1. Introduction

Unlike most Romance languages described in the literature, Brazilian Portuguese is characterized by allowing not only bare plural count nouns (henceforth bare plurals), but also bare singular count nouns (henceforth bare singulars), in argument position (subject and object positions), as originally observed by Schmitt (1996: 234):

- (1)

- a.

- Crianças

- criança-s

- child-PL

- comem

- com-em

- eat-PRS.3PL

- balas

- bala-s

- candy-PL

- ‘Children eat candies’

- b.

- Criança

- criança

- child

- come

- com-e

- eat-PRS.3SG

- bala

- bala

- candy

- ‘Child eat candy’

- (Schmitt 1996: 234, examples 81c and 81d)

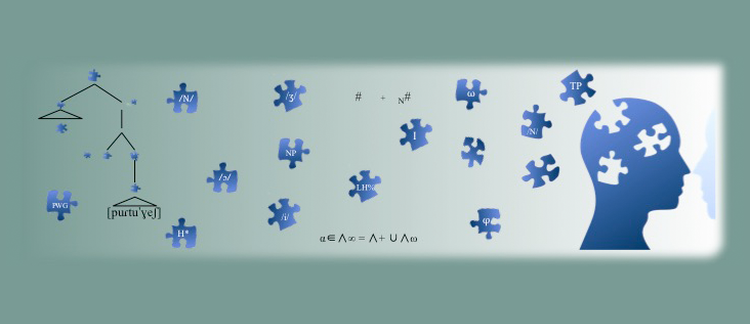

Since Schmitt (1996), much work has been done on the syntactic and semantic features associated with such nouns in Brazilian Portuguese. One of the most influential papers on the topic (Schmitt & Munn 1999) emerged after the publication of Chierchia’s nominal parameter (1998b). In his typology, Chierchia (1998b: 354–357) predicted the existence of three types of languages:1

[+arg, –pred] languages: classifier languages that have no plural marking and that allow for generalized bare arguments (such as Mandarin Chinese).

[–arg, + pred] languages: languages where only count nouns can be pluralized (such as French and Italian), but that either do not allow bare arguments at all (French) or that will have a limited distribution (Italian).

[+arg, + pred] languages: languages where only count nouns can be pluralized (such as English or German) and bare singulars are disallowed but bare plurals and bare mass nouns are not.

Chierchia (1998b)’s typology does not predict the existence of a language with a singular/plural distinction that also allows bare singulars. As such, Brazilian Portuguese challenged Chierchia’s typology precisely because of the availability of bare singulars in subject and object argument positions.

Since Chierchia’s nominal typology, much of the literature on Brazilian Portuguese explored the syntactic distribution and semantic interpretation of bare singulars (Beviláqua & Pires de Oliveira 2014, 2019; Ferreira 2010; Lima & Gomes 2016; Lima & Oliveira in press; Menuzzi, Silva & Doetjes 2015; Müller 2002; Müller & Oliveira 2004; Munn & Schmitt 2005; Paraguassu-Martins & Müller 2007; Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011a, 2011b; Pires de Oliveira & de Swart 2015; Schmitt & Kester 2005; Schmitt & Munn 1999, 2002, among many others). The vast majority of the examples discussed in this literature focused on one particular lexical class of nouns: nouns that denote concrete individuals. More specifically, the literature has focused on the contrast between objects and substances and how this contrast is manifested in the grammar.2 Nouns that denote non-concrete individuals (henceforth abstract nouns) are only marginally mentioned in most of the literature on the mass/count distinction. For example, as pointed out by Grimm (2014: 182), “while Chierchia (1998a: 69) claims that his system would extend to abstract nouns,” only one paragraph is devoted to the discussion of such nouns in Chierchia’s nominal mapping parameter. This is true not only for Chierchia (1998a, 1998b), but also for most contemporary formal and experimental approaches on the mass/count distinction. More recently, the interpretation and distribution of abstract nouns such as happiness and dancing started to gain more attention in the literature (see, Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008; Grimm 2012, 2014, 2016). Previous to our work, Resende (2016) presents a non-experimental discussion about the relationship between lexical aspect and countability for deverbal nouns in Brazilian Portuguese focusing on the contribution of the feature of telicity/atelicity to the count/mass interpretation of such nouns.

Against this background, in this article we intend to explore the interpretation of one class of abstract-denoting nouns in Brazilian Portuguese: nouns that denote events and that are derived from verbs, such as corrida ‘run’ and salto ‘jump’. Our goal is to discuss whether features of the events that these nouns denote – that is, whether they are associated with a durative or punctual event – impact the interpretation of such nouns when they are used as bare singulars (corrida ‘run’).

More specifically, we want to explore experimentally the following question: does the presence (bare plural) or absence (bare singular) of number morphology impact the interpretation of a deverbal noun? How does number morphology interact with the type of event such nouns denote?

In order to address these questions, we first present an overview on the literature on concrete object-denoting bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese (Section 1.1). Then, we present a quantity judgment task (based on the methods used by Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008) to explore the interpretation of deverbal nouns in Brazilian Portuguese (Sections 2–4). We conclude this article by arguing that this study’s results further support models of bare singular nouns that allow both count and mass interpretations (e.g., Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b). We show that the interpretation of bare singulars is impacted by lexical features of the noun root (in this specific case, the durative or punctual features that characterize the events the deverbal nouns denote).

1.1. Concrete denoting bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese

Much literature has explored the countability of concrete object-denoting nouns in Brazilian Portuguese (BP). The class of concrete object-denoting nouns includes nouns that denote substances (such as água ‘water’ and sangue ‘blood’) and that in most languages are encoded as mass nouns and nouns that denote objects, animals, and people (such as bola ‘ball’, cachorro ‘dog’, criança ‘child’) that in most languages are encoded as count nouns. The typology of countability (Chierchia 1998a, 1998b, 2010) considers the morphological and syntactic cues – that is, the distribution of numerals, number morphology, and determiners – and the lexical features of nouns – that is, whether they denote objects or substances – to distinguish count nouns from mass nouns across languages. In some languages (labelled “number marking languages” in Chierchia 2010), only count nouns such as cachorro ‘dog’ can be freely pluralized and combined directly with numerals (eu vi três cachorros ‘I saw three dogs’). In those languages (including English and Portuguese), mass nouns are only marginally acceptable in constructions where they are directly combined with numerals and/or are pluralized. For instance, a Brazilian Portuguese speaker may say dois cafés, por favor ‘can I have two coffees, please?’ in a restaurant, but in a situation where someone sees two drops of coffee on the ground, it is unlikely that that person will say eu vi dois cafés ‘I saw two coffees’. That is, while count nouns can be unrestrictedly combined with numerals directly, mass nouns can only do that in scenarios where portions are clearly individuated and a container is conventionalized, known in the literature as coercion or, more specifically, the universal packager (Doetjes 1997; Pelletier 1975, among many others).

