-role and is assigned inherent dative Case. Thus, the MTC analyzes the sentences in (50) along the lines of (58), where the embedded subject position of (50b) involves a copy of the “controller” in the embedded subject position.

- (58)

- Representations of (50) under the MTC:

- a.

- [proexpl custou-me [pro sentar-me no chão]]

- b.

- [proexpl custou-mei [mei a sentar-me no chão]]

In (58b) – but not in (58a) – there are two instances of the same clitic within the embedded clause. However, this is usually not tolerated in European Portuguese, as seen with ECM constructions in (54)/(56). Given that the ungrammaticality of the two clitics in (50b) parallels that of the sentences in (54)/(56), the exceptional deletion of the reflexive clitic in (50b) can be viewed as a way to comply with the superficial filter ruling out morphologically identical clitics within the same clause (see (58b)). As for (50a), no problem arises as the subject of the infinitival (pro) is not a clitic (see (58a)); hence, it is morphologically distinct from the reflexive clitic and no deletion is triggered. To sum up, the major assumption of the MTC – namely, that obligatorily controlled PRO is a (deleted) copy of its antecedent – provides a straightforward account of why reflexive deletion within the infinitival complement of custar can only take place if custar is used as an obligatory control verb.13

5 Concluding remarks

The MTC has all the ingredients to provide an account for the curious problem brought up by (59) (= (2)), which shows that reflexive clitics may be deleted in the infinitival complement of custar when it is used as an obligatory control verb.

- (59)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- sentar-*(me)

- sit-INF-REFL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘To sit on the ground pained me.’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- sentar-(*me)

- sit-INF-REFL1SG

- no

- on-the

- chão.

- ground

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in sitting on the ground.’

Under the MTC, we expect obligatorily controlled PRO to behave like a regular copy of its antecedent. More precisely, we expect obligatorily controlled PRO to be subject to whatever computations and restrictions apply to its antecedent in the post-syntactic components of grammar. We have seen that the co-occurrence restriction under discussion computes obligatorily controlled PRO but not a co-referential pro. From the perspective of the MTC, this is not at all surprising. If PRO is a copy of its antecedent (in this particular case, a copy of the experiencer clitic associated with custar), it may be computed with respect to the ban on morphologically identical clitics in a local domain and trigger reflexive deletion.

The discussion above has focused on the apparently erratic behavior of a single lexical item in European Poruguese (custar), but should also be considered under a broader (even if speculative) perspective. It is very likely that the lexical idiosyncrasy of custar regarding the optionality of the preposition in its infinitival complement illustrated in (1), repeated here in (60), is something that can be acquired based on primary linguistic data. That is, a child exposed to data parallel to (60a) and (60b) may reach the reasonable conclusion that the optionality in (60) is a matter of lexical subcategorization: custar may select for either a prepositionless or a prepositional infinitival.

- (60)

- a.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- escrever

- write-INF

- o

- the

- relatório.

- report

- ‘Writing the report was hard on me.’

- b.

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- a

- to

- escrever

- write

- o

- the

- relatório.

- report

- ‘It was hard for me to succeed in writing the report.’

However, all the complexities associated with reflexive deletion discussed in the preceding sections make it clear that it is very implausible to assume that a child could attain all the intricacies involving the contrast between (59a) and (59b) by relying solely on primary linguistic data. In other words, the differences between the two types of infinitival complements of custar discussed in this paper present an interesting poverty-of-stimulus puzzle and we have the ingredients to outline an innatist answer if control involves movement to thematic positions, as advocated by the MTC.

The steps towards such an answer go like this. In the process of language acquisition, a child must identify the inventory of lexical items of the target language that allow for obligatory control. In the case under discussion, a child acquiring European Portuguese must identify that (60b) involves obligatory control. Once this is attained, a child equipped with the MTC will assign the structure in (61) below to the sentence in (59b). In other words, the child will know – even in absence of positive evidence – that the experiencer of the matrix clause may be computed with respect to the co-occurrence restriction involving the embedded reflexive in (59b), thanks to its copy in the subject of the embedded clause. This predicts, for instance, that children should not master the contrast between (59a) and (59b) before establishing that structures such as (60b) involve obligatory control.

- (61)

- [proexpl custou-mei [mei a sentar-me no chão]]

Whether these speculative remarks can be adequately fleshed out or the predictions they make are on the right track is a matter that requires an independent detailed investigation, going beyond the scope of this paper.

Notes

- Throughout the paper, judgments are due to the first author, except when indicated otherwise. The patterns to be discussed here do not exist in Brazilian Portuguese, which only has the raising version of custar (see the example in (40) below and Martins and Nunes 2005 for relevant discussion). [^]

- In the following discussion we will abstract away from these independent lexical restrictions, for they do not interfere with the distinction between the two types of infinitival complements associated with custar. That is, lexical conditioning may derive the pattern in (4) for the prepositional complement, but deletion is uniformly ruled out in the case of the prepositionless complement, regardless of the lexical items involved. For concreteness, we will henceforth focus on examples of the type described in (4c). For relevant discussion and further refinements on types of reflexive verbs, see e.g. Burzio (1986); Cinque (1988); Vilela (1992); Brito, Duarte and Matos (2003); Duarte (2013); Gonçalves and Raposo (2013); Mendikoetxea (1999); Peregrín Otero (1999); Sánchez López (2002). [^]

-

For instance, reflexive structures with verbs of this class differ from reflexive structures with

standard transitive verbs like see in being incompatible with passives and

disallowing reflexive clitic doubling, as respectively shown in (i) and (ii). Note that, in (i), a

implies a’ but b does not imply b’.

- (i)

- a.

- Ele

- he

- viu-se

- saw-REFL3SG

- no

- in-the

- espelho.

- mirror

- ‘He saw himself at the mirror.’

- a’

- Ele

- he

- foi

- was

- visto

- seen

- no

- in-the

- espelho.

- mirror

- ‘He was seen at the mirror.’

- b.

- Ele

- he

- levantou-se

- raised-REFL3SG

- do

- from-the

- chão.

- floor

- ‘He rose from the floor.’

- b’

- #Ele

- he

- foi

- was

- levantado

- raised

- do

- from-the

- chão.

- floor

- ‘He was raised from the floor.’

- (ii)

- a.

- Ele

- he

- viu-se

- saw-REFL3SG

- a

- to

- si

- REFL3SG

- próprio

- own

- no

- in-the

- espelho.

- mirror

- ‘He saw himself at the mirror.’

[^]- b.

- *?Ele

- he

- sentou-se

- sat-REFL3SG

- a

- to

- si

- REFL3SG

- próprio

- own

- na

- in-the

- cadeira.

- chair

- ‘He sat at the chair.’

-

As observed by a reviewer, the two clitics in sentences like (13a), for example, are not clearly

identical from a morphological point of view, for the higher clitic is a pronoun with dative Case,

whereas the lower clitic is a reflexive with accusative Case. The point is well taken, but it is

worth observing that in Portuguese, first and second person clitics have syncretic forms for datives

and accusatives, as well as for pronouns and reflexives, as respectively illustrated below. For

concreteness, we will assume that such syncretism obliterates the relevant differences between these

clitics, rendering them identical. Whatever the ultimate specification of identity turns out to be,

the relevant point for our concerns is that it affects only the prepositional infinitival complement

of custar.

- (i)

- a.

- Ele

- he

- deu-me

- gave-meDAT

- um

- a

- presente.

- gift

- ‘He gave me a gift.’

- b.

- Ele

- he

- viu-me.

- saw-meACC

- ‘He saw me.’

- (ii)

- a.

- Ele

- he

- barbeou-me

- shaved-mePRON

- ontem.

- yesterday

- ‘He shaved me yesterday.’

[^]- b.

- Eu

- I

- barbeei-me

- shaved-meREFL

- ontem.

- yesterday

- ‘He shaved me yesterday.’

-

That deletion of the reflexive is not an option for all speakers is shown by the attested example

in (i) below, to be contrasted with (16).

[^]

- (i)

- Acordou

- woke-up

- encharcado

- drenched

- em

- in

- suor

- sweat

- e

- and

- custou-lhe

- cost-himCL.DAT

- a

- to

- levantar-se.

- raise-REFL3SG

- ‘He woke up drenched in sweat and it was hard to get up.’

- (Google search, 02-08-2016; http://dissejuno.blogspot.pt/)

- In (15) we are reporting judgements by speakers who accept deletion of reflexive se and do not have an intransitive use of sentar. The first author does not accept deletion of se in the presence of a third person dative clitic. [^]

- Example taken from: Fernando Oliveira, A Menina do Rio, Published June 20th 2016 by Books on Demand, p. 8. In this novel one finds the standard, non-intransitive use of the verb levantar. [^]

- For the ambiguity of the preposition a between a true preposition and an aspectual marker, see Gonçalves (1992, 1996); Duarte (1993); Gonçalves and Freitas (1996); Barbosa and Cochofel (2005); among others. [^]

-

Further relevant examples are given in (i) and (ii) below, whose prepositional counterparts would

be fully ungrammatical.