One particular characteristic of count nouns in Brazilian Portuguese as compared to other number marking languages is that they may be used as bare singular arguments. As previously mentioned, while other number marking languages only allow bare plurals (Mary bought bananas), in Brazilian Portuguese, as originally observed by Schmitt (1996), both bare singulars and bare plurals are possible (Maria comprou banana/Maria comprou bananas). Formal and experimental semantics studies have explored the interpretation of bare singulars (Beviláqua, Lima & Pires de Oliveira 2016; Beviláqua & Pires de Oliveira 2014, 2019; Ferreira 2010; Lima 2015; Lima 2019; Lima & Gomes 2016; Lima & Oliveira in press; Menuzzi, Silva & Doetjes 2014; Müller 2002; Müller & Oliveira 2004; Munn & Schmitt 2005; Paraguassu-Martins & Müller 2007; Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011a, 2011b; Pires de Oliveira & de Swart 2015; Schmitt & Kester 2005; Schmitt & Munn 1999, 2002, among many others). One frequently discussed question in the literature about bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese is whether these nouns necessarily favour a mass interpretation over a count interpretation due to the absence of number marking. Some proposals (Müller 2002; Müller & Oliveira 2004; Munn & Schmitt 2005; Paraguassu-Martins & Müller 2007; Schmitt & Munn 1999) have claimed that these nouns are number-neutral (2). Being number-neutral, those nouns allow both singular and plural interpretations (3, 4), as their denotation includes singularities and pluralities.

| (2) | [[macçã]] = {apple1, apple2, apple3, apple1+apple2, apple2+apple3, apple1+apple3, apple1+apple2+apple3} |

- (3)

- João

- João

- John

- comprou

- compr-ou

- buy-PAST.3SG

- macçã.

- macçã.

- apple

- João bought (a) apple/apples.

- (Paraguassu-Martins & Müller 2007: 175, examples 18 and 19)

- (4)

- João

- João

- João

- comprou

- compr-ou

- buy-PAST.3SG

- maçã.

- maçã.

- apple.

- Ela/s

- Ela/s

- It/They

- está/estão

- está/estão

- be.SG/be.PL

- na

- na

- in.the

- cozinha.

- cozinha.

- kitchen.

- ‘João bought (a) apple/apples. It/they is/are in the kitchen’.

- (adapted from Schmitt & Munn 1999: 348, example 31/b and Ferreira 2010: 96, example 4)

These proposals do not predict the possibility of a mass (volume) interpretation of such nouns. Under this view, the absence of number morphology in bare singulars does not entail that these nouns have the same denotation as mass nouns. Schmitt and Munn (1999) showed that bare singulars (5) and substance-denoting mass nouns (6) do not share the same distribution in constructions that involve individuation:3

- (5)

- Criança

- criança

- child

- pesa

- pes-a

- weigh-PRS.3SG

- 20

- 20

- 20

- quilos

- quilo-s

- kilo-PL

- nesta

- nesta

- at.this

- idade.

- idade

- age

- ‘Children weight 20 kilos at this age’.

- (6)

- *Ouro

- ouro

- gold

- pesa

- pes-a

- weigh-PRS.3SG

- duas

- duas

- two

- gramas.

- grama-s

- gram-PL

Furthermore, Schmitt and Munn (1999) show that while bare singulars are acceptable in constructions with reciprocals (7) and reflexives (8), substance mass nouns do not occur in constructions that involve distribution over atomic individuals (9)–(10). As such, the authors concluded that bare singulars and mass nouns do not share the same denotation:

- (7)

- Criança

- criança

- child

- briga

- brig-a

- fight-PRS.3SG

- uma

- uma

- one

- com

- com

- with

- a

- a

- the

- outra.

- outra

- other

- ‘Children fight with each other’

- (Schmitt & Munn 1999: 348, example 35a)

- (8)

- Criança

- criança

- child

- sabe

- sab-e

- know-PRS.3SG

- se

- se

- REFL

- lavar

- lava-r

- wash-INF

- sozinha.

- sozinha

- alone

- ‘Children know how to wash themselves alone.’

- (Schmitt & Munn 1999: 349, example 35b)

- (9)

- *Ouro

- ouro

- gold

- realça

- realç-a

- enhance-PRS.3SG

- um

- um

- one

- atrás

- atrás

- behind

- do

- do

- of.the

- outro.

- outro.

- other

- Intended meaning: ‘Pieces of gold enhance each other’

- (10)

- *Ouro

- ouro

- gold

- realça

- realç-a

- enhance-PRS.3SG

- um

- um

- one

- ao

- ao

- to.the

- outro.

- outro.

- other

- Intended meaning: ‘Pieces of gold enhance each other’

- (Paraguassu-Martins & Müller 2007: 177, examples 27 and 29)

Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b) observed that when contrasting bare singulars with object-denoting mass nouns such as mobília ‘furniture’, a different picture emerges. Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011a: 237) observed that object mass nouns share distributional similarities with bare singulars; for example, they are compatible with distributive predicates (11) and reciprocals (12):

- (11)

- Mobília

- mobília

- furniture

- (nesta

- (nesta

- (in.this

- loja)

- loja)

- store)

- pesa

- pes-a

- weigh-PRS.3SG

- 20 quilos.

- 20 quilos

- 20 kilo-PL

- ‘Furniture (in this store) weighs 20 kilos.’

- (12)

- Mobília

- mobília

- furniture

- (desta

- (desta

- (of.this

- marca)

- marca)

- brand)

- encaixa

- encaix-a

- fit-PRS.3SG

- uma

- uma

- one

- na

- na

- in.the

- outra.

- outra.

- other.

- ‘Pieces of furniture (of this brand) fit into each other.’

- (Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b: 2157, examples 10a and 11a)

Based on these pieces of evidence, Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b) claimed that bare singulars are kind-denoting terms4 that share similarities with object mass nouns, such as furniture, that denote individuated entities but are grammatically mass nouns.

From the observation that bare singulars are similar to object-denoting mass nouns, Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b), based on Rothstein (2010), build an analysis for bare singulars according to which count and mass nouns are derived from an abstract root noun Nroot. The derivation of a mass noun is obtained by applying the operation MASS to Nroot (13):

| (13) | Mass nouns (Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b: 2163): | |

| a. | Nmass = MASS (Nroot) = (∩Nroot) = λw. ⊔M(Nroot.w). The extension of a mass noun is thus MASS (Nroot) (w0) | |

| b. | ∪ is the function from kind-extensions to sets of individuals such that for every kind-extension k(w0): ∪(k(w0)) = λx.x ⊑M k(w0). | |

As presented in (13), “mass nouns denote the kind associated with the root noun, while the predicative use of a mass noun can be recovered by the ∪ function. The ∪ function, when applied to the kind, will give back the set of instantiations of the kind in w0, i.e., the subset of entities in Nroot which exist in w0” (Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b: 2163).

As for singular count nouns,5 the operation COUNTk applies to Nroot and picks out “the set of ordered pairs {<d,k>: d ε N ∩ k}, i.e., the set of entities in Nroot which count as one in context k” (Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b: 2164).6 The critical aspect of their analysis is that bare singular nouns allow both a mass and a count interpretation. This is possible under their analysis because Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b: 2164) postulated that languages vary in whether they follow or not the “either/or” principle (14):

| (14) | The “either/or” principle for the derivation of nouns |

| Either COUNTk or MASS applies to a root noun, but not both. |

The authors noted that in English, the principle in (14) “is the default situation, there is a limited set of cases in which both MASS and COUNTk may apply to Nroot” (Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b: 2164). On the other hand, in languages like Brazilian Portuguese, the principle described in (14) does not apply. As such, the authors proposed that all nouns allow a count and a “lexicalized mass” counterpart. The lexicalized mass counterpart will surface as bare singulars given that mass nouns are morphologically singular. Nouns on which the operation COUNT can apply will also allow the operation MASS. That is, in languages like Brazilian Portuguese, count nouns will always have a mass counterpart; nouns on which the operation COUNT cannot apply, on the other hand, will not have a count counterpart, unless additional operations apply (i.e., coercion).

Rothstein and Pires de Oliveira (2011b) presented two predictions that are borne out from their proposal. First, bare singulars may occur as complements of mass quantifiers (15):

- (15)

- Context: João is travelling and has a huge amount of books on his hands. His mother can make the following remarks:

- a.

- Quanto

- quanto

- how.much-SG

- livro

- livro

- book

- você

- você

- 2SG

- acha

- acha

- think-PRS.2SG

- que

- que

- that

- pode

- pod-e

- can-PRS.2SG

- carregar!?

- carrega-r

- carry-INF

- ‘What quantity of book can you carry?!’

- b.

- É

- é

- BE.PRS.3SG

- muito

- muito

- much-SG

- livro

- livro

- book

- pra

- pra

- for

- você

- você

- 2SG

- levar!

- leva-r

- carry-INF

- ‘That quantity of book(s) is too much for you to carry.’

- (Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein 2011b: 2172, examples 53a and 53b)

In (15), as discussed by the authors, the mother refers to the volume/weight of the books being carried; so volume, not cardinality, is the feature that is salient in the context; we could have a few very heavy books. Second, in comparatives, bare singulars allow both a comparison in terms of volume and cardinality (16):

- (16)

- Esse

- esse

- this

- jardim

- jardim

- garden

- tem

- te-m

- have-PRS.3SG

- mais

- mais

- more

- pedra

- pedra

- stone

- do

- do

- of.the

- que

- que

- that

- aquele.

- aquele

- that

- ‘This garden has more stone than the other one’

- (17)

- Esse

- esse

- this

- jardim

- jardim

- garden

- tem

- te-m

- have-PRS.3SG

- mais

- mais

- more

- pedras

- pedra-s

- stone-PL

- do

- do

- of.the

- que

- que

- that

- aquele.

- aquele

- that

- ‘This garden has more stones than the other one’

- (Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein 2011b: 2173, examples 60a and 61a)

While in sentences with bare singulars (16), the bare singular noun (pedra ‘stone’) allows for a comparison in terms of volume (size of the stones) and in terms of cardinality (number of stones), when the sentence includes a bare plural (pedras ‘stones’), only a cardinal interpretation is available.

Comparatives have long been discussed in the mass/count literature as a reliable diagnostic for distinguishing count nouns from mass nouns (Bale & Barner 2009). In comparative structures, count nouns are more likely to be evaluated in terms of cardinality, while mass nouns are evaluated in terms of volume. Most of the experimental studies on this topic in Brazilian Portuguese involve quantity judgment tasks (see, e.g., Beviláqua & Pires de Oliveira 2014, 2019; Lima & Gomes 2016), which are characterized by comparison constructions.

Quantity judgments (see Barner & Snedeker 2005) consist of comparison tasks, where participants are presented with two characters: one (A) that has large quantities of X (e.g., two large portions of X or two large individual Xs) and another (B) that has a more numerous quantity of Xs (e.g., six portions of X, six individual Xs), where each portion/individual is of a smaller size. The participants are then asked, “Who has more X?” For example, in order to answer the question “Who has more ketchup?” participants are presented with two big portions of ketchup (A) and with six small portions of ketchup (B) (Figure 1).

Sample stimuli, quantity judgment tasks (Barner, Li & Snedeker 2010: 4).

Quantity judgment tasks have shown that English speakers (16 adults and 16 four-year-olds) choose A over B when answering questions that include mass nouns (such as ketchup) (0% cardinal answers) and that they choose B over A when answering questions that include count nouns (such as pens) (100% cardinal answers) (Barner & Snedeker 2005). It is important to note that in English a small set of count nouns (so-called “flexible” nouns; Barner & Snedeker 2005; Gillon 1992; Rothstein 1999, 2004, 2010, among many others) can be used both in their pluralized form (count syntax), as in who has more chocolates?, and in their bare form (mass syntax), as in who has more chocolate? That is the case for nouns such as stone, chocolate, and paper. In a study with English-speaking adults and children (16 adults and 12 four-year-old children), Barner and Snedeker (2005) found that a volume interpretation is favoured when count nouns are used with mass syntax (who has more chocolate?), while a cardinal interpretation is favoured when they are used with count syntax (who has more chocolates?) (count syntax: 97% of cardinal answers; mass syntax: 3% of cardinal answers).

In the same study, when asked a question that included an object mass noun (who has more furniture?), English speakers (16 adults and 16 four-year-olds) favour a cardinal interpretation over a volume interpretation (97% of cardinal answers) (Barner & Snedeker 2005). That is, despite being grammatically mass nouns, these nouns allow a cardinal interpretation. These results are important particularly when contrasted with the results for the same type of task with flexible nouns, like stone, that can be used bare or pluralized. Bare flexible count nouns trigger, in English, a mass interpretation, as summarized in Table 1.

Summary: results of quantity judgment tasks across different types of nouns in English (based on Barner & Snedeker 2005).

| Noun | Quantity judgment tasks (preferred answer, in English) |

|---|---|

| stone (flexible count noun, mass syntax) | mass interpretation |

| stones (flexible count noun, count syntax) | count interpretation |

| furniture (object mass noun) | count interpretation |

| shoes (non-flexible count noun) | count interpretation |

| water (substance denoting noun) | mass interpretation |

In sum, the results of quantity judgment tasks in English illustrate that while pluralized nouns are only associated with quantification of individuals, mass nouns of different types (water/furniture7) and bare count nouns (stone) do not “force an unindividuated construal” (Barner & Snedeker 2006: 167). Barner and Snedeker (2006) called this the Number Asymmetry Hypothesis.

As previously discussed in this article, and following Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b), Brazilian Portuguese and English are not similar with respect to the distribution of bare singulars. In English, as discussed by several authors (e.g., Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b; Schmitt & Kester 2005), only a small class of count nouns allow for this alternation (bare/plural). As previously discussed, in English, the principle described in (14) applies to all nouns. That is, only COUNTk or MASS will apply to each Nroot noun. In Brazilian Portuguese, the availability of bare singulars is not restricted to a small class of nouns, suggesting that the principle described in (14) does not apply to this language. That is, in Brazilian Portuguese, but not in English, all count nouns seem to have bare and plural counterparts.

The difference in the status of bare singulars (flexible nouns) in English (used in “lexically restricted contexts”; Schmitt & Kester 2005: 237) and bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese becomes clear when we contrast the interpretation of these nouns in these two languages. As previously observed, in English, the small class of nouns that allow such variation seems to be interpreted as always referring to volume (see Table 1) when bare. That is, the absence of number naturally triggers a mass interpretation for such nouns. In Brazilian Portuguese, the same does not hold: as shown by Pires de Oliveira and Beviláqua (2006) and Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b), bare singulars allow both cardinal and volume interpretations.