- (i)

- Quanto

- as

- a

- to

- esse

- that

- miúdo,

- kid

- custa-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- ter

- have-INF

- tanto

- such

- talento

- talent

- e

- and

- não

- not

- o

- it

- aproveitar.

- profit-INF

- ‘As for that kid, it pains me that he is so talented and does not take advantage of it.’

- (ii)

- A:

- —

- Porque

- why

- é

- is

- que

- that

- está

- is

- tão

- so

- aborrecido

- upset

- comigo?

- with-me

- Ainda

- still

- é

- is

- por

- for

- causa

- cause

- daquele

- of-that

- aluno?

- student

- ‘Why are you so upset with me? Is it still about that student?’

[^]- B:

- —

- É.

- is

- Custou-me

- cost-meCL.DAT

- ter

- have-INF

- reprovado

- failed

- um

- a

- aluno

- student

- que

- that

- sabe

- know

- bem

- well

- que

- that

- não

- not

- merecia.

- deserved

- ‘Yes, it is. It pained me that you failed a student that you know well didn’t deserve it.’

-

Note that (32) displays obligatory control. Thus, in contrast to (33), there is no disjoint

reference interpretation available for the subjects even if the embedded subject is focused, as

shown in (i) below. Importantly, (32) also demonstrates that when the infinitival subject is

focused, an overt subject is compatible with the simple infinitive in control structures.

[^]

- (i)

- *[o

- the

- João]i

- João

- quer

- wants

- eck

- resolver

- solve-INF

- euk

- I

- o

- the

- problema.

- problem

- ‘João wants me to solve the problem.’

-

(i) below provides attested examples of raising constructions with custar in

European Portuguese.

- (i)

- a.

- custei

- cost-1SG

- a

- to

- libertar-me,

- free-REFL1SG

- tinha

- had-1SG

- uma

- a

- dependência

- dependency

- daquele

- of-that

- homem.

- man

- ‘It was hard to free myself, as I was totally dependent on that man.’

- (http://anossavida.pt/forum/viol-ncia-dom-stica, 04/07/2016)

[^]- b.

- Espero

- hope-1SG

- sinceramente

- sincerely

- que

- that

- as

- the

- duas

- two

- últimas

- last

- épocas

- seasons

- sejam

- are-SUBJ

- apenas

- just

- um

- a

- pesadelo

- nightmare

- do

- of-the

- qual

- which

- custámos

- cost-PAST-1PL

- a

- to

- acordar.

- wake-up

- ‘I sincerely hope that the last two (football) seasons were just a nightmare from which it was hard for us to wake up.’

- (http://www.forumscp.com/index.php?topic=31904.375;wap2; 04/07/2016)

-

Attested examples are provided in (i) below.

- (i)

- a.

- A

- at

- grande

- high

- altitude

- altitude

- tudo

- everything

- é

- is

- mais

- more

- penoso (…)

- painful

- as

- the

- botas

- boots

- custam

- cost-3PL

- a

- to

- levantar

- raise-INF

- do

- of-the

- chão.

- floor

- ‘At high altitude everything is more painful. It is difficult to get your boots off the ground.’

- (CETEM-Público, 03/07/2016)

[^]- b.

- Um

- a

- momento

- moment

- mágico

- magical

- que

- that

- levou

- took

- à

- to

- loucura

- craziness

- os

- the

- gregos,

- Greeks

- orgulhosos

- proud

- de,

- of

- finalmente,

- finally

- verem

- see-3PL

- começar

- start-INF

- os

- the

- Jogos

- Games

- Olímpicos

- Olympic

- que

- that

- tanto

- so-much

- custaram

- cost-PAST-3PL

- a

- to

- organizar. (Jornal de Notícias, 13/08/2004)

- organize

- ‘A magical moment that led the Greeks to ecstasy, as they were proud to see the Olympic Games, which were so hard to organize, finally begin.’

- (Jornal de Notícias, 13-08-2004. http://www.jn.pt/arquivo/2004/interior/contar-alegorias-no-espirito-olimpico-455554.html?id=4555; 04/07/2016)

-

A reviewer asks whether one could not get the same results under a PRO-based account by assuming

that ECM and controlled infinitivals are not phases. From this perspective, a phase intervenes

between the matrix experiencer and the reflexive in (ia), but not in (ib). Thus, deletion could be

triggered in (ib) but blocked in (ia).