The prediction that bare singulars allow cardinal and volume readings is borne out in Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein’s (2011b) analysis. However, if both readings are possible for bare singulars, why the cardinal interpretation seems to be favoured over the volume interpretation in neutral contexts needs to explained. Lima and Gomes (2016: 206) proposed two factors to account for these facts: 1) a natural atomicity bias (“nouns that denote kinds whose canonical instances are individuals more likely to be grammaticalized as a count noun and to be interpreted as referring to cardinalities in Brazilian Portuguese”) and 2) lexical statistics, based on Samuelson and Schiffer (2011) (“a BS noun like livro is more likely to be interpreted as a count noun due to the high frequency of count interpretations of other forms of the same lexeme (such as the plural form livros)”). If a natural atomicity bias exists, one interesting question is whether other lexical features could impact the interpretation of bare singulars. While much work has been done on the interpretation of concrete object-denoting nouns in Brazilian Portuguese, the literature on Brazilian Portuguese has not yet addressed the interpretation of bare abstract nouns derived from verbs (henceforth “deverbal nouns”). The investigation of deverbal nouns seems critical for this debate for two reasons.

First, as previously mentioned, prior to this study, no experimental study has focused on non-concrete-object-denoting nouns in Brazilian Portuguese. Second, by investigating abstract nouns and, more specifically, deverbal nouns, we can explore the lexical features of the Nroot and the potential impact of those features on the interpretation of bare singulars. In other words, while according to Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b), among others, bare singulars allow both count (cardinal) and mass (volume) interpretations, lexical information from the root might determine the more likely interpretation for different nouns.

As such, the main goal of this article is to investigate the interpretation of deverbal nouns. Deverbal nouns are relevant to this debate as the verbs they are derived from have inherent aspectual features and might be critical for showing that while bare singulars allow both readings, the ultimate interpretation of a noun might be impacted by the features encoded by the root. In sum, we want to explore whether aspectual features impact the interpretation of such nouns with respect to countability and how these aspect features interact with plurality (or lack thereof).

1.2. Studies on abstract nouns

Across languages, most studies on countability are based on concrete object-denoting nouns. Studies that explore the countability of abstract nouns mostly focus on English and include formal, quantitative approaches to the topic (see Grimm 2014 for a review of the literature and Grimm 2016 for a case study on the noun crime) and experimental studies that explore the interpretation of deverbal nouns (see Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008).

Barner, Wagner, and Snedeker (2008) explored the impact of the noun form (bare or pluralized) on the interpretation of English deverbal nouns. The authors explored this question by means of a quantity judgment task. The authors manipulated two factors: noun form (nouns that cannot be pluralized – dancing, jumping – and nouns that can be pluralized – dance(s), jump(s)) and event type (durative vs. punctual). Therefore, four conditions were manipulated: punctual mass, punctual count, durative mass, and durative count. Participants were exposed to a short narrative followed by a target question to which two answers were available, as illustrated in (18) and (19):

| (18) | Jerry and Jake love to drive. Last week: | |||

| Jerry drove four times: | Jake drove two times: | |||

| To the store on Monday (1 mile) | To the office on Monday (20 miles) | |||

| To the beach on Saturday (2 miles) | To the park on Tuesday (40 miles) | |||

| To the barber on Thursday (1 mile) | ||||

| To the dentist on Friday (3 miles) | ||||

| Question: Overall, who did more driving? (durative, mass syntax)/drives? (durative, count syntax) | ||||

| Possible answers: | Jerry | Jake | ||

| (Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008: 828, example A, Appendix B) | ||||

| (19) | Jerry and Jake like to jump high in the air. Yesterday: | ||

| Jerry jumped four times: | |||

| Before breakfast, he jumped 2 in. off the ground. | |||

| At lunch, he jumped 4 in. off the ground. | |||

| At work, he jumped 3 in. off the ground. | |||

| Before bed, he jumped 2 in. off the ground. | |||

| Jake jumped two times: | |||

| Before lunch, he jumped 14 in. off the ground. | |||

| At work, he jumped 18 in. off the ground. | |||

| Question: Overall, who did more jumping? (punctual, mass syntax)/jumps? (punctual, count syntax) | |||

| Possible answers: | Jerry | Jake | |

| (Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008: 829, example C, Appendix B) | |||

Barner, Wagner, and Snedeker (2008) found that non-pluralized durative deverbal nouns (driving) were more likely to have a mass interpretation than non-pluralized durative deverbal nouns (drives). Contrariwise, non-pluralized punctual deverbal nouns (jumping) and pluralized punctual deverbal nouns (jumps) are equally likely to be associated with a count interpretation. As such, the NP meaning was critical for the interpretation of deverbal punctual nouns as their interpretation was not solely dependant on the form of the noun (bare or pluralized).

As previously mentioned, in Brazilian Portuguese, a less explored field of research is the interpretation of deverbal nouns with respect to countability. Two aspects of Brazilian Portuguese make this language an interesting test case for the impact of the absence/presence of number morphology on the interpretation of nouns. First, Brazilian Portuguese, unlike English, is a language where bare singulars are not restricted to marked uses and are frequently used in the object position of episodic predicates (see Pires de Oliveira 2014 for a review of the literature on bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese8). Second, as discussed in Section 1.1, studies have shown that (concrete object-denoting) bare singulars are not necessarily interpreted as mass nouns. Instead, some studies suggest that the lexical meaning (i.e., whether a noun denotes an object or a substance) drives the interpretation of concrete object-denoting count nouns in neutral contexts. In other words, while both cardinal and volume interpretations are licensed by bare singulars, a cardinal interpretation seems to be overwhelmingly preferred over a volume interpretation in neutral contexts (i.e., when a particular interpretation is not favoured by the context; see Lima & Gomes 2016).

In this paper, we discuss the interpretation of deverbal nouns with respect to countability in Brazilian Portuguese. More specifically, we investigate the interaction between the lexical meaning of the nouns (whether they refer to iterative or continuous events) and noun form (bare or pluralized). According to the Number Asymmetric Hypothesis (Barner & Snedeker 2006), mass syntax (non-pluralized nouns) “is unspecified and permits comparison based on an unbounded range of measuring dimensions including mass, volume, time and crucially number” (Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008: 807). Given that the lexical meaning of the noun impacts the interpretation of concrete bare singulars in neutral contexts, we predict that a similar pattern will be observed for deverbal nouns in Brazilian Portuguese. That is, bare singulars denoting continuous events (derived from durative verbs) should be less likely to license a count interpretation compared to nouns that denote iterative events (derived from punctual verbs). These predictions are explored based on a quantity judgment task in Brazilian Portuguese that replicates Barner, Wagner, and Snedeker’s (2008) studies in English.

2. A quantity judgment task with deverbal nouns in Brazilian Portuguese

Aspectual information is brought to sentences across languages either through grammatical elements or through the inherent meaning of predicates (Comrie 1976; Smith 1997, among others). In this article, we are especially interested in the latter, which is called “situation type” (Smith 1997) or “lexical aspect” (Rothstein 2004). Smith (1997), based on Vendler (1967), who proposed four verb types, states, activities, accomplishments, and achievements, analyzed such verb types according to their temporal features – static vs. dynamic, telic vs. atelic, and durative vs. instantaneous – and proposed a fifth verb type – semelfactive – as summarized in Table 2.

Features of verb types based on Smith (1997: 20).

| Situations | Static | Durative | Telic |

|---|---|---|---|

| States | [+] | [+] | [–] |

| Activities | [–] | [+] | [–] |

| Accomplishments | [–] | [+] | [+] |

| Semelfactives | [–] | [–] | [–] |

| Achievements | [–] | [–] | [+] |

Our main study contrasted nouns that denote durative and punctual events in Brazilian Portuguese. While durative events take place over a certain amount of time, punctual events take place in a moment (Comrie, 1976; Smith 1997). In other words, and as highlighted by Barner, Wagner, and Snedeker (2008), punctual events are characterized by atomic events that have clear start and end points. As such, the repetition of a punctual event (such as jump) implies several bounded events of the same type. On the other hand, durative events (such as walk) are unbounded and are characterized as events that can take place over an extended period of time, continuously.

The classification of verbs as durative or punctual – or as activities, achievements, semelfactives, etc. – is not unanimous in the aspectual literature. Thus, while taking into consideration examples of prototypical verbs presented as activities by Vendler (1967) and Dowty (1979) or as semelfactives by Smith (1997) and Katalin (2011), in order to select the verbs for the main study, we did an initial stimuli norming study (based on Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008, Study 1) where the participants had to evaluate different verbs as iterative events or continuous events, which implied the repetition of punctual events or the lasting in time of durational ones, respectively. A total of 27 verbs were evaluated by the participants (66 Brazilian Portuguese speakers) in this task. For our main study (that was answered by a different group of participants), we selected nine punctual verbs that were evaluated as iterative events in at least two-thirds of the trials. We also selected nine durative verbs that were evaluated as durative events in at least two-thirds of the trials (see Appendix 1).

In selecting the verbs for this study, we focused on verbs that were classified as [-telic], according to Smith (1997). For that reason, all durative verbs used in this study were activities. Deverbal nouns derived from accomplishments were avoided because they are characterized as telic; on the other hand, activities, such as caminhada(s) ‘walk(s)’ and pulo(s) ‘jump(s)’ in constructions such as fazer caminhada(s) lit.: ‘to do walking/to make walks’ and dar pulo(s) lit.: ‘to do jumping/to do jumps’ are characterized by unbounded events. Deverbal nouns derived from states cannot occur in a light verb construction in Brazilian Portuguese (e.g., *dar gostada(s) ‘to do liking/to make likes’) due to its [+static] feature (Scher 2005: 121); for that reason, they were not included in our study.

As for punctual verbs, all but one verb used in this study were semelfactives; one was an achievement (morder ‘to bite’). As demonstrated in Table 2, according to Smith (1997), semelfactive verbs are characterized as [–telic]. The one achievement verb used in the main test was judged similarly to the semelfactive ones in the first stimuli norming study (Appendix 1), which justifies its inclusion in the main study.

Based on the results of the first stimuli norming study and selection of verbs/nouns based on this first task, we did a second stimuli norming study (also based on Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008) in order to choose the dimensions of comparison to be used in the main study (Appendix 2). Out of a list that included eight options (volume, height, time, value, distance, intensity, depth, and area), the participants (who only participated in this study, 90 Brazilian Portuguese speakers) had to choose as many dimensions as they thought they would use for measuring an event (e.g., se você tivesse que responder a pergunta “Quem fez mais caminhada/caminhadas?”, quais critérios você usaria? [If you had to answer the question “Who did more walking/took more walks?” which criteria would you use?]). The most frequent non-number dimension selected by the participants for each verb was used to build the contexts in the main study (Table 3).

Most selected non-number dimensions in the second stimuli norming study and included in the main study.

| Durative | Punctual | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| caminhada ‘walk’ | distance | grito ‘scream’ | intensity |

| corrida ‘run’ | distance | salto ‘jump’ | height |

| pedalada ‘pedalling’ | distance | mordida ‘bite’ | intensity |

| passeio ‘promenade’ | time | belisco ‘pinch’ | intensity |

| fala ‘talk’ | time | beijo ‘kiss’ | time |

| pintura ‘painting’ | area | espirro ‘sneeze’ | time |

| costura ‘sewing’ | area | chute ‘kick’ | intensity |

| leitura ‘reading’ | time | pulo ‘jump’ | height |

| desenho ‘drawing’ | area | abraço ‘hug’ | time |

Among the selected nouns, four were nominalizations formed by a process that also generates a participle verb form: X (the verb stem) + -ada (three durative nouns – caminhada ‘walk’, corrida ‘run’, and pedalada ‘pedal’ – and one punctual noun – mordida ‘bite’). These four deverbal nouns could not be created by other means in Brazilian Portuguese and that is why they were included in the list of the chosen nouns. It is important to clarify that all other nouns used in the study could be formed by this same process of nominalization, but this (X + -ada) nominalization process was avoided because a deverbal noun formed via this nominalization process could promote a “diminutive effect” (Scher 2004: 103–104); that is, in dar uma pintada ‘give a paint’, it is implied that the event was short, which is an effect we wanted to avoid.

3. Main study: materials and methods

In a quantity judgment task (based on Barner, Wagner & Snedeker 2008 for English), we manipulated two conditions: the type of the event (durative or punctual) and the question form (verb, non-pluralized noun, pluralized noun):

| (20) | Question form 1: verb |

| Durative: Quem caminhou mais? ‘Who walked more?’ | |

| Punctual: Quem pulou mais? ‘Who jumped more?’ |

| (21) | Question form 2: singular noun |

| Durative: Quem fez mais caminhada? ‘Who did more walking?’ | |

| Punctual: Quem deu mais pulo? ‘Who did more jumping?’ |

| (22) | Question form 3: plural noun |

| Durative: Quem fez mais caminhadas? ‘Who took more walks’? | |

| Punctual: Quem deu mais pulos? ‘Who did more jumps?’ |

Participants were presented with a short context followed by a target question. The short contexts presented two characters: one that performed fewer, but longer events (e.g., two long walks for two hours each – mass answer) and another that performed a higher number of short events (e.g., four short walks for 15 minutes each – count answer). Each participant answered 54 questions: nine questions including a durative verb/deverbal noun; nine questions including a punctual verb/deverbal noun; and 36 fillers unrelated to the manipulation. Participants were presented with only one type of question (non-pluralized noun, plural noun, or verb). Thirty-nine participants answered the list where all nouns were pluralized; 43 participants answered the list where all nouns were non-pluralized; 66 participants answered a list where the target sentence included a verb.