- (i)

- a.

- [proexpl custou-me [phase pro sentar-me no chão]]

The reviewer’s point is well taken. In fact, in Martins and Nunes (forthcoming) we assume the phase-based framework and make a detailed comparison between non-movement approaches to control and the MTC with respect to two types of co-occurrence restrictions in European Portuguese: the one discussed here, which leads to deletion of reflexives, and ungrammatical cases of indefinite se co-occurring with reflexive se. Our conclusion is that when reflexive deletion is considered in isolation, there is no clear basis for distinguishing between movement and non-movement approaches to control under a phase-based analysis. However, when reflexive deletion is computed together with the co-occurrence restriction involving indefinite and reflexive se, only the movement approach is able to provide a unified account of the two phenomena. For our current purposes, it is worth noting that our main point here – namely, to show that the different behavior displayed by each of the infinitival complements of custar with respect to reflexive deletion is linked to obligatory control and cannot be a simple matter of lexical subcategorization – still remains valid if we frame our MTC account in terms of the phase approach suggested by the reviewer. [^]- b.

- [proexpl custou-me [PRO a sentar-me no chão]]

Acknowledgements

An early version of this paper has been presented at the University of the Basque Country. We are thankful to its audience, as well as Renato Lacerda, three anonymous reviewers, and Ana Lúcia Santos (as JPL’s associate editor) for helpful comments and suggestions. Writing of the current version has been partially supported by FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (funding UID/LIN/00214/2013; first author) and CNPq (grant 307730/2015-8; second author), to which we are also thankful.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

P. Barbosa, (2009). A Case for an Agree-based Theory of Control. 11th Seoul International Conference on Generative Grammar Proceedings. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/000911 (Last accessed 03–08–2016).

P. Barbosa, F. Cochofel, (2005). A construção de infinitivo preposicionado em PE In: I. Duarte, I. Leiria, Actas do XX Encontro Nacional da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística. Lisboa: Associação Portuguesa de Linguística, pp. 387.

C. Boeckx, N. Hornstein, J. Nunes, (2010). Control as Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511761997

E. Bonet, (1995). Feature structure of Romance clitics. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13 (4) : 607. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00992853 Available at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00992853; https://www.jstor.org/stable/4047818?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

A. M. Brito, I. Duarte, G. Matos, (2003). Tipologia e distribuição das expressões nominais In: M. H. Mira Mateus, Gramática da Língua Portuguesa. Lisboa: Caminho, pp. 795.

L. Burzio, (1986). Italian Syntax: A Government-Binding Approach. Dordrecht: Reidel, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4522-7

CETEMPúblico (). CETEMPúblico: Corpus de Extractos de Textos Eletrónicos MCT/Público, Available at http://www.linguateca.pt/cetempublico/ (Last accessed 03-08-2016).

G. Cinque, (1988). On Si Constructions and the Theory of ARB. Linguistic Inquiry 19 (4) : 521. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178596.

CORDIAL-SIN (). A. M. Martins, (coord.) CORDIAL-SIN: Syntax-oriented Corpus of Portuguese Dialects (CLUL/FCT), Available at http://www.clul.ul.pt/en/research-teams/411-cordial-corpus (Last accessed 03-08-2016).

J. Costa, (2004). A. Castro, M. Ferreira, V. Hacquard, A. P. Salanova, Subjects in Spec,vP: Locality and Agree. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 47: Collected Papers on Romance Syntax, : 41.

I. Duarte, (1993). Complementos infinitivos preposicionados e outras construções temporalmente defetivas In: Actas do VIII Encontro Nacional da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística. Lisboa: Associação Portuguesa de Linguística/Colibri, pp. 145.

I. Duarte, (2013). Construções ativas, passivas, incoativas e médias In: E. B. Paiva Raposo, (Org.) Gramática do Português. Lisboa: Gulbenkian, pp. 429.

A. Gonçalves, (1992). Para uma sintaxe dos verbos auxiliares em Português Europeu. Unpublished thesis (MA). Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa.

A. Gonçalves, (1996). Aspectos da sintaxe dos verbos auxiliares do Português Europeu In: A. Gonçalves, M. Colaço, M. Miguel, T. Telmo Móia, Quatro Estudos em Sintaxe do Português: Uma abordagem segundo a Teoria de Princípios e Parâmteros. Lisboa: Colibri, pp. 7.