| (23) | Example of experimental item (durative) | |

| João e Pedro gostam de caminhar. Na última semana: | ||

| [João and Pedro like to walk. Last week:] | ||

| João caminhou 4 vezes (count answer): | ||

| [João walked four times:] | ||

| Segunda [Monday]: 1 km. | ||

| Terça [Tuesday]: 2 km. | ||

| Quarta [Wednesday]: 1 km. | ||

| Quinta [Thursday]: 3 km. | ||

| Pedro caminhou 2 vezes (mass answer): | ||

| [Pedro walked two times:] | ||

| Segunda [Monday]: 10 km. | ||

| Terça [Tuesday]: 5 km. | ||

| Target sentence (verb list): Quem caminhou mais? | [Who walked more?] | |

| Target sentence (non-pluralized noun): Quem fez mais caminhada? | [Who did more walking?] | |

| Target sentence (plural noun): Quem fez mais caminhadas? | [Who took more walks?] | |

| (24) | Example of experimental item (punctual) | |

| João e Pedro amam pular na cama elástica. Na última semana: | ||

| [João and Pedro love to jump on the trampoline. Last week:] | ||

| João pulou 4 dias [João jumped on four days]: | ||

| Segunda [Monday]: 5cm de altura [height: 5 cm]. | ||

| Quarta [Wednesday]: 2cm de altura [height: 2 cm]. | ||

| Sexta [Friday]: 10cm de altura [height: 10 cm]. | ||

| Sábado [Saturday]: 2cm de altura [height: 2 cm]. | ||

| Pedro pulou 2 dias [Pedro jumped two days]: | ||

| Terça [Tuesday]: 20cm de altura [height: 20 cm]. | ||

| Quinta [Thursday]: 30cm de altura [height: 30 cm]. | ||

| Target sentence (verb list): Quem pulou mais? | [Who jumped more?] | |

| Target sentence (singular): Quem deu mais pulo? | [Who did more jumping?] | |

| Target sentence (plural): Quem deu mais pulos? | [Who did more jumps?] | |

As illustrated by example (23), in constructions with durative denoting nouns, we used the light verb fazer ‘to do/make’: Quem fez mais caminhada? ‘Who did more walking?’ and Quem fez mais caminhadas? ‘Who took more walks?’ On the other hand, as illustrated by example (24), in constructions with punctual denoting nouns, we used the light verb dar ‘to give’: Quem deu mais pulo? ‘Who did more jumping?’ or Quem deu mais pulos? ‘Who did more jumps?’

The choice of light verb to create the target sentences with durative and punctual deverbal nouns is derived from the fact that, in Brazilian Portuguese, the use of the light verb fazer ‘to do/make’ with all punctual nouns would result in ungrammatical sentences, such as *Quem fez mais pulo? ‘Who did more jumping?’ *Quem fez mais grito? ‘Who did more screaming?’ Similarly, many durative nouns in constructions with the light verb dar ‘to give’ would either be considered ungrammatical or would be interpreted as referring to an object, rather than to an event. For example, Quem deu mais pintura? ‘Who did more painting?’ implies that we are talking about physical paints rather than the event of painting. Alternatively, we could have used target sentences such as Quem deu mais pintada?, Quem deu mais costurada?, and Quem deu mais desenhada?, which are legitimate in Brazilian Portuguese. However, such sentences were avoided due to the “diminutive effect” (Scher 2004) of constructions such as dar ‘to give’ + X-ada, as previously mentioned (Section 2), which would be incompatible with some of the contexts created in the target items. For example, in one item, we specified that a person is painting a bridge and the Maracanã stadium wall, which suggests a professional activity, not an incomplete or unstructured one, which would be incompatible with dar pintada lit.: ‘to give painting’. Hence, in order to provide uniform target sentences, all durative deverbal nouns were associated with the light verb fazer ‘to do/make’ and all punctual deverbal nouns were associated with the light verb dar ‘to give’.

Our baseline list included target questions with verbs (quem andou mais? ‘who walked more?’ / quem pulou mais? ‘who jumped more?’). It was critical to first determine whether durative and punctual verbs were indeed associated with different responses. That is, for the critical questions that included verbs, we expected that durative verbs would be more frequently associated with a mass answer; by contrast, punctual verbs were expected to be associated with a count answer.

Our second prediction was that for the critical questions that included bare singular nouns derived from punctual verbs, a count answer would be favoured. By contrast, we expected that a mass interpretation would be favoured for bare singular nouns derived from durative verbs. Our third and final prediction was that, if the plural morpheme blocks a mass interpretation (Müller 2002; Pires de Oliveira & Rothstein 2011b), then we would expect pluralized nouns to strongly favour a count answer, regardless of the lexical features of the noun.

4. Results

As shown in Figure 2, the punctual aspectual feature was associated with a much higher relative frequency of cardinality responses with verbs and bare singulars. Plural nouns were associated with a high relative frequency of cardinality responses regardless of durativity/punctuality.

We used mixed effect logistic regression to analyze the probability of a cardinality response in experiment 1. Our model used items and participants as random effects, which was the maximal random-effects structure justified by the model comparison. We see in Figure 3 that there was significant interaction between aspect (durative/punctual) and category (verb, non-pluralized noun, pluralized noun), and there were significant main effects of each variable.

The marginal effects of the interaction term from our mixed-effects model are shown in Figure 4. We see that while durative verbs and bare singulars are more likely to receive a volume than a cardinality interpretation, those that have a punctual aspectual feature are more likely to receive a cardinality interpretation. By contrast, plural nouns are very likely to receive a cardinality interpretation regardless of their aspectual features.

In sum, the results confirmed our initial predictions. In the verb condition, nouns denoting durative events were much less likely to be associated with the count response (28.5% of count/cardinal responses) compared to punctual events (75.2% of count/cardinal responses). In the singular noun condition, the count response is more likely when the deverbal noun is derived from a punctual event (87% of count/cardinal responses) rather than a durative event (41.6% of count/cardinal responses). In the plural noun condition, punctual and durative events equally favour a count response (97.2% and 87.1%, respectively).

5. Discussion

The results of this study show that deverbal bare singulars allow count and mass interpretations depending on the durativity/punctuality of the verbs they are derived from. Nouns that denote punctual events, regardless of their form (bare or pluralized), were more likely than nouns that denote durative events to be associated with a cardinal/count response.

These results provide further empirical support for the dissociation between mass-count syntax (i.e., absence or presence of number morphology on nouns) and countability. As predicted by the Number Asymmetry Hypothesis, mass syntax (absence of number morphology) does not trigger a mass/volume interpretation; that is, as predicted by Barner, Wagner, and Snedeker (2008), different dimensions (number, intensity, distance, volume, etc.) may be associated with a noun unmarked for number, while count syntax (pluralized nouns) is more likely to trigger a count/cardinal interpretation. In other words, these results provide further support for the claim that count syntax is not a requirement for counting.

Most importantly, these results are also compatible with Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein’s (2011b) proposal, according to which bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese are kind-denoting terms that allow both cardinal and volume interpretations. The present study shows that for deverbal nouns, a cardinal or volume interpretation for deverbal bare singulars depends on the lexical features of the verb the noun derives from: while nouns that denote punctual events favour a cardinal interpretation, nouns that denote durative events do not show the same preference. The results for durative deverbal nouns (41% of count/cardinal responses) are meaningful because they show that an unbounded event allows a range of interpretations that punctual events do not. In other words, it is not mass syntax per se that determines one interpretation or another; mass syntax allows either count or mass interpretations of nouns. The lexical features determine a particular interpretation of a noun. In sum, we have shown that lexical features of nouns – such as durativity/punctuality – impact the interpretation of bare abstract (more specifically deverbal) nouns in the same way as they impact the interpretation of bare concrete nouns (object-denoting bare singulars are more likely to be associated with cardinal responses). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental investigation of deverbal bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese.

One remaining question is whether the obtained results were at least in part influenced by the type of light verb used in the materials of the main study, since durative deverbal nouns were associated with the light verb fazer ‘to do/make’ (Quem fez mais caminhada? ‘Who did more walking?’) and punctual deverbal nouns were associated with the light verb dar ‘to give’ (Quem deu mais pulo? ‘Who did more jumping?’). As discussed in Section 2, it was not possible to choose a single light verb for all constructions with punctual/durative deverbal nouns. While durative nouns were compatible with fazer ‘to do/make’, punctual verbs were not. Contrariwise, while constructions with punctual nouns were compatible with the light verb dar ‘to give’, constructions with durative nouns were either ungrammatical or resulted in an interpretation where the speaker was referring to an object, rather to an event (Quem deu mais pintura? ‘Who gave more paints?’ is interpretable in a scenario where two or more people donated paints to a museum and one is asking who donated more paints). We hypothesize that since light verbs “seem to modulate or structure a given event predication, but not supply their own event” (Butt 2010: 72), the aspectual value of the deverbal noun – durative or punctual – is the major contribution to the semantics of the construction in the analyzed constructions.

We would like to conclude this paper by highlighting an interesting distinction between Brazilian Portuguese (a language where bare singulars are frequently licensed in episodic sentences) and English (a language where only a small set of nouns freely alternate between a mass syntax and a count syntax). As previously mentioned, in English, lexical semantics is overruled by mass syntax in the interpretation of sentences such as ‘Who has more stone?’ That is, in quantity judgment tasks (Barner & Snedeker 2005), English speakers point to a large stone rather than three small stones in order to answer this question. This could be partially motivated by the fact that the majority of nouns used in mass syntax are mass nouns in this language (interpreted preferentially in terms of size dimensions, such as volume, rather than cardinality). In Brazilian Portuguese, the use of bare singulars is not at all restricted to volume scenarios and is not marginal, or restricted to a small set of nouns. This is one of the possible readings of such nouns, but a cardinal/count reading is frequently available. As such, the difference between these two languages with respect to the interpretation of concrete object-denoting bare nouns might also be motivated by the frequency of use of bare nouns with a count interpretation. In other words, the level of impact of lexical semantics and count-mass syntax in the interpretation of nouns might be determined by the statistical frequency of a noun form with a particular interpretation (see Samuelson & Schiffer 2011) and by contextual information (as shown by Beviláqua & Pires de Oliveira 2014 for bare singulars in volume contexts).

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Stimuli norming study 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.241.s1

Stimuli norming study 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.241.s1

Notes

- Chierchia (1998b) notes that nouns can be arguments (arg), in which case they denote kinds (type e), or they can be predicates (pred), in which case they denote sets of entities (type <e,t>). [^]

- In the field of language development, much of the literature was devoted to exploring the relationship between pre-linguistic semantic categories and syntactic categories of nouns (see MacNamara 1972, 1982, among others). That is, researchers have explored how children might infer the categories of count and mass from their knowledge of what objects and substances are. This topic continues to be explored in this literature, taking into consideration cross-linguistic diversity. See Li, Dunham, and Carey (2009) and literature quoted therein. [^]

- Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011a, 2011b) showed that count nouns such as linha ‘thread’ and reta ‘line’ do not seem to be compatible with distributive predicates and reciprocals. This class of count nouns is taken by Rothstein (2010) as a central piece of evidence that atoms may be contextually defined; in other words, we do not need natural atoms for counting in the grammar. [^]

- That bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese are kind-denoting terms was first proposed by Schmitt (1996). [^]

- Under Pires de Oliveira and Rothstein (2011b: 2164)’s analysis, plural count nouns are derived via the plural operation * (Link 1983), which “takes a set of atomic entities and returns the set of all available sums of these entities.” [^]

- The idea that nouns are originally unmarked for count or mass is contemplated in other analyses of bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese. Schmitt and Kester (2005: 242) built on Borer’s (2005) analysis, according to which nouns are derived from a listeme that is mass by default. Under this analysis, count nouns are derived by means of the projection of a classifier phrase. As such, bare singulars “are systematically interpreted as count and not mass.” Because the authors’ analysis is based on the assumption that a mass interpretation of bare singulars is only available via coercion (Schmitt & Kester 2005: 246), in this proposal, the classifier phrase does not seem to be optional for singular count nouns. [^]

- Grimm and Levin (2012) showed that the interpretation of furniture-type of nouns in quantity judgment tasks can be impacted by the context. Features such as functionality and heterogeneity impact the interpretation of such nouns. See Grimm and Levin (2012) for details. [^]

- It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the availability and interpretation of bare singulars in subject position. Some literature has addressed this topic. See Menuzzi, Silva, and Doetjes (2015) and Santana and Grolla (2018) for details. [^]

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers and audience at the CLA 2018 conference for their comments. We would like to take the opportunity to thank both Journal of Portuguese Linguistics reviewers for their comments. We would also like to thank the participants of our studies and Renato Tomaz da Conceição for helping us advertise them. All usual disclaimers apply.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Bale, A. C., & Barner, D. (2009). The interpretation of functional heads: Using comparatives to explore the mass/count distinction. Journal of Semantics, 26(3), 217–252. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffp003

Barner, D., Li, P., & Snedeker, J. (2010). Words as windows to thought: the case of object representation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(3), 195–200. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410370294

Barner, D., & Snedeker, J. (2005). Quantity judgments and individuation: Evidence that mass nouns count. Cognition, 97(1), 41–66. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2004.06.009

Barner, D., & Snedeker, J. (2006). Children’s early understanding of mass-count syntax: Individuation, lexical content, and the number asymmetry hypothesis. Language Learning and Development, 2(3), 163–194. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/s15473341lld0203_2

Barner, D., Wagner, L., & Snedeker, J. (2008). Events and the ontology of individuals: Verbs as a source of individuating mass and count nouns. Cognition, 106(2), 805–832. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.05.001

Beviláqua, K., Lima, S., & Pires de Oliveira, R. (2016). Bare nouns in Brazilian Portuguese: An experimental study on grinding. Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication, 11, 1–25. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4148/1944-3676.1113

Beviláqua, K., & Pires de Oliveira, R. (2014). Brazilian bare phrases and referentiality: Evidences from an experiment. Revista Letras, 90, 253–275. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5380/rel.v90i2.37234

Beviláqua, K., & Pires de Oliveira, R. (2019). O singular nu no Inglês e no Português Brasileiro: Abordagens experimentais sobre atomicidade. Diacrítica, 33(2), 156–177. DOI: http://doi.org/10.21814/diacritica.406

Butt, M. (2010). The light verb jungle: Still hacking away. In M. Amberber, B. Baker, & M. Harvey (Eds.), Complex predicates: Cross-linguistic perspectives on event structure (pp. 48–78). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511712234.004

Chierchia, G. (1998a). Plurality of mass nouns and the notion of ‘semantic parameter’. In S. Rothstein (Ed.), Events and grammar (pp. 53–103). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-3969-4_4

Chierchia, G. (1998b). Reference to kinds across language. Natural language semantics, 6(4), 339–405. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008324218506

Chierchia, G. (2010). Mass nouns, vagueness and semantic variation. Synthese, 174(1), 99–149. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-009-9686-6

Comrie, B. (1976). Aspect: An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doetjes, J. S. (1997). Quantifiers and selection. On the distribution of quantifying expressions in French, Dutch and English. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics.

Dowty, D. (1979). Word meaning and Montague grammar: The semantics of verbs and times in generative semantics and in Montague’s PTQ. Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-9473-7

Ferreira, M. (2010). The morpho-semantics of number in Brazilian Portuguese bare singulars. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 9(1), 95–116. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.112

Gillon, B. S. (1992). Towards a common semantics for English count and mass nouns. Linguistics and Philosophy, 15(6), 597–639. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00628112

Grimm, S. (2012). Abstract nouns and countability. Talk presented at Linguistic Society of America Annual Meeting. Portland, OR. January 7, 2012.

Grimm, S. (2014). Individuating the abstract. In U. Etxeberria, A. Fălăuş, A. Irurtzun, & B. Leferman (Eds.), Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 18, University of the Basque Country, Vitoria, Spain, 182–200.

Grimm, S. (2016). Crime investigations: The countability profile of a delinquent noun. Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication, 11, 1–26. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4148/1944-3676.1111

Grimm, S., & Levin, B. (2012). Who Has More Furniture? An Exploration of the Bases for Comparison. Presentation at the Mass/Count in Linguistics, Philosophy and Cognitive Science Conference, École Normale Supérieure, Paris, France, December, 2012.

Katalin, K. (2011). Remarks on semelfactive verbs in English and Hungarian. Argumentum, 7, 121–128.

Li, P., Dunham, Y., & Carey, S. (2009). Of substance: The nature of language effects on entity construal. Cognitive Psychology, 58(4), 487–524. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2008.12.001

Lima, S. (2015). Quantity judgments in bilingual speakers (Yudja/Brazilian Portuguese). Letras de Hoje, 50(1), 84–90. DOI: http://doi.org/10.15448/1984-7726.2015.1.18389

Lima, S. (2019). Processing coercion in Brazilian Portuguese: Grinding objects and packaging substances. In K. Carlson, C.Clifton, Jr., & J. D. Fodor (Eds.), Grammatical Approaches to Language Processing (pp. 209–224). Cham: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01563-3_11

Lima, S. O., & Gomes, A. P. Q. (2016). The interpretation of Brazilian Portuguese bare singulars in neutral contexts. Revista Letras, 93, 193–209. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5380/rel.v93i1.42690

Lima, S., & Oliveira, C. (In press.) Value and quantity in the evaluation of bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese: A priming study. In Proceedings of 48th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages.

Link, G. (1983). The logical analysis of plurals and mass terms: A lattice-theoretical approach. In R. Bäuerle, C. Schwarze, & A. von Stechow (Eds.), Meaning, Use, and Interpretation of Language (pp. 302–323). Berlin; New York: de Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110852820.302

MacNamara, J. (1972). Cognitive basis of language learning in infants. Psychological Review, 79(1), 1–13. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1037/h0031901

MacNamara, J. (1982). Names for things: A study of human learning. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Menuzzi, S. de M., Silva, M. C. F., & Doetjes, J. (2015). Subject bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese and information structure. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 14(1), 7–44. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.56

Müller, A. (2002). The semantics of generic quantification in Brazilian Portuguese. Probus, 14(2), 279–298. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/prbs.2002.011

Müller, A., & Oliveira, F. (2004). Bare nominals and number in Brazilian and European Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 3(1), 9–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.17

Munn, A., & Schmitt, C. (2005). Number and indefinites. Lingua, 115(6), 821–855. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2004.01.007

Paraguassu-Martins, N., & Müller, A. (2007). A distinção contável-massivo nas línguas naturais [The count-mass distinction in natural languages]. Revista Letras, 73, 169–183. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5380/rel.v73i0.7544

Pelletier, F. J. (1975). Non-singular reference: Some preliminaries. Philosophia, 5(4), 451–465. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/BF02379268

Pires de Oliveira, R. (2014). Dobras e redobras: Do singular nu no Português Brasileiro: Costurando a semântica entre as línguas [Folds and redoubles: On bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese: Sewing the semantics among the languages]. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS.

Pires de Oliveira, R., & de Swart, H. (2015). Brazilian Portuguese noun phrases: An optimality theoretic perspective. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 14(1), 63–93. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jpl.58

Pires de Oliveira, R., & Rothstein, S. (2011a). Two sorts of bare nouns in Brazilian Portuguese. Revista da ABRALIN, 10(3), 231–266. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5380/rabl.v10i3.32352

Pires de Oliveira, R., & Rothstein, S. (2011b). Bare singular noun phrases are mass in Brazilian Portuguese. Lingua, 121(15), 2153–2175. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2011.09.004

Resende, M. S. (2016). A qualidade massa/contável dos nomes deverbais. Raído, 10(24), 192–202.

Rothstein, S. (1999). Fine-grained structure in the eventuality domain: The semantics of predicative adjective phrases and be. Natural Language Semantics, 7(4), 347–420. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008397810024

Rothstein, S. (2004). Structuring events: A Study in the semantics of lexical aspect. Oxford: Blackwell. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/9780470759127

Rothstein, S. (2010). Counting and the mass/count distinction. Journal of Semantics, 27(3), 343–397. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffq007

Samuelson, L. K., & Schiffer, R. N. (2011). Statistics and the shape bias: It matters what statistics you get and when you get them. Manuscript.

Santana, R. S., & Grolla, E. (2018). A aceitabilidade do singular nu pré-verbal em Português Brasileiro [The acceptability of pre-verbal bare singulars in Brazilian Portuguese]. Revista Linguíʃtica, 14(2), 194–214. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31513/linguistica.2018.v14n2a17532

Scher, A. P. (2004). As constru̧ões com o verbo leve “dar” e as nominaliza̧ões em –ada no Português do Brasil [The constructions with the light verb ‘give’ and the nominalizations in –ada in Brazilian Portuguese]. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, SP.

Schmitt, C. (1996). Aspect and the syntax of noun phrases. PhD dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park.

Schmitt, C., & Kester, E. (2005). Bare nominals in Papiamentu and Brazilian Portuguese: An exo-skeletal approach. In R. S. Gess, & E. J. Rubin (Eds.), Theoretical and Experimental Approaches to Romance Linguistics: Selected papers from the 34th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL) (pp. 237–256). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.272.15sch

Schmitt, C., & Munn, A. (1999). Against the nominal mapping parameter: Bare nouns in Brazilian Portuguese. In P. Tamanji, M. Hirotani, & N. Hall (Eds.), Proceedings of North Eastern Linguistic Society 29 (NELS) (pp. 339–354). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Schmitt, C., & Munn, A. (2002). The syntax and semantics of bare arguments in Brazilian Portuguese. Linguistic Variation Yearbook, 2(1), 185–216. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/livy.2.08sch

Smith, C. (1997). The parameter of aspect (2nd ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-5606-6

Vendler, Z. (1967). Linguistics in philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